If, as Martin Heidegger wrote and Michael Heim clarified, philosophy is to stay one step ahead of science, then art is to stay one step ahead of philosophy. Art has the most freedom as a form of exploration, as a method by which to find the limits of a domain of research. That said, Eugene Thacker doesn’t necessarily consider himself an artist, but, as he told Josephine Bosma in an interview for Net-time, “I have always been interested in approaching things from a theoretical viewpoint, as well as exploring the same issues in, for want of a better term, an artistic domain. Sometimes getting different results, sometimes seeing what you can learn from doing those kind of activities.” Continue reading “Eugene Thacker: Whole Earth DNA”

If, as Martin Heidegger wrote and Michael Heim clarified, philosophy is to stay one step ahead of science, then art is to stay one step ahead of philosophy. Art has the most freedom as a form of exploration, as a method by which to find the limits of a domain of research. That said, Eugene Thacker doesn’t necessarily consider himself an artist, but, as he told Josephine Bosma in an interview for Net-time, “I have always been interested in approaching things from a theoretical viewpoint, as well as exploring the same issues in, for want of a better term, an artistic domain. Sometimes getting different results, sometimes seeing what you can learn from doing those kind of activities.” Continue reading “Eugene Thacker: Whole Earth DNA”

Cage Kennylz: G.R.O.W.N.A.S.S.M.A.N.

Being active in Hip-hop, which is typically thought of as strictly a “youth culture,” doesn’t age well. Growing up is weird enough as it is, but trying to grow up, stay fly, stay true, and stay striving is downright daunting.

Being active in Hip-hop, which is typically thought of as strictly a “youth culture,” doesn’t age well. Growing up is weird enough as it is, but trying to grow up, stay fly, stay true, and stay striving is downright daunting.

Well, Cage Kennylz has grown up in this culture, and unlike those who look silly rocking the mic into their thirties, Cage is growing up and pulling Hip-hop up with him. Continue reading “Cage Kennylz: G.R.O.W.N.A.S.S.M.A.N.”

Lori Damiano: Getting Nowhere Faster

Lori Damiano has been skateboarding and making stuff for so long that I can’t even remember when or where I was first introduced to her work. Somewhere among her involvement in the zine Villa Villa Cola, her animation (she did the menus for the Spike Jones DVD, for one example), and skateboarding like a madwoman, she recently earned a master’s degree in experimental animation from The California Institute of the Arts and helped VVC get the Getting Nowhere Faster DVD out. Continue reading “Lori Damiano: Getting Nowhere Faster”

Lori Damiano has been skateboarding and making stuff for so long that I can’t even remember when or where I was first introduced to her work. Somewhere among her involvement in the zine Villa Villa Cola, her animation (she did the menus for the Spike Jones DVD, for one example), and skateboarding like a madwoman, she recently earned a master’s degree in experimental animation from The California Institute of the Arts and helped VVC get the Getting Nowhere Faster DVD out. Continue reading “Lori Damiano: Getting Nowhere Faster”

Brian Coleman: Nostalgia is Def

“Why the hell didn’t hip-hop albums ever have liner notes?!!??” quoth journalist Brian Coleman, “Hip-hop fans have been robbed of context and background when buying and enjoying classic albums from the Golden Age: the 1980s.” With his self-published book, Rakim Told Me (Waxfacts, 2005), Coleman set out to fix that problem and to fill a void in the written history of hip-hop. That, and where a lot of writers who acknowledge the influence and importance of hip-hop tend to focus on its sociological implications, Coleman stays with the music, how it was made, and where these artists were in the process. He brings a breath of fresh air to the study of hip-hop, just by dint of focusing on the music itself. Continue reading “Brian Coleman: Nostalgia is Def”

“Why the hell didn’t hip-hop albums ever have liner notes?!!??” quoth journalist Brian Coleman, “Hip-hop fans have been robbed of context and background when buying and enjoying classic albums from the Golden Age: the 1980s.” With his self-published book, Rakim Told Me (Waxfacts, 2005), Coleman set out to fix that problem and to fill a void in the written history of hip-hop. That, and where a lot of writers who acknowledge the influence and importance of hip-hop tend to focus on its sociological implications, Coleman stays with the music, how it was made, and where these artists were in the process. He brings a breath of fresh air to the study of hip-hop, just by dint of focusing on the music itself. Continue reading “Brian Coleman: Nostalgia is Def”

DIG BMX Magazine Interview with Roy Christopher

Brian Tunney conducted this interview with me for the impecable DIG BMX Magazine. Here’s an excerpt: “The impetus behind frontwheeldrive.com remains to collect and spread the word about cultural artifacts and the people that make them. I try not to limit the subject matter anymore because I view the mind as an ecology. For any ecology to grow and flourish, it needs diversity. New stuff comes not from the well-defined fields, but from the interaction between them. Allowing theorists, artists, BMXers, musicians, skateboarders, etc. to rub shoulders, frontwheeldrive.com attempts to cross-pollinate areas of interest so that new ideas can grow.”

DIG BMX Magazine

DIG BMX Magazine

The Online World of Roy Christopher

[by Brian Tunney]

Roy Christopher champions a concept he calls ‘Design Science.’ The phrase roughly means the undertaking of the design of one’s own life, and he applies this concept to every facet of his life, including his many undertakings in both print zine making and websites. The basic principle behind Design Science is change. Its stipulation is simple; if you’re not happy with something, change it. And Roy’s made that a universal application within his life, which includes his presence on the Internet. To his credit, he maintains more than a few websites (including frontwheeldrive.com, HEADTUBE, royc.org, 21C, and WHAT ARMY), and also, on occasion, prints a zine called “Headtube,” which he calls “The thinking man’s [sic] BMX magazine.” Though you won’t find the latest tricks, industry gossip or new BMX parts on any of Roy’s sites, you will find a BMX presence. The difference here is that BMX and riding a BMX bike is not portrayed within the microcosm of the BMX world. Roy reaches out to the remainder of the world he comes into contact with, and the result, as he phrases it, “Allows theorists, artists, BMXers, musicians, skateboarders, etc. to rub shoulders… cross-pollinating areas of interest so that new ideas can grow.” Amid pursuing a graduate’s degree, teaching undergrad classes, riding and writing, Roy took the time to answer some questions about his many online endeavors. For more information on all the Design Science of Roy Christopher, visit one of his many websites. And don’t forget that change can be a good thing….

Brian Tunney: How long have you been involved in making zines and or websites for, both BMX and non-related?

Roy Christopher: I started making zines in the summer of 1986. Just after Freestylin’ Magazine did their first big zine report, I went to my friend Matt Bailie’s house and said, “We could do this.” So, in ninth grade, we started writing, shooting photos, and compiling our first issues. The zine was called “The Unexplained” because Matt had always wanted to use that as a name for something (The question mark logo that went along with that zine has since evolved into the WHAT ARMY project). Ten years later, my friend Mark Wieman started messing around with HTML, and I saw the web as another level in zine-making. Though I was still doing print zines, I learned HTML, bought some domain names, and starting building websites.

BT: When did your writing focus begin to drift outside of BMX?

RC: It kinda drifted at first in the early 1990s. The AFA had shut down, the NBL stopped their regional series in the Southeast (I grew up in the South), the magazines and teams disappeared, and it looked like BMX was dead. I was still riding and doing shows, but the death of the contests really put a damper on the energy that BMX had in my creative output. During those dark days of BMX, my writing turned almost completely to music. I finished my undergraduate degree (in Social Science) and moved from Alabama to Seattle. It was there that my zine-making lead to my writing music reviews and features for magazines, but it was there also that I found people to ride with again. So, BMX became a major focus in my zines again by 1995.

BT: What is the impetus behind frontwheeldrive.com, and additionally, your zine HEADTUBE?

RC: “frontwheeldrive” was the name of the zine I was doing when I started making websites, so the first domain name I bought was ‘frontwheeldrive.com’. It took a while for it to find focus, but its current incarnation is a reflection of another personal shift in interests.

Around 1998, I stumbled upon a book by James Gleick called Chaos. It’s a good overview of the disparate areas of research that eventually lead to the field of chaos theory. It cracked my head wide open. While reading this book, I moved from Seattle to San Francisco to join SLAP Skateboard Magazine as their music editor, but soon left to go back to school. I’d suddenly found that I wanted to do so much more than write about music.

frontwheeldrive.com started to reflect this shift in earnest in early 1999, and it’s been evolving ever since. We (myself and a few friends that help me out, mainly Tom Georgoulias and Brandon Pierce, but many of our interview subjects have gone on to become contributors) write reviews of just about anything that we find interesting and do interviews with people that we think are doing interesting things. Admittedly, it started with a focus on the fringes of science, but we’ve since (over the past six years) opened it up to include BMX, skateboarding, music, art, literature, and film along with the science. Like I said, just about anything we find interesting.

So, the impetus behind frontwheeldrive.com remains to collect and spread the word about cultural artifacts and the people that make them. I try not to limit the subject matter anymore because I view the mind as an ecology. For any ecology to grow and flourish, it needs diversity. New stuff comes not from the well-defined fields, but from the interaction between them. Allowing theorists, artists, BMXers, musicians, skateboarders, etc. to rub shoulders, frontwheeldrive.com attempts to cross-pollinate areas of interest so that new ideas can grow.

The zine HEADTUBE was my attempt to fill what I see as a void in BMX media. Back when I started doing zines, Freestylin’ Magazine really felt like it covered the culture of BMX — not just the riders, the products, the contests, and a few music reviews, but the culture surrounding the people who ride twenty-inch bikes. Andy Jenkins, Mark Lewman, and Spike Jones truly created something that doesn’t exist anymore. HEADTUBE was an attempt to bring some semblance of that back. I’m only speaking of it in the past tense because I haven’t gotten around to doing a second issue. I want to do it regularly, but graduate school and teaching have been keeping my other projects limited somewhat.

The zine HEADTUBE was my attempt to fill what I see as a void in BMX media. Back when I started doing zines, Freestylin’ Magazine really felt like it covered the culture of BMX — not just the riders, the products, the contests, and a few music reviews, but the culture surrounding the people who ride twenty-inch bikes. Andy Jenkins, Mark Lewman, and Spike Jones truly created something that doesn’t exist anymore. HEADTUBE was an attempt to bring some semblance of that back. I’m only speaking of it in the past tense because I haven’t gotten around to doing a second issue. I want to do it regularly, but graduate school and teaching have been keeping my other projects limited somewhat.

As much as possible, I try not to limit myself though. A few years ago, Ron Wilkerson told me, “If you don’t have it, you didn’t want it bad enough.” I took that to heart, and I try to pursue any and everything I want to accomplish — and I encourage everyone else to do the same. There’s no reason you can’t have everything you want.

BT: You write for more than a few websites aside from your own projects, and you’re also in the process of writing your first book. Can you tell us more about how you began contributing written pieces to websites, what sites you currently contribute to, and more about the book?

RC: The contributions to other websites are a result of a combination of the things I’ve done with frontwheeldrive.com, and my music journalism days. I still write about music on a regular basis for SLAP, and I wrote some pieces for Disinformation when that was something one could do (They’ve since switched up their format), and I think most of the other websites to which I contributed have changed hands or disappeared. I’m open though.

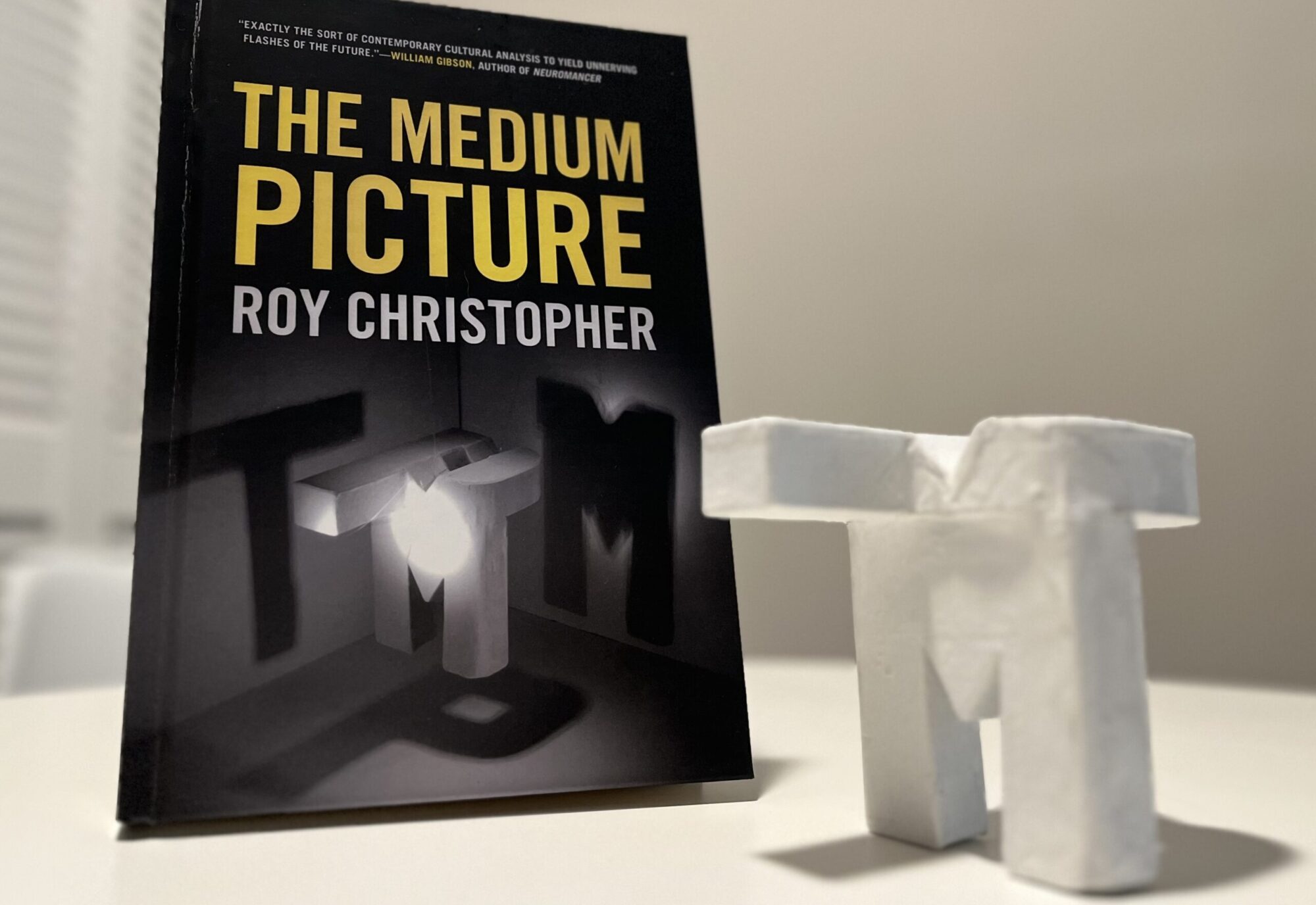

The book is called Actual Size: Culture on the Edge of the Underground, the Media, and the Mind. For the sake of brevity, I’ll just say that, in the broadest sense, it’s a quasi-theoretical exploration of how culture is created. I’m studying a lot of my favorite underground cultural phenomena with several of my favorite theories. It’s currently making its way around the book-publishing machine somewhere, so think happy thoughts.

I’ve also been helping Paul D. Miller (DJ Spooky) edit an essay collection called Sound Unbound: Music, Multimedia, and Contemporary Sound Art — An Anthology of Writings on Contemporary Culture, which will be out this fall on The MIT Press; throwing around project ideas with my friend Doug Stanhope; and finishing up my master’s thesis, among other things.

BT: Is BMX more of an escape now from everything else you do?

RC: I tend to recoil from the idea of escapism. I immediately think of the character in the novel Skinny Legs and All by Tom Robbins: In a discussion about “I’d Rather Be” bumper stickers, he said that if there “was something he’d rather be doing, he’d damn well be doing it!”

So, I don’t think of riding as an escape. BMX has given me so much over the years that I like to just act like I’m still a part of it. I was never sponsored beyond the bike shop level (though I do get unofficial flow from Ronnie Bonner at UGP, Dave Young at BLK/HRT, and Wiggins at Black Box), I only placed in an AFA contest once (2nd place, 14-15 Novice Flatland, 1985), the only time I’ve been in a BMX magazine (before now) was to get dissed by McGoo (Ride BMX, October/November, 1995), a Slayer feature I wrote (Ride BMX, June, 96), a few things I wrote for Faction BMX (one piece on Seattle ripper Steve Machuga and one, coincidentally, on zine-making — with a contribution from Lew), and a few music articles for the short-lived Tread, but I still get the same feeling from riding my bike as I did twenty-five years ago (I raced oh-so-briefly in 1979). As long as it feels that way, and my body holds out, I’ll be riding little kids’ bikes — as an escape or otherwise.

So, I don’t think of riding as an escape. BMX has given me so much over the years that I like to just act like I’m still a part of it. I was never sponsored beyond the bike shop level (though I do get unofficial flow from Ronnie Bonner at UGP, Dave Young at BLK/HRT, and Wiggins at Black Box), I only placed in an AFA contest once (2nd place, 14-15 Novice Flatland, 1985), the only time I’ve been in a BMX magazine (before now) was to get dissed by McGoo (Ride BMX, October/November, 1995), a Slayer feature I wrote (Ride BMX, June, 96), a few things I wrote for Faction BMX (one piece on Seattle ripper Steve Machuga and one, coincidentally, on zine-making — with a contribution from Lew), and a few music articles for the short-lived Tread, but I still get the same feeling from riding my bike as I did twenty-five years ago (I raced oh-so-briefly in 1979). As long as it feels that way, and my body holds out, I’ll be riding little kids’ bikes — as an escape or otherwise.

BT: You describe media as the intersection between culture and technology. How does this theory relate to the idea of making a BMX website, zine or video?

RC: Well, in the broadest sense, one of my main research interests is the influence of technology on culture. The study of media — and even that in my mind is quite broad — somewhat narrows the research to where the results of this collision play out. I’m focused on the domains of various youth cultures, so BMX media is where bikes, digital cameras, video cameras, writing, riding, music, and the like converge and capture the culture in time. When you watch a video or see a magazine from a certain era (think late-80s Plywood Hoods’ Dorkin’ videos, mid-90s Props, or an issue of Go or Freestylin’), you’re seeing a snapshot of BMX culture at that time. With that in mind, no one else is going to capture what you think is interesting, intriguing, or important, so that’s why I advocate making independent media — about BMX or whatever else you’re into.

BT: Finally, if you had to recommend some websites, both BMX and non-BMX, can you make some suggestions and why you’ve chosen them?

RC: Non-BMX-wise, I usually visit the sites of my friends to see what they’re doing. Folks like Steven Shaviro, Doug Rushkoff, DJ Spooky, Erik Davis, dälek, Milemarker, Doug Stanhope, and Howard Bloom. For BMX stuff, I usually go to Nev’s Backlash BMX site for news, and Jared’s site, Brian’s site, or company sites (like Terrible One or Underground Products) for the inside scoop. I keep a rotating list of links on my site. I tend to frequent sites that combine personality and insight with interesting subject matter.

[DIG BMX Magazine #46, May 2005]

[photo by Claire Putney.]

Mike Ladd: Rebel Without a Pause

Several years ago, my friend Greg Sundin gave me Mike Ladd’s Welcome to the Afterfuture (Ozone, 2000). I was instantly hooked. Ladd’s spaced-out beats and intelligent wordplay push the limits of hip-hop until they break into noisy splinters. Genre distinctions can’t hold the man. He’s been performing in every possible way since age thirteen, but his body of work reflects the very best that hip-hop can be. After digesting Afterfuture, I simply had to hear more.

Several years ago, my friend Greg Sundin gave me Mike Ladd’s Welcome to the Afterfuture (Ozone, 2000). I was instantly hooked. Ladd’s spaced-out beats and intelligent wordplay push the limits of hip-hop until they break into noisy splinters. Genre distinctions can’t hold the man. He’s been performing in every possible way since age thirteen, but his body of work reflects the very best that hip-hop can be. After digesting Afterfuture, I simply had to hear more.

Knowing that this would be the case, Greg explained that Ladd’s first record (Easy Listening 4 Armageddon [Mercury, 1997]), during which a lot of the stuff for Afterfuture was recorded) was difficult to find due to record label bullshit. Finding it became a personal mission that was finally accomplished a few years, a few states, and many record stores later (and it was well worth it). Ladd hasn’t made things much easier on me since. His records have come out on several different labels and often under one-off group names (e.g., the conceptual pair The Infesticons’ Gun Hill Road [Big Dada, 2000] and The Majesticons’ Beauty Party (Big Dada, 2003) — I wish I had the space here to tell you this story), but they’re always worth the search.

His latest outings include a collaboration with pianist Vijay Iyer called In What Language? (Pi Recordings, 2003), Nostalgialator (!K7, 2004), and Negrophilia (Thirsty Ear, 2005). Where In What Language? and Negrophilia are collaborative avant-jazz explorations (the latter includes the Blue Series Continuum, as well as Vijay Iyer), Nostalgialator is more like Ladd’s older stuff: straight ahead hip-hop, but twisted with his cerebral, poetic bent.

That said, all of Ladd’s music runs along a spectrum from head-nodding to mind-expanding, and it often sits dead in the middle, bringing your dome the best of both. Whether it’s grimy boom-bap, heady jazz, or whatever else he decides to explore next, Mike Ladd always brings it rugged and rough.

Roy Christopher: Tell me about Negrophilia. What were your aims with this record and how did it all come together?

Mike Ladd: The concept has been with me for a long time. I think in a way, all of my records have touched on this topic, especially when you are a Black artist doing stuff that doesn’t make the mainstream or is esoteric, and you have to contend with a large portion of your audience being white (especially when that wasn’t your primary intended audience). That said, when Petrine Archer-Straw’s book came around, I had to read it, and it touched on at least some of the origins of the Negrophilia phenomenon, a phenomenon that has grown beyond Elvis and is as bizarre as Michael Jackson, Eminem, and Condoleezza Rice having tea and smoking stems in a drum circle in Norway.

Mike Ladd: The concept has been with me for a long time. I think in a way, all of my records have touched on this topic, especially when you are a Black artist doing stuff that doesn’t make the mainstream or is esoteric, and you have to contend with a large portion of your audience being white (especially when that wasn’t your primary intended audience). That said, when Petrine Archer-Straw’s book came around, I had to read it, and it touched on at least some of the origins of the Negrophilia phenomenon, a phenomenon that has grown beyond Elvis and is as bizarre as Michael Jackson, Eminem, and Condoleezza Rice having tea and smoking stems in a drum circle in Norway.

RC: Why is that? Why is it that when Black artists create challenging Black music, their audience ends up being mostly white folks?

ML: The answer is actually pretty easy and is more of a class issue than a race issue. “Experimental music,” alternative music, underground, whatever you want to call it — music that doesn’t sell, sometimes on purpose — is hard to access. It’s hard to find at retailers and in the media — even the internet. It takes time to find it, and it usually takes a certain amount of effort to fully enjoy it. Generally speaking the people who can afford the time to pursue music this adamantly are often middle class or richer (poor, working-class white kids don’t come out in droves to see our shit either, and there is often a proportionate amount of middle-class kids of color at the shows).

For most people sitting and listening to music — especially music that takes time — is a luxury they either can’t afford or choose not to. If you bust your ass all day like most of the world does (even if you’re a yuppie who used to dig the occasional weird shit, but now has a job and a kid and has lost touch with his art friends), the last thing you want to do is come home and listen to some music that’s gonna make your head work more. What you’re making doesn’t have to be that esoteric either: With so much shit out there being pushed, it’s work for the average person to digest great music in an unclear package. On top of that, pop is further propagated by a culture that respects capital return over content in general. The culture that appreciates art that pushes boundaries is relegated to mostly bourgeois institutions, universities, etc.

For most people sitting and listening to music — especially music that takes time — is a luxury they either can’t afford or choose not to. If you bust your ass all day like most of the world does (even if you’re a yuppie who used to dig the occasional weird shit, but now has a job and a kid and has lost touch with his art friends), the last thing you want to do is come home and listen to some music that’s gonna make your head work more. What you’re making doesn’t have to be that esoteric either: With so much shit out there being pushed, it’s work for the average person to digest great music in an unclear package. On top of that, pop is further propagated by a culture that respects capital return over content in general. The culture that appreciates art that pushes boundaries is relegated to mostly bourgeois institutions, universities, etc.

That said, however, I would like to point out the gratifying experience of meeting someone at every show I have ever played that does not fit the demographic I just described, that is from the audience I love to access; it’s just that they are in small pockets spread out all over the world. It’s like a secret army.

But I don’t think you can make music these days without a deep respect for pop and the people who listen to it (I don’t care if you see it as understanding your adversary or knowing your global terrain). I actively ignored pop all through high school and college. I discovered absolutely amazing music in the process, but I missed out on some basic sensibilities that took me time to understand.

RC: Negrophilia followed pretty closely on the heels of Nostalgialator, yet these records are very different. How did you approach these different projects?

ML: I approached them in totally different mindsets, but I can’t really explain the shit. Nostalgialator was mostly written on the road touring, and recorded in Brooklyn. I did a bunch of Negrophilia at the same time with Guillermo Brown, who is instrumental in this record — this record is as much his as it is mine. At the bidding of the record label (for reasons I still don’t know), I finished Negrophilia alone in my apartment in Paris, which was a completely different environment than I had been used to. I think the difference can really be attributed to the great players on the record: Roy Cambel, Andrew Lamb, Bruce Grant, Vijay Iyer, and my niece, Marguerite Ladd. With Guillermo as coproducer, the collaboration helped it sound so different.

The short answer is that Nostalgialator is a “Pop” record, and Negrophilia is a “Music” record.

RC: You’ve jumped around with different sounds and styles throughout your work. Do you ever wonder or worry that you make it difficult for your fans to keep up with you?

ML: Yes, I’m broke because of it. I think I probably lose fans with every record, but hopefully gain new ones too. As long as some people stick with me, I’m going to keep exploring as many facets of myself and my interests as possible.

In 2005, I think it’s pretty naive for any American to think of themselves as culturally one-dimensional. Clearly our president does, and look at how he acts. Then again, look at the skin tones of his family and it’s all shifting quickly. The racial paradoxes in Bush are predictable and Machiavellian, but they still fascinate me, and I’m interested in how they will affect the world.

Okay, that’s off the point of the question, but maybe another answer to the problem you are presenting. The thing is, if I am the package and everything you hear from me is a coherent part of that package, I am simply regurgitating the influence and experiences that have informed me for a very long time. Eight records in, I am deeply grateful to the fans that have stuck with me, for real.

RC: Is there anything you’re working on that you’d like to mention here?

ML: Doing a new band called Father Divine for ROIR Records. Very happy with the way it’s coming along. Shout out to Reg in Colorado and DJ Jun.

Taj Mihelich: Terrible One

In the early 90s, the sport of BMX all but died. The magazines, sanctioning bodies, and many of the companies disappeared. In the void left, the pros of the previous era started their own companies and events, following the model Steve Rocco had established in skateboarding in the late 80s. With many of the old pros busy with companies and organizations and the field of riders thinned-out in general, this new milieu left room for new pros. It was during this time that Taj Mihelich emerged as one of BMX’s new stars. Continue reading “Taj Mihelich: Terrible One”

In the early 90s, the sport of BMX all but died. The magazines, sanctioning bodies, and many of the companies disappeared. In the void left, the pros of the previous era started their own companies and events, following the model Steve Rocco had established in skateboarding in the late 80s. With many of the old pros busy with companies and organizations and the field of riders thinned-out in general, this new milieu left room for new pros. It was during this time that Taj Mihelich emerged as one of BMX’s new stars. Continue reading “Taj Mihelich: Terrible One”

Mark C. Taylor: The Philosophy of Culture

Mark C. Taylor is one of those people you stumble upon and wonder why you were previously roaming around unaware. His countless books explore many areas of culture, philosophy, art, theory, and, most recently, commerce. I originally came across his work while doing research on artist Mark Tansey (Taylor’s The Picture in Question explores the mix of messages and theory in Tansey’s paintings). Continue reading “Mark C. Taylor: The Philosophy of Culture”

Mark C. Taylor is one of those people you stumble upon and wonder why you were previously roaming around unaware. His countless books explore many areas of culture, philosophy, art, theory, and, most recently, commerce. I originally came across his work while doing research on artist Mark Tansey (Taylor’s The Picture in Question explores the mix of messages and theory in Tansey’s paintings). Continue reading “Mark C. Taylor: The Philosophy of Culture”

Aesop Rock: Lyrics to Go

If, as Marshall McLuhan insisted, puns and wordplay represent “intersections of meaning,” then Aesop Rock has a gridlock on the lyrical superhighway cloverleaf overpass steez. Every time I spin one of his records, I hear something new, some new twist of phrase, some new combination of syllables. These constant revelations are precisely why I’ve been a hip-hop head since up jumped the boogie, and Aesop keeps the heads ringin’. I’d quote some here, but you really just have to hear him bend them yourself. Continue reading “Aesop Rock: Lyrics to Go”

If, as Marshall McLuhan insisted, puns and wordplay represent “intersections of meaning,” then Aesop Rock has a gridlock on the lyrical superhighway cloverleaf overpass steez. Every time I spin one of his records, I hear something new, some new twist of phrase, some new combination of syllables. These constant revelations are precisely why I’ve been a hip-hop head since up jumped the boogie, and Aesop keeps the heads ringin’. I’d quote some here, but you really just have to hear him bend them yourself. Continue reading “Aesop Rock: Lyrics to Go”

Hal Brindley: Wild Boy

Remember when thoughts and theories about so-called “Generation X” were on the tip of everyone’s tongue? We were called “slackers,” and older people said we lacked motivation and passion. I’ve always taken issue with these characterizations because I’ve constantly seen people my age pursuing paths and interests that had no prior archetype — and working very hard at them. Now that the focus has shifted to the next generation, and now that we’ve been pushing for a while, our generation is emerging in new careers and pursuits quite different from our forebears — and in many that didn’t exist before. Continue reading “Hal Brindley: Wild Boy”

Remember when thoughts and theories about so-called “Generation X” were on the tip of everyone’s tongue? We were called “slackers,” and older people said we lacked motivation and passion. I’ve always taken issue with these characterizations because I’ve constantly seen people my age pursuing paths and interests that had no prior archetype — and working very hard at them. Now that the focus has shifted to the next generation, and now that we’ve been pushing for a while, our generation is emerging in new careers and pursuits quite different from our forebears — and in many that didn’t exist before. Continue reading “Hal Brindley: Wild Boy”