Of all the technologies we take for granted, electricity has to be near the top of the list. Though it shouldn’t ever be interrupted, we’re not that suprised when the wifi is down. Streaming services still regularly buffer. Pinwheels, hourglasses, ellipses—an entire semiotics of technology’s foibles, failures, and inconveniences. But when the power goes out, everything stops. Everything. And even though they’re not that uncommon, we’re not prepared. As the former broadcast journalist Ted Koppel puts in his 2015 book Lights Out: A Cyberattack, A Nation Unprepared, Surviving the Aftermath, “We tend to come up with funding after disaster strikes.”

With historical contrast, in his 2010 book, When the Lights Went Out: A History of Blackouts in America, the technologist David E. Nye writes that “by 1965, many New Yorkers regarded a blackout as a violation of the expected order of things. Yet it seemed an anomaly without long-term implications, and the paralysis of that night became the occasion for a liminal moment.” Such liminal moments are hard to come by, as the machinations of the city regularly work against the freedom they afford. Increasingly, the spaces required for dreaming, for creation, and indeed for freedom, are the product of artifice. They have to be intentionally assembled and deployed. Kodwo Eshun writes,

The technological conditions for intervention in the present have to be artificially constructed. They are not spontaneously available. To embark on a project that is set in the present, you have to renounce digital abundance by undergoing a temporal diet or media famine. You have to turn yourself into a castaway marooned on an island of the present separated from the abundance of digital archives and previous musical eras that continually saturate the contemporary.1

The idea of an outside or in-between space of dreaming recalls Hakim Bey’s temporary autonomous zone (TAZ). That is, the creation of temporary spaces that allow for moments of freedom, acts of creativity, and the availability of otherwise nonexistent autonomy outside the reach of established authority. Though certainly not the same thing, these spaces are similar to William Gibson’s idea of bohemias: subcultural backwaters that allow for new forms to flourish outside the influence of hegemony (Gibson cites Haight-Ashbury in the 1960s and Seattle in the 1990s as examples). Co-opted and all but defanged by the rave culture that followed its inception in 1991, the TAZ deserves a reassessment in our post-globalized world.

One can imagine assembling one of Bey’s pirate utopias, but it’s easier to see them happening unintentionally. That is, when the mechanizations of modernism break down, leaving us alone in the moment, in an unintentional TAZ. The unintentional TAZ’s most recognizable form might be the blackout: a sudden inescapable shadow of spontaneity and creation.

Writing about a power blackout that affected 50 million people in North America in 2003, Jane Bennett defines assemblages as follows:

Assemblages are ad hoc groupings of diverse elements, of vibrant materials of all sorts. Assemblages are living. throbbing confederations that are able to function despite the persistent presence of energies that confound them from within. They have uneven topographies, because some of the points at which the various affects and bodies cross paths are more heavily trafficked than others. and so power is not distributed equally across its surface. Assemblages are not governed by any central head: no one materiality or type of material has sufficient competence to determine consistently the trajectory or impact of the group. The effects generated by an assemblage are, rather, emergent properties, emergent in that their ability to make something happen (a newly inflected materialism, a blackout, a hurricane, a war on terror) is distinct from the sum of the vital force of each materiality considered alone.2

Admittedly borrowing from Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari (A Thousand Plateaus), as well as Baruch Spinoza (Ethics), Bennett’s assemblage doesn’t lack intention. It lacks human intention. The blackout as monster, overtaking the city in a lumbering lack of light.

“I think bohemians are the subconscious of industrial society. Bohemians are like industrial society, dreaming.” — William Gibson

David E. Nye argues that public space transformed by New York blackouts is not an instance of technological determinism, a topic Nye has explored in depth previously.3 His take seems to flip one of Gibson’s well-worn aphorisms: The street finds its own use for things. If the technological use is culturally determined, then the use finds its own street for things. Nye writes,

By the beginning of the twenty-first century, blackouts were recognized as more than merely latent possibilities. They were unpredictable, but seemed certain to come. Breaks in the continuity of time and space, they opened up contradictory possibilities. From their shadows might emerge a unified communitas or a riot. The blackout shifted its meanings, and achieved new definitions with each repetition. For some, it remained a postmodern form of carnival, where they celebrated an enforced cessation of the city’s vast machinery.4

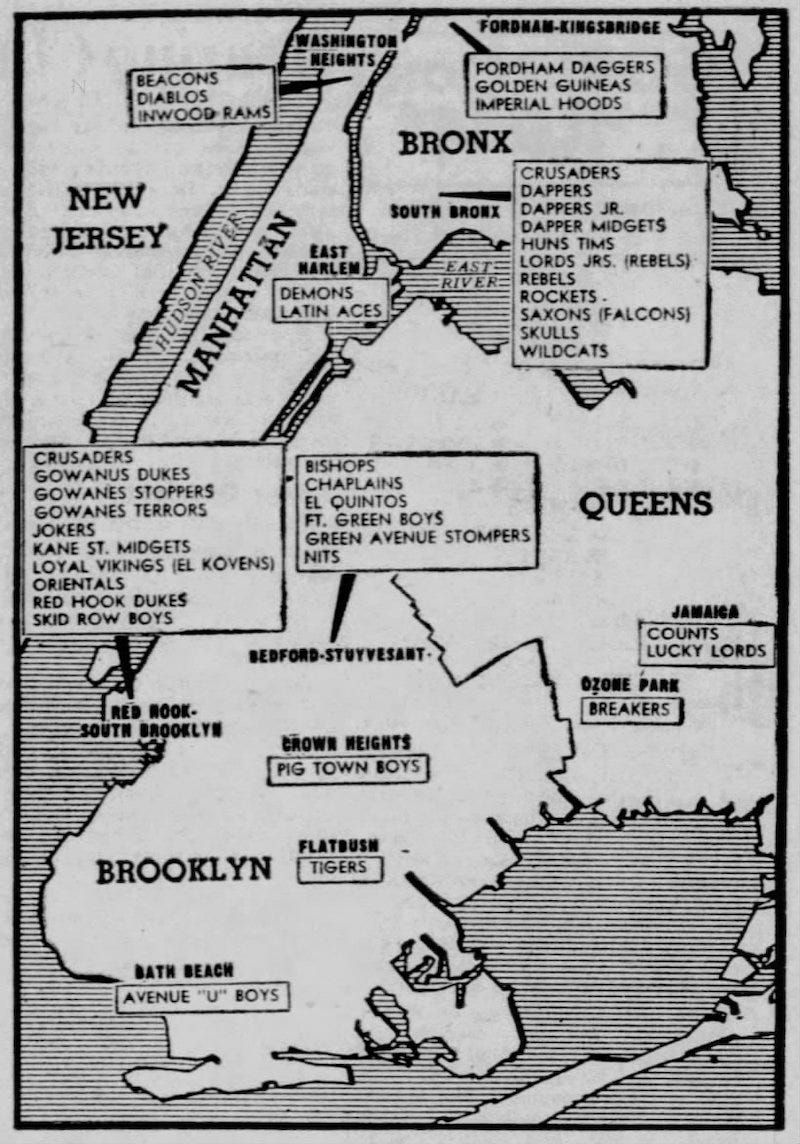

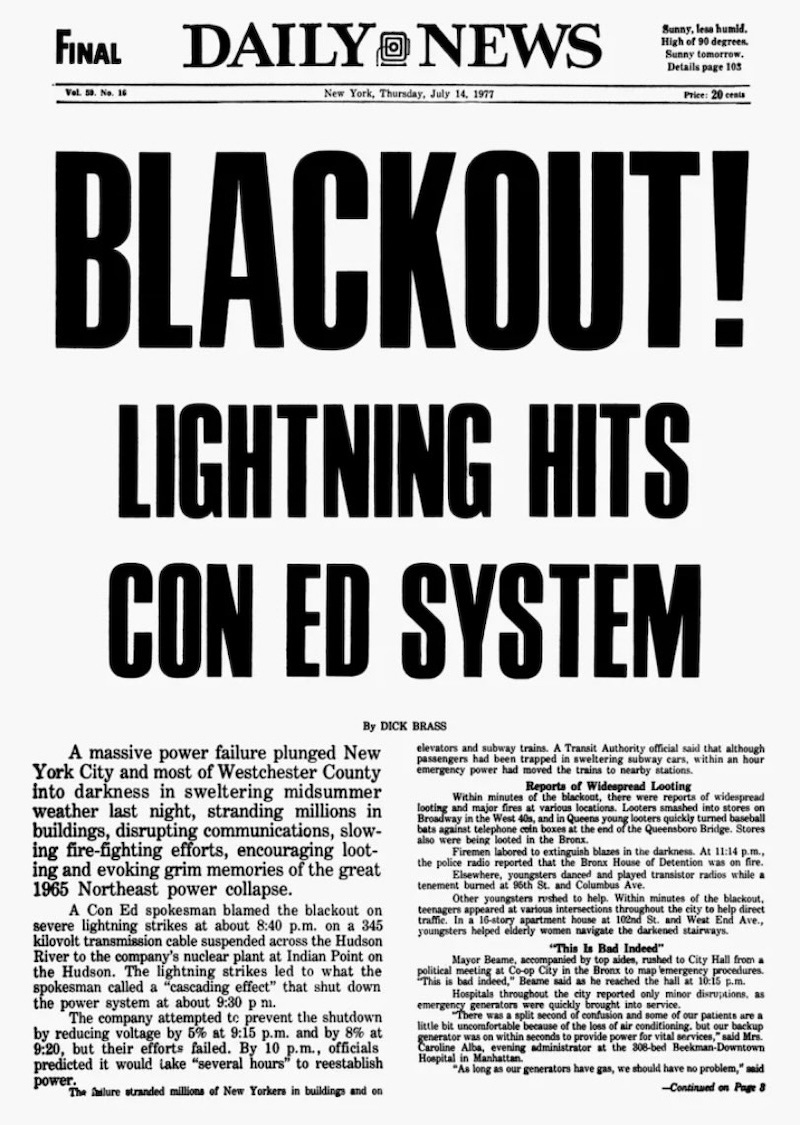

Echoing the massive 1965 blackout, after an 11-day heat wave, on the evening of July 13, 1977, successive lightning strikes strained New York City’s already overtaxed power grid, shutting it down for 24 hours. A blacked-out bohemia pushed the already simmering hip-hop subculture to an overnight boil. Emcee Rahiem of Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five says, “The blackout of 1977 is what helped to spawn a multitude of aspiring hip-hop practitioners, because prior to that, the majority of aspiring DJs didn’t have two turntables and a mixer or the speakers. So, when the blackout happened, it just seems that everybody got the same idea at the same time. And when the lights came back on in New York City, everybody had DJ equipment.” Latin Quarter club manager Paradise Gray adds, “Not too many people in the Bronx could afford big sound systems until after the blackout. Then, everybody had sound.” To retrofit an idea, the Boogie Down became an unintentional temporary autonomous zone that night.

“When you get to the blackout, it shifts hip-hop. It’s a pivotal moment, because like a week later, everybody was a DJ. Everybody.” — MC Debbie D

Easy A.D. of the Cold Crush Brothers sums it up nicely: “The Bronx went from being decayed into something beautiful. The vibration of the music and the combination of bringing all those elements together, you had to be in there to feel it, because most of the time people only experience the music. But when you have all those elements in one place together, then you understand the essence of the hip-hop culture.”5 The blackout didn’t spawn the culture, but the autonomy it afforded pushed it toward national prominence.

This post is part of a loose trilogy:

- Part One: Escape from New York: Hip-Hop 1981

- Part Two: From Blackout to Breakout

- Part Three: Unwavering Radiant: Keith Haring

Notes:

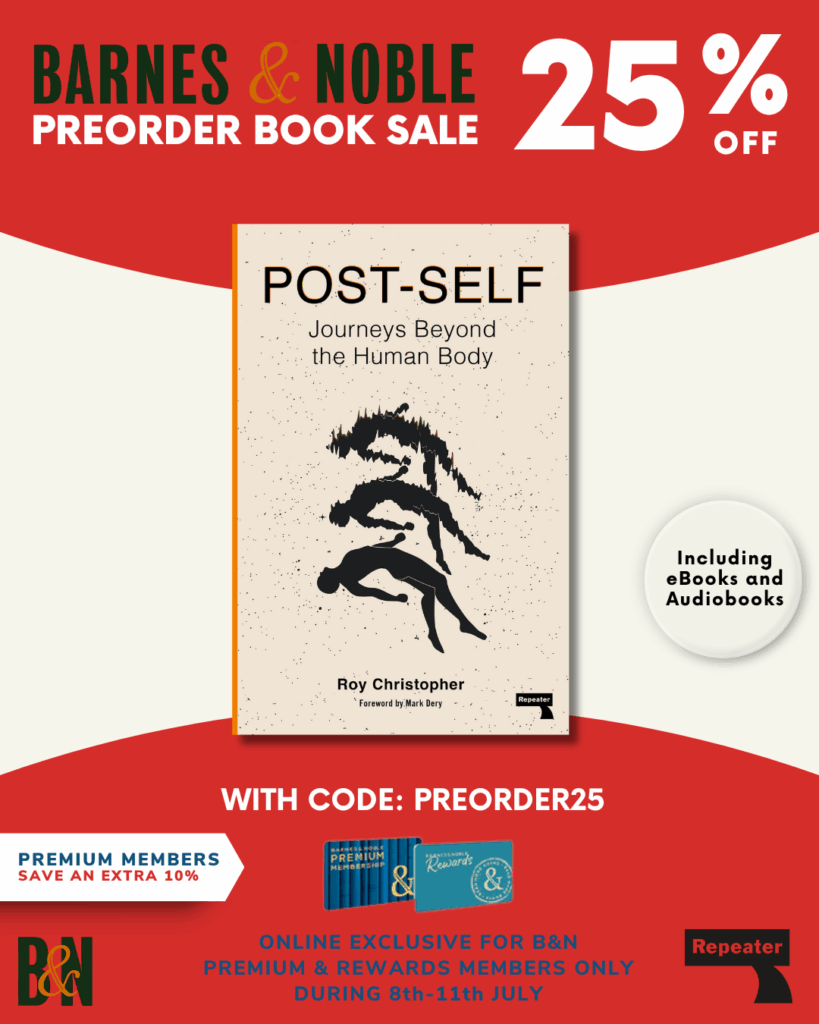

- Quoted in Gavin Butt, Kodwo Eshun, & Mark Fisher (eds.), Post-Punk: Then and Now, London: Repeater Books, 2016, 20; Iain Chambers writes, “With electronic reproduction offering the spectacle of gestures, images, styles, and cultures in a perpetual collage of disintegration and reintegration, the ‘new’ disappears into a permanent present. And with the end of the ‘new’—a concept connected to linearity, to the serial prospects of ‘progress,’ to ‘modernism’— we move into a perpetual recycling of quotations, styles, and fashions: an uninterrupted montage of the ‘now.’”; Iain Chambers, Popular Culture: The Metropolitan Experience, New York: Routledge, 1986, 190.

- Jane Bennett “The Agency of Assemblages and the North American Blackout,” Public Culture ‘7, no. 3 (2005).

- See chapter 2 of David E. Nye, Technology Matters: Questions to Live With, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2006.

- David E. Nye, “Public Space Transformed: New York’s Blackouts,” in Miles Orvell & Jeffrey L. Meikle (eds.), Public Space and the Ideology of Place in American Culture (pp. 367-384), Leiden, NL: Rodopi, 2009, 382.

- These quotations are from Jonathan Abrams’ The Come Up: An Oral History of the Rise of Hip-Hop, New York: Crown, 2022.