I first experienced Eli Pariser’s fabled filter bubble twenty years ago, before scrolling the fevered feeds of social media had such a hold on us. I didn’t have a television, but my ex-girlfriend had one stored in our garage. I pulled it out specifically to watch the 2004 election coverage on the news. George W. Bush was up for reelection against challenger John Kerry. For the two years leading up to this election, I had been in graduate school in San Diego. So, no, I didn’t know anyone who liked Bush, no one who didn’t make fun of him, not a single person who had nice things to say. To be fair, I didn’t really know anyone who liked Kerry either, but…

I sat there, by myself, in front of that small cathode-ray television tube, wondering what the hell I was seeing. How could this many people be voting for the guy I was sure didn’t have a single fan on the continent?

That’s what it looks like when your bubble bursts, and you’re exposed to the cold light of consensus reality. That’s when you realize you were duped, but by whom?

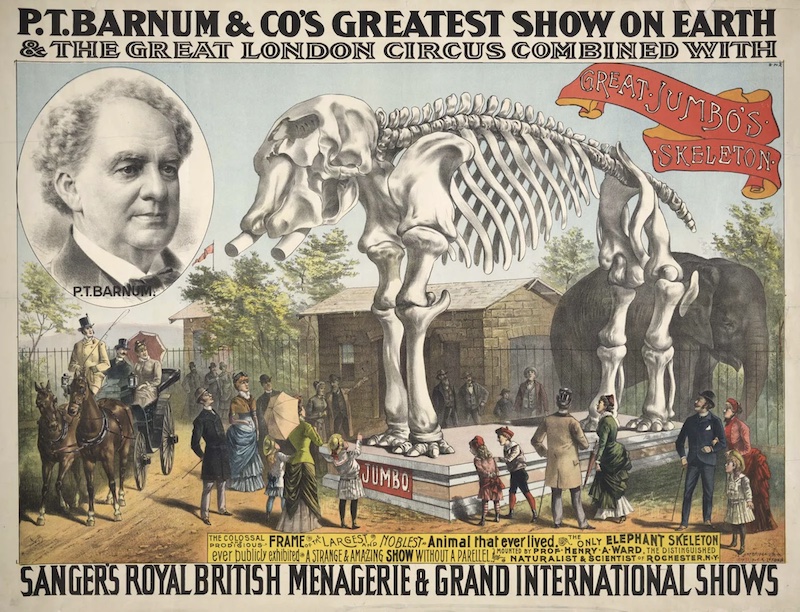

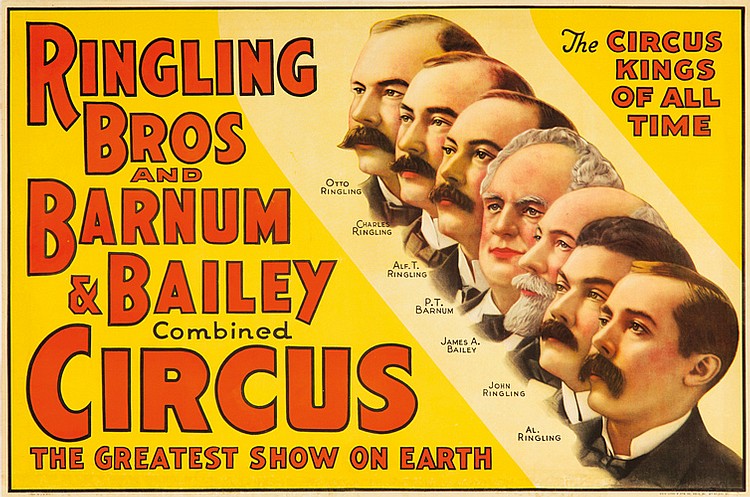

One of the first non-children books I read was a biography of P. T. Barnum. My middle-school mind was fascinated by his brash persona and his blatant sloganeering. “There’s a sucker born every minute,” he supposedly once said as he curated freak shows and curiosities and co-created the Barnum and Bailey Circus, “The Greatest Show on Earth.” Thankfully as a young impressionable mind, I didn’t internalize his con-man values. Maybe if I had, I wouldn’t need side jobs.

But the silver lining isn’t cynicism, nor are koans like that lost on the tricksters and trolls gatekeeping the path. Everybody knows everything yet fails to notice how far they have left to go and how little air they have left to breathe. That’s one of the defining features of a bubble: It’s sealed. Airtight.

“One of the saddest lessons of history is this: If we’ve been bamboozled long enough, we tend to reject any evidence of the bamboozle. We’re no longer interested in finding out the truth. The bamboozle has captured us. It’s simply too painful to acknowledge, even to ourselves, that we’ve been taken.” ― Carl Sagan, The Demon-Haunted World

But we don’t need the internet to be blind to the blight around us, stuck not seeing the things about the world we find too disturbing to know, too annoying to think about, or just plain too inconvenient to consider. We do a lot of it on our own. We all wander through the world with blurry lenses, what the literary theorist Kenneth Burke called “terministic screens.” Have you ever learned a new word and then started seeing it everywhere? Burke would say that it was always there, but you were filtering it out, obscuring it with ignorance. Once it became a part of your terministic screen, then you started seeing it.

Outside the circus, Barnum’s resonant ideas rang much louder than simply hawking curiosities for cash. He served two terms as a Republican in the Connecticut legislature, as well as serving as mayor of Bridgeport, Connecticut. Arguing for the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, the abolitionist Barnum said, “A human soul, ‘that God has created and Christ died for,’ is not to be trifled with. It may tenant the body of a Chinaman, a Turk, an Arab, or a Hottentot—it is still an immortal spirit.” In spite of his outdated nomenclature, the man most known as a 19th-century huckster had more progressive ideas than many of the current lot.

Now the terministic screens are actual screens, shiny rectangles, radiant with outrage. Now the most lucrative approach to news is anything that foments fear, anger, and resentment: any reaction is great, but rage is preferred and more profitable. Now the bubbles are smaller, stronger, and finding one’s way out is a lot more difficult. Any semblance of distortion your reality may have been teasing you with, easing your mind with a blur on the lens, a national election will quickly clear up for you. Your brain left broken, your shelter shattered.