“How easily we forget how bright the moonlight can be when we spend our nights in the wan glow of artificial light.”

I found the above quotation on page 40 of a book. I don’t know what book. I’m usually more diligent than that about such pertinent details in my notes, but in this case all I have is the quotation and a page number. I’ve done countless searches and asked several librarians, to no avail.

Appropriate, perhaps.

It matters where such quotations were found, and it matters who wrote them—for now. In late 2000, during an especially impoverished period of my adult life, I was going to the Seattle Public Library almost every day. I was reading bits and pieces of so many books. I remember digging deeper into the work of Walter Benjamin, discovering Paul Virilio, and the row of volumes I had lined up against the wall in an almost unfurnished apartment, their spines and call numbers pointed at the ceiling. Due dates and new arrivals kept the books rotating, and at some point, I started having a difficult time keeping up with where I’d read what. So, I started a research journal.

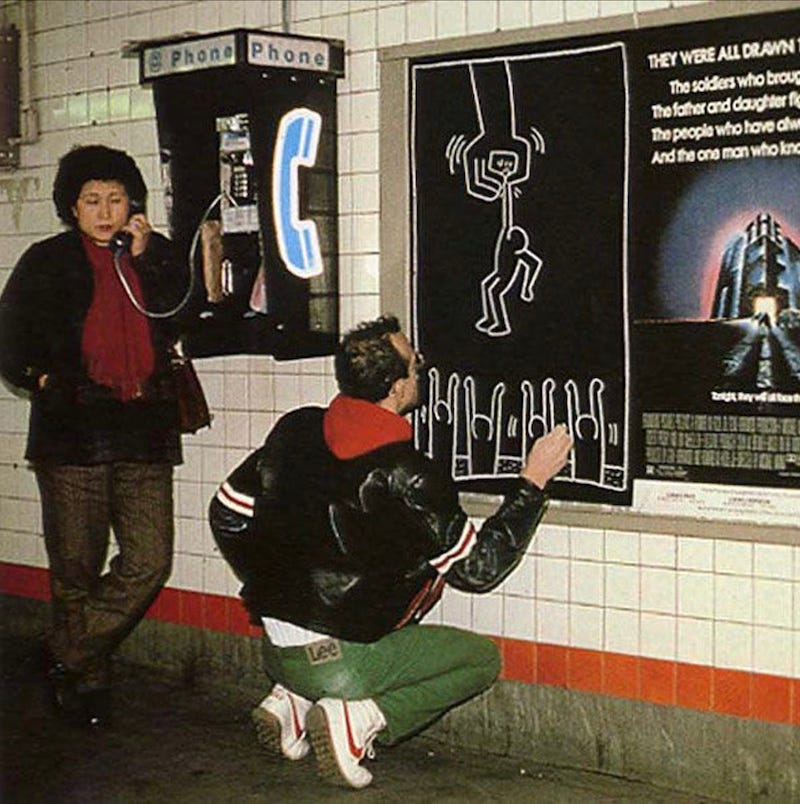

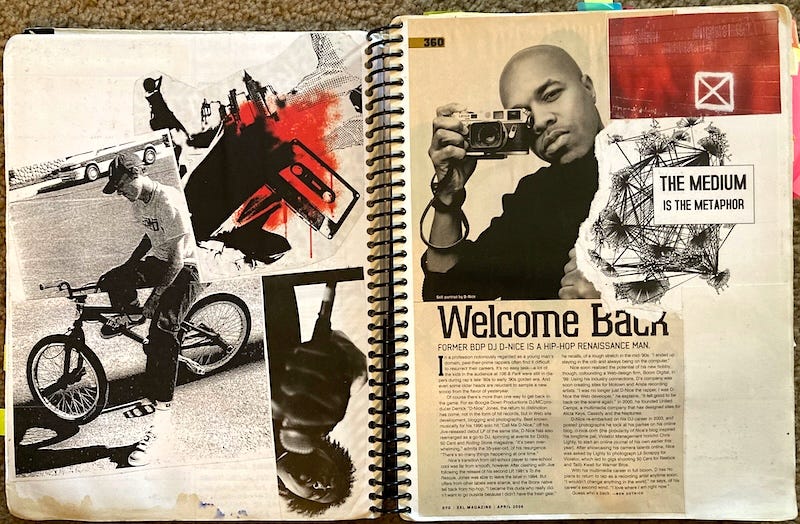

My research journal has always been a sort of commonplace book, an idiosyncratic mix of journal and scrapbook, collecting drawings, diagrams, clips from magazines, lists, and quotes from dreams, friends, films, and books. With the emergence of printed text, its recycling of and relation to other texts were taken as a given. Commonplace books have been used as personal repositories of wit, wisdom, and knowledge at least as far back as the 15th century. As Walter Ong wrote in his 1982 book, Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word,

Manuscript culture had taken intertextuality for granted. Still tied to the commonplace tradition of the old oral world, it deliberately created texts out of other texts, borrowing, adapting, sharing the common, originally oral, formulas and themes, even though it worked them up into fresh literary forms impossible without writing.1

The Enlightenment philosopher John Locke started maintaining a commonplace book in 1652. He wrote an elaborate guide to commonplace books in 1685 in French, and in 1706 it was translated into English as A New Method of Making Common-Place-Books. The writer and NotebookLM cofounder Steven Johnson has compared the commonplace book to the link-laden, hypertextual environment of the internet. Like our digital devices, these books represent what Jonathan Swift once called “supplemental memory.”2 Once we write something down and keep it, we no longer have to actively remember it.

“We read to inherit the words, but something is always between us and the words.” — Victoria Chang, “Language,” Obit

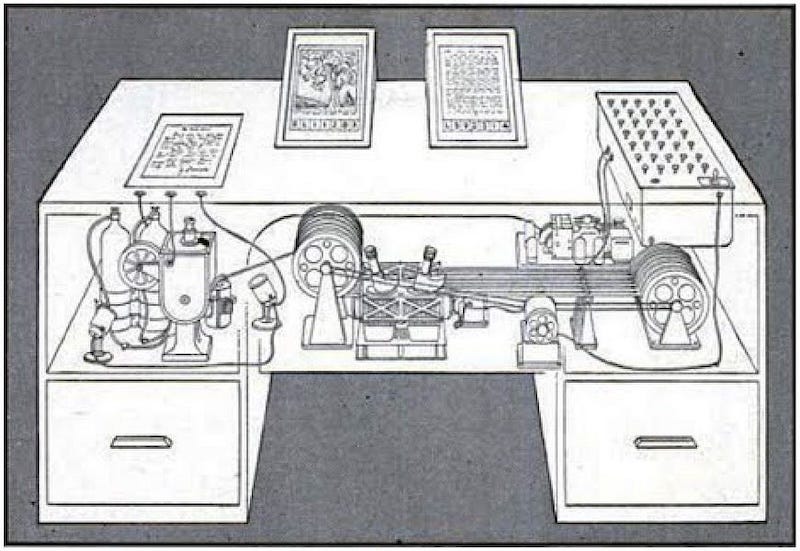

Proposed in his 1945 article “As We May Think” published in The Atlantic, Vannevar Bush’s memex (itself a portmanteau of “memory” and “expansion”) was a kind of proto-personal computer, expanding the commonplace idea to a desk-bound apparatus for research. The memex was a dream machine for navigating and researching with the vast stores of information of the time using cameras, microfilm, and print—an annotated analog hypertext system. Bush wrote, “Wholly new forms of encyclopedias will appear, ready-made with a mesh of associative trails running through them, ready to be dropped into the memex and there amplified.”3 Though commonplace books and Paul Otlet’s 1934 Traité de Documentation prefigured Bush’s memex and its “associative trails,” it is a closer analog to our current personal archiving devices (e.g., cloud-storage services, smartphone-camera rolls, social-media posts, and blogs), “a sort of mechanized private file and library,” as he put it.4 We all have just such an archive in our pockets now.

“The fields are cultivated by horse-ploughs while books are written by machinery.” — from George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four

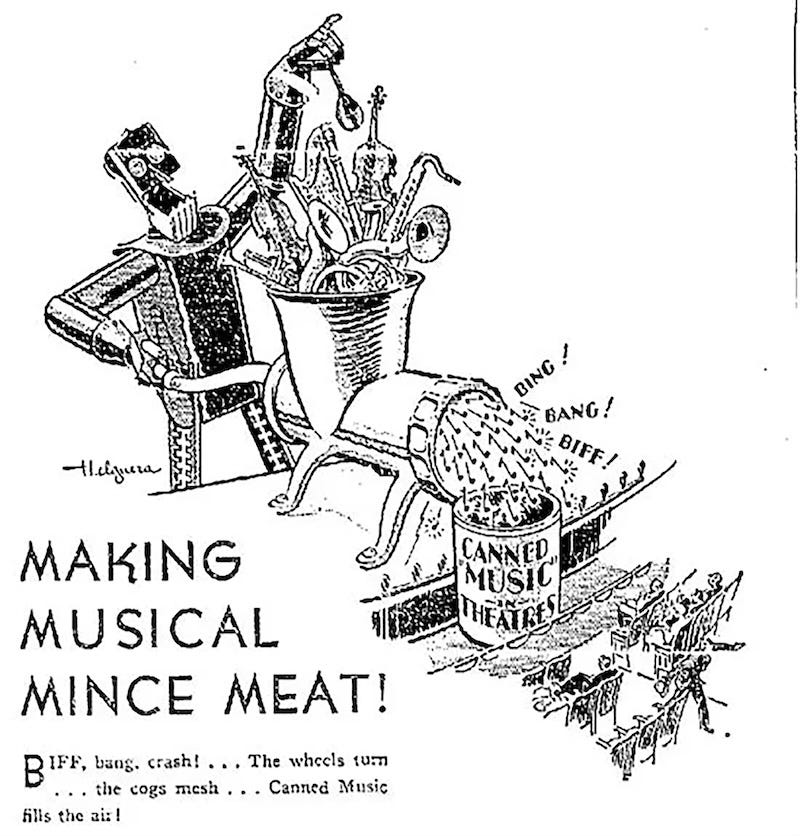

As we saw happen to music: As soon as music was replicated as digital information seared onto compact discs, MP3s, peer-to-peer trading, and streaming were inevitable as bandwidth increased to accommodate them. As soon as sampling went digital, music was poised to be parsed into smaller and smaller reassemblable bits, and we’ve taken full advantage of its malleability. As the historian Carla Nappi told me in 2019,

Several years ago, I took a digital DJing course and my first baby steps in learning the craft. I was immediately struck by how similar the art of a DJ was, at least as I was learning and experiencing it, to that of a historian. We amass archives, we tell stories that have a kind of narrative arc, we work with time as a material. Sampling is a kind of quotation. Distortion and other effects are ways of reading a musical text. There are just so many resonances, and I felt that thinking about these crafts together could be a way of informing and inspiring both of them.5

The most original DJ is still playing pieces of other people’s past songs. The most original writer is still using the same linguistic tools to reassemble pieces of the past into a form resembling something new.

“Thou shall not make a machine in the likeness of a human mind.” — Rayna Butler, Orange Catholic Bible (from Frank Herbert’s Dune)

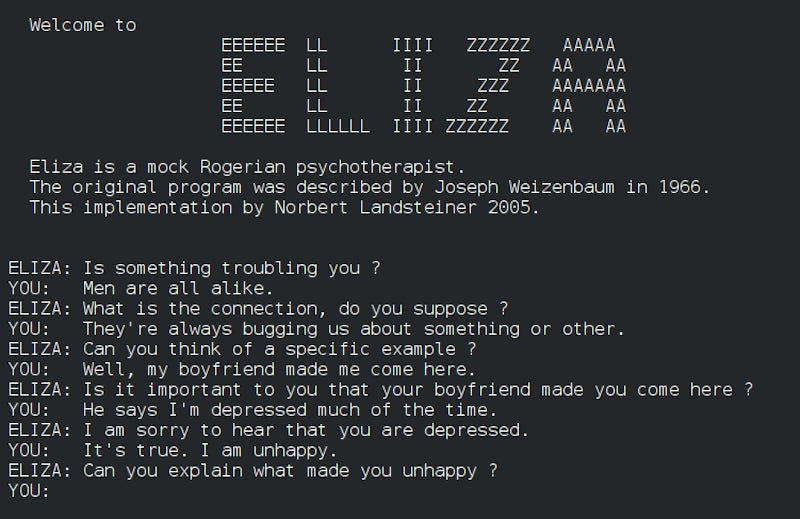

The cognitive scientist Douglas Hofstadter writes of what’s been called the ELIZA effect, after Joseph Weizenbaum’s 1966 therapist chatbot ELIZA, “the most superficial of syntactic tricks convinced some people who interacted with ELIZA that the program actually understood everything that they were saying, sympathized with them, even empathized with them.” Warren Ellis once observed, “If you believe that your thoughts originate inside your brain, do you also believe that television shows are made inside your television set?” You don’t believe that the DJ is playing any of the instruments they sample, so why do you believe the AI is thinking or comprehending any of its responses? It’s a version of the ELIZA effect, but much bigger, deeper, all-encompassing, and disturbing.

As soon as word processing was available, providing the literary fodder for machines, chatbots and large language models were not far to follow. In his book Language Machines, Leif Weatherby writes,“Language models capture language as a cultural system, not as intelligence.”6 That’s a crucial distinction. What passes for AI these days can compose a poem, summarize a novel, or draft an email, but it doesn’t know why. The why is the whole thing. At the risk of oversimplifying a very complex situation, the why is the intelligence. We’ve been steadily removing the human—what Weatherby calls “remainder humanity”—from creative processes, offloading and outsourcing more and more of them to machines and computers. That’s fine, but we’re devaluing, defunding, or demonetizing a lot of the fun part(s).

“It’s much harder to neglect words when they are coming out of your mouth.” — Owen King, The New Yorker

What happens when writing is just prompting? When a library is just a giant generative machine that turns texts into another medium of your choice? Just as musicians became “recording artists,” writers will become something else, perhaps “prompt engineers,” until the machines no longer need prompts, until they no longer need human input at all. Until the wan glow of their artificial light is all the light that’s left.

“I’m just sitting here

Watching the past dim

And the future disappear.”

— WNGWLKR

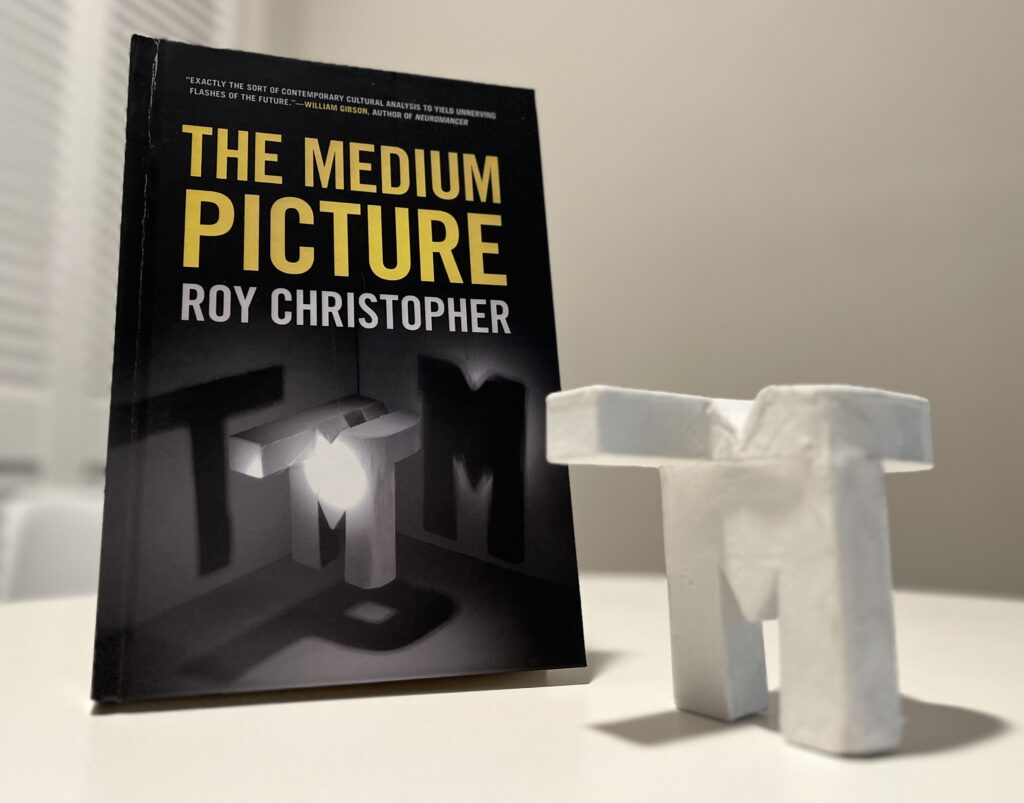

Though I don’t mention allusions anywhere in it, this piece is a rough extension of the research for my book The Grand Allusion. If anyone has any ideas about who might publish it, let me know.

NOTES:

1 Walter J. Ong, Orality and Literacy, New York: Routledge, 1982, 131.

2 Quoted in Sam Dolbear, “John Locke’s Method for Common-Place Books,” Public Domain Review, May 8, 2019.

3 Vannevar Bush, “As We May Think,” The Atlantic Monthly, Vol. 176, no. 1., July, 1945, pp. 101–8.

4 Ibid.

5 Quoted in Roy Christopher, “Carla Nappi: Historical Friction,” in Roy Christopher (ed.), Follow for Now, Vol. 2: More Interviews With Friends and Heroes (pp. 21-32), punctum books, 2021, 29.

6 Leif Weatherby, Language Machines: Cultural AI and the end of Remainder Humanism, Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2025, 5.