My favorite Talking Head, David Byrne, turns an entire old building in New York City into a giant sound machine in an installation called “Playing the Building.” Xeni Jardin takes a tour. Continue reading “David Byrne’s “Playing the Building” on BBTV”

Cadence Weapon: Check the Technique

I am hereby requesting a bandwagon late-pass. Out of nowhere a few months ago, someone sent me the video for “Sharks” by Cadence Weapon (embedded below). Like many who’ve heard the track, I was instantly hooked, and started looking for more. Well, lucky me, Cadence Weapon had just put out a new disc of his glitchy Hip-hop called Afterparty Babies (Anti, 2008). It’s been in or near the top of the playlist ever since.

I’ve been down since thirteen literally, bombing the whole system up, beautifying the scenery. — Big Juss, Company Flow

Before dropping the bubbly beats and fresh rhymes, Cadence Weapon a.k.a. Rollie Pemberton used to write reviews for a major music website, but way before that, his dad was Edmonton, Alberta’s premiere source for Hip-hop. At age thirteen, Rollie knew he wanted to rap, and his starting young is evident in the work: His records — though he’s only been making them for a few years — are those of a veteran. He’s grown up with this ish. It’s in his bloodstream.

Clever and catchy Hip-hop that doesn’t outsmart itself might be more prevalent now than ever, but it still isn’t lurking on every airwave. I’m glad to pass the name Cadence Weapon on to you. He gets respect for the rep when he speaks. Check the technique and see if you can follow it.

Roy Christopher: Tell me about the new record. What’s different this time around?

Cadence Weapon: This record is faster paced, more cohesive and tied to a connecting concept. It’s more personal and drawing from more dancefloor influences than IDM or grime.

Cadence Weapon: This record is faster paced, more cohesive and tied to a connecting concept. It’s more personal and drawing from more dancefloor influences than IDM or grime.

RC: Your dad was a Hip-hop pioneer up there in Edmonton. What are your earliest impressions of Hip-hop and music?

CW: I grew up on rap music and culture so I just saw it as normal. Predictably, I was isolated not knowing many other people who were into rap music so it was just something I liked myself. I saw it as an extension of poetry or any other artistic expression, and I still do.

RC: Though Hip-hop as a genre is often innovative and rebellious, it’s also steeped in strict traditions and rules. What’s your take on this contradiction — and negotiating it as an artist?

CW: It’s one of the strangest things about the music. It’s the most open-ended genre in terms of possibilities. You can sample someone walking down the street and rap about your mom’s hat if you wanted to, because there are no constraints in rap, just the ones built by the individual. The regimented nature of rap is a response to its corporate status: People thinking you have to maintain the status quo to retain sales. It’s shitty.

RC: Comedian David Spade once said that acts spend the first part of their career looking for a hook and the rest of it trying to bury that hook. To me, this is analogous to one having a “hit” (e.g., De La Soul’s “Me, Myself, and I,” or more recently, Aesop Rock‘s “No Regrets”) Do you ever resent the attention you got from “Sharks”?

CW: The success of “Sharks” doesn’t bother me. As with any single, it’s seen as representative of who I was at the time of its release. It’s a catchy song, it’s youthful and aggressive and not necessarily who I am right now, but I accept it as a period in my life. I am not trying to get rid of the memory of that song, I feel like there are still layers to it that people haven’t necessarily uncovered.

RC: What’s next for Rollie Pemberton? And for Cadence Weapon?

CW: Next for Rollie Pemberton: making the most of my free time, playing basketball, getting back into party mode, bettering myself.

Next for Cadence Weapon: actually collaborating with people on my next album, writing about death and body image and the other side of the world, starting a band, rapping harder.

———-

Here’s the video that launched the fandom, “Sharks” from Cadence Weapon’s debut record, Breaking Kayfabe (Upper Class, 2005) (runtime :4:22):

The Irony of the Archive

My parents have been living in their current house for over twenty years. My Moms’ part is a stockpile of paints, fabrics, and other craft supplies. Dad tends to save anything that he thinks might be useful later. Their combined efforts have amassed an archive that escapes any scheme of organization. I’ve overheard both mention recently that they had to go buy something that they knew they already had because they couldn’t find it among the clutter. Continue reading “The Irony of the Archive”

My parents have been living in their current house for over twenty years. My Moms’ part is a stockpile of paints, fabrics, and other craft supplies. Dad tends to save anything that he thinks might be useful later. Their combined efforts have amassed an archive that escapes any scheme of organization. I’ve overheard both mention recently that they had to go buy something that they knew they already had because they couldn’t find it among the clutter. Continue reading “The Irony of the Archive”

Recurring Themes, Part Seven: Categorical Contempt for Others

During a stint at a record store a couple of years ago, I had a lady come in looking for the new Neil Diamond record. As I located the CD for her, she started talking down to me, as if I had no knowledge of Neil Diamond’s history. Sure, part of this was because she thought I was younger than I was (no one expects a mid-thirties sales clerk with a master’s degree in a South Alabama record store), but part of it was indicative of a widespread elitism, a largely misplaced but ubiquitous contempt for others. Continue reading “Recurring Themes, Part Seven: Categorical Contempt for Others”

R.I.P. Camu Tao

The world lost a true talent last Sunday. Tero “Camu Tao” Smith had lyrical skills and a spirit that seldom comes around. He was consistently dope and relentlessly fun. My thoughts are with his family, his friends, and his many fans. Continue reading “R.I.P. Camu Tao”

A New Notebook: Three More Giant Influences

I made a “Master Cluster” notebook. Check it out.

Continue reading “A New Notebook: Three More Giant Influences”

Rest in Peace: Three Giant Influences

Not normally one to dwell on such things, I thought it would be appropriate to acknowledge a few recent deaths, as the lives of these people impacted mine in profound ways. Continue reading “Rest in Peace: Three Giant Influences”

Building a Name: 21st Century Cave Painting

When pressed about his motivation for painting in the documentary Style Wars (1982), graffiti artist Duster explained that the elder writers give you a name and tell you to see how big you can get it. After watching this movie again recently it struck me that branding and advertising are charged with similar motivation and similar challenges. Continue reading “Building a Name: 21st Century Cave Painting”

Shelflife: The Future of Books

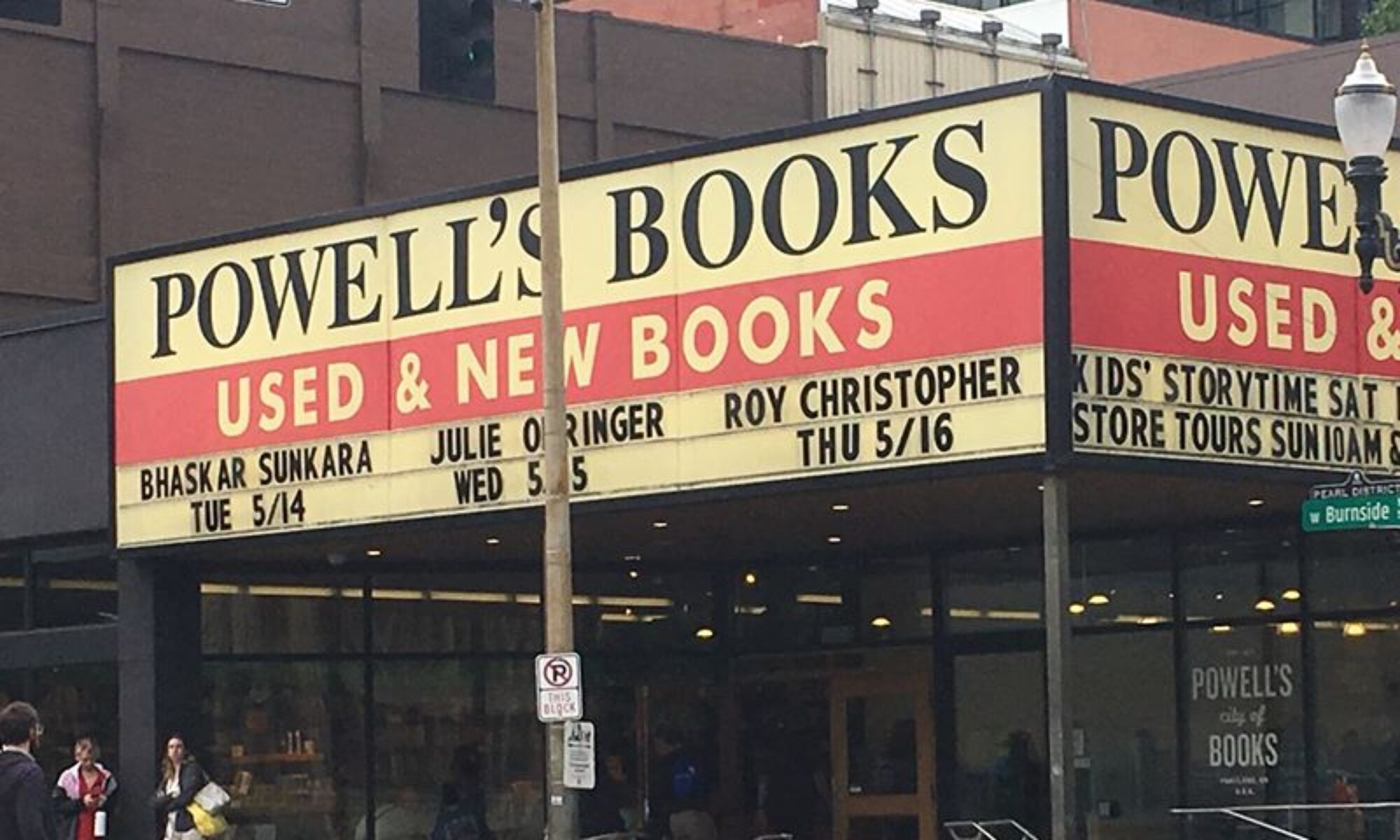

The other day, Soft Skull‘s Richard Nash posted a link to a speech by Mike Shatzkin on the future of books and booksellers, calling it “dead-on.” Having heard the doors to traditional book publishing creek as they close, I have to agree with Richard: insights abound. It looks like the Cluetrain has finally reached the dead media…

One of Shatzkin’s main insights concerns the impact of the web on publishing. No, it’s not the old, knee-jerk “end of print” claim, but one that may still point to print’s end. Where the book industry’s organization is arranged around formats (i.e., it is horizontal), the organization of the web lends itself to topics of interest regardless of format (i.e., it is vertical). The file is now the medium of distribution — not the book or the magazine or whatever: The barriers between media dissolve online. He explains it thusly,

…the Internet naturally tends to vertical organization, subject-specific organization. It naturally facilitates clustering around subjects. And as communities and information sources form around specific interests, they undercut the value of what is more general and superficial information within horizontal media. At the same time, format-specialization makes less and less sense. Twentieth century broadcasting, newspapers, and books had special requirements that demanded scale, sometimes related to production but more often driven by the requirements of distribution. On the Internet, distribution is by files, and files can contain material to be read on screen or printed and read; it can contain words or pictures; it can contain audio or video or animation or pieces of art. When the file becomes the medium of exchange, not a book or a newspaper or a magazine or a broadcast delivered over a network with very limited capacity, it eliminates the barriers that kept old media locked in their formats.

The audio files of the music industry are much more suited for the digital revolution of production. That is, the shift from atoms to bits (though there is The Institute for the Future of the Book which hosts projects such as McKenzie Wark‘s G4M3R 7H30RY, Lawrence Lessig’s release of The Future of Ideas free online, and No Starch Press recently offered free torrents of a couple of their titles). Shatzkin argues that audio books, portable readers, and digital print-on-demand will enable the same for books. Even so, we aren’t seeing the total paradigm upheaval in book publishing that we’ve seen in music. Its transformation is happening piecemeal. For the book market, the shift is good for consumers and long-tail-ready retailers, but not so much for old-order publishers.

The audio files of the music industry are much more suited for the digital revolution of production. That is, the shift from atoms to bits (though there is The Institute for the Future of the Book which hosts projects such as McKenzie Wark‘s G4M3R 7H30RY, Lawrence Lessig’s release of The Future of Ideas free online, and No Starch Press recently offered free torrents of a couple of their titles). Shatzkin argues that audio books, portable readers, and digital print-on-demand will enable the same for books. Even so, we aren’t seeing the total paradigm upheaval in book publishing that we’ve seen in music. Its transformation is happening piecemeal. For the book market, the shift is good for consumers and long-tail-ready retailers, but not so much for old-order publishers.

For the smaller publishers, branding is now social. Building community through social sites — as Disinformation and Soft Skull have done — is essential, but it just doesn’t make sense for large legacy publishers like Harper Collins or Random House. These smaller web-age publishers are much more agile and attuned to the times. And, as some older publishers are finding out, having an extensive back catalog does not necessarily mean having viable long-tail content.

For the smaller publishers, branding is now social. Building community through social sites — as Disinformation and Soft Skull have done — is essential, but it just doesn’t make sense for large legacy publishers like Harper Collins or Random House. These smaller web-age publishers are much more agile and attuned to the times. And, as some older publishers are finding out, having an extensive back catalog does not necessarily mean having viable long-tail content.

Competition is stiff and getting stiffer, the zeitgeist is leaving books behind, and the shift to digital is still infecting everything. What does all of this mean for book publishers and authors? As a self-publisher and as a writer, I’ve seen the effects of these trends at work firsthand. Though I opted for a more traditional route with Follow for Now (I’m maintaining an inventory of atoms), print-on-demand services are good and getting better. The digital options are now rivaling the traditional paths to print. This is good news for writers looking for ways to get their ideas out there. The same can be said for the ease of blogging. Making the transition to “paid writer” or “author with a book deal” is the difficult part, though it’s still possible: Christian Lander, the guy who started the “Stuff White People Like” blog, recently landed a reported $300,000 book deal with Random House.

But where is the middle ground? Lander’s deal is clearly an exception to the new rules, and to call the unpaid blogging community “overcrowded” is to do the word a disservice. Can writers — like their musician counterparts — make a living in the new market? Is its resistance to digital assimilation a boon or a burden for book publishing?

Dave Allen: Every Force Evolves a Form

I can’t remember the first time I heard Gang of Four, but I do distinctly remember a lot of things making sense once I did. Their jagged and angular bursts of guitar, funky rhythms, deadpan vocals, and overtly personal-as-political lyrics predated so many other bands I’d been listening to. Dave Allen was the man behind the bass, and now he’s the man behind Pampelmoose, a Portland-based music and media blog. Continue reading “Dave Allen: Every Force Evolves a Form”

I can’t remember the first time I heard Gang of Four, but I do distinctly remember a lot of things making sense once I did. Their jagged and angular bursts of guitar, funky rhythms, deadpan vocals, and overtly personal-as-political lyrics predated so many other bands I’d been listening to. Dave Allen was the man behind the bass, and now he’s the man behind Pampelmoose, a Portland-based music and media blog. Continue reading “Dave Allen: Every Force Evolves a Form”