Earlier this year, Mark Lewman somehow conned Nike into funding the FREESTYLIN’ Magazine reunion book he’s been wanting to do since FREESTYLIN’ stopped printing pages in the early 90s. Having finally received my copy, I am glad he did. Continue reading “The FREESTYLIN’ Book”

Space-Based Solar Power FTW

My friend and mentor Howard Bloom created this video with Buzz Aldrin, Edgar Mitchell, and a crew of renegade NASA insiders to raise awareness about space-based solar power as a possible remedy for the global energy crisis. They introduce the piece with the line “A Message for the Next President of the United States.” Continue reading “Space-Based Solar Power FTW”

33 1/3: Books About Records

Writing about music is like dancing about architecture.

The line above has been attributed to several voices — Elvis Costello, Miles Davis, Frank Zappa, and Lester Bangs, among others — but if the roof is on fire, I say we dance. Continuum’s 33 1/3 Series, helmed by the insightful and inimitable David Barker, is good books all about good records. Not just “good” records, but records that changed the face of music in one way or another — records that set the roof aflame, and the two I just read — Paul’s Boutique by Dan LeRoy and Loveless by Mike McGonigal — are just that.

I know, what can possibly be said about Paul’s Boutique and Loveless that you haven’t already heard some drunken music geek say jumping up and down waving his or her (probably his) hands? I thought the same thing, but having been that drunken, hand-waving music geek more than once in the past, I was still interested.

Coming out of the wake of the Hip-hop parody that was License to Ill (Def Jam, 1986), The Beastie Boys surprised everyone with the sample-heavy psychedelia of Paul’s Boutique (Capitol, 1989). Upon its initial release, the record’s public response could be described as “doom” for The Beastie Boys’ career, but over the years it has proven itself one of the most important records of its time, and possibly the most creative sample-based record ever made.

The Beastie Boys were seemingly riding high after their many tours supporting License to Ill. On the contrary, they were ready for a break and ready to get paid, but their bosses at Def Jam were not about to offer them either of these. The suits neuvo there were stuck in a cashless lurch with their newly minted distribution deal with Columbia and anxious for a new record from the Beasties. This would not do. So, our heroes bounced to the Left Coast, found some new friends, some new collaborators, a lawyer, and a new label. Finally paid by a sweet advance from Capitol, the boys were set to blow off some steam and start work on what would become their undisputed masterpiece.

The Beastie Boys were seemingly riding high after their many tours supporting License to Ill. On the contrary, they were ready for a break and ready to get paid, but their bosses at Def Jam were not about to offer them either of these. The suits neuvo there were stuck in a cashless lurch with their newly minted distribution deal with Columbia and anxious for a new record from the Beasties. This would not do. So, our heroes bounced to the Left Coast, found some new friends, some new collaborators, a lawyer, and a new label. Finally paid by a sweet advance from Capitol, the boys were set to blow off some steam and start work on what would become their undisputed masterpiece.

While the Beastie Boys were sorting out their post-License to Ill lives, a loose-knit group of DJs and producers was busy creating the soundtrack to their next era. Among these were John King and Simpson (The Dust Brothers), Matt Dike (DJ, promoter, Delicious Vinyl founder), and Mario Caldato Jr. (studio engineer). Paul’s Boutique would eventually include the music of many — real (?) and sampled.

Dan LeRoy’s book gets at how this all came together, and — it’s an interesting and illuminating read about a particularly mysterious time in the Beasties’ history. LeRoy’s insightful epilogue regarding nostalgia is also not to be missed.

Say what you will about The Beastie Boys, but Paul’s Boutique is the record that synced their placement in the alphabet and their placement among music legends: right between The Beach Boys (Pet Sounds) and The Beatles (Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band).

Not unlike Paul’s Boutique, My Bloody Valentine’s Loveless (Creation, 1990) is widely considered — and rightfully so — one of the most important and influential records of the 90s. Also like Paul’s Boutique, its making is shroud in rumor. Such myths (e.g., that it cost half a million dollars to record and bankrupt their label Creation only to be saved by Oasis, Kevin Shield’s notorious studio meticulousness, that there are thousands of guitar overdubs, etc.) are either clarified or dispelled herein.

Not unlike Paul’s Boutique, My Bloody Valentine’s Loveless (Creation, 1990) is widely considered — and rightfully so — one of the most important and influential records of the 90s. Also like Paul’s Boutique, its making is shroud in rumor. Such myths (e.g., that it cost half a million dollars to record and bankrupt their label Creation only to be saved by Oasis, Kevin Shield’s notorious studio meticulousness, that there are thousands of guitar overdubs, etc.) are either clarified or dispelled herein.

Mike McGonigal does some digging for the roots of the signature My Bloody Valentine sound that was refined on Loveless and defined an era and countless imitators (also mentioning such worthy influences as Sigur Rós, Mogwai, M83, and Caribou, but spending a disproportionate number of pages on Rafael Toral), but how he went the whole book without mentioning Robert Hampson, I do not know. He does warn that writing about this record can make you “start believing it’s the most transcendent record ever,” and that “it’s too easy for this album to turn you into a pretentious twat. Be very careful!!!” Thankfully, he avoids hyperbole except where appropriate and taps into why this beautiful wall of guitar noise remains the touchstone that it is.

These two books pull back the curtain on their respective subjects, giving us a glimpse behind the mystery surrounding both. So, if you’ve been that drunken, hand-waving music geek or know someone who has, these two books (as well as the rest of Continuum’s 33 1/3 Series, including books on Reign in Blood by Slayer, Daydream Nation by Sonic Youth, …Endtroducing by DJ Shadow, Unknown Pleasures by Joy Division, Led Zepplin IV, Bee Thousand by Guided by Voices, among many others) will help explain the phenomenon.

Now if I could just convince David Barker to let me do one… (Right?)

—

I cannot resist adding the video for My Bloody Valentine’s “To Here Knows When” (runtime: 4:43) from which the cover art for Loveless was gleaned. It’s absolutely perfect.

Sonic Youth: Goodbye 20th Century

No band has been more consistent while simultaneously being more experimental than Sonic Youth. Ever. When it comes to making great records while still pushing the limits of themselves and their listeners, Sonic Youth are the reigning ensemble. I doubt that anyone in the know — fan or foe — would contest that. In Goodbye 20th Century (Da Capo), their first authorized biography, David Browne wades through waves of feedback and gets behind the amps of the nearly three decades of noise from this veritable institution of American music. Continue reading “Sonic Youth: Goodbye 20th Century”

No band has been more consistent while simultaneously being more experimental than Sonic Youth. Ever. When it comes to making great records while still pushing the limits of themselves and their listeners, Sonic Youth are the reigning ensemble. I doubt that anyone in the know — fan or foe — would contest that. In Goodbye 20th Century (Da Capo), their first authorized biography, David Browne wades through waves of feedback and gets behind the amps of the nearly three decades of noise from this veritable institution of American music. Continue reading “Sonic Youth: Goodbye 20th Century”

David Byrne’s “Playing the Building” on BBTV

My favorite Talking Head, David Byrne, turns an entire old building in New York City into a giant sound machine in an installation called “Playing the Building.” Xeni Jardin takes a tour. Continue reading “David Byrne’s “Playing the Building” on BBTV”

Cadence Weapon: Check the Technique

I am hereby requesting a bandwagon late-pass. Out of nowhere a few months ago, someone sent me the video for “Sharks” by Cadence Weapon (embedded below). Like many who’ve heard the track, I was instantly hooked, and started looking for more. Well, lucky me, Cadence Weapon had just put out a new disc of his glitchy Hip-hop called Afterparty Babies (Anti, 2008). It’s been in or near the top of the playlist ever since.

I’ve been down since thirteen literally, bombing the whole system up, beautifying the scenery. — Big Juss, Company Flow

Before dropping the bubbly beats and fresh rhymes, Cadence Weapon a.k.a. Rollie Pemberton used to write reviews for a major music website, but way before that, his dad was Edmonton, Alberta’s premiere source for Hip-hop. At age thirteen, Rollie knew he wanted to rap, and his starting young is evident in the work: His records — though he’s only been making them for a few years — are those of a veteran. He’s grown up with this ish. It’s in his bloodstream.

Clever and catchy Hip-hop that doesn’t outsmart itself might be more prevalent now than ever, but it still isn’t lurking on every airwave. I’m glad to pass the name Cadence Weapon on to you. He gets respect for the rep when he speaks. Check the technique and see if you can follow it.

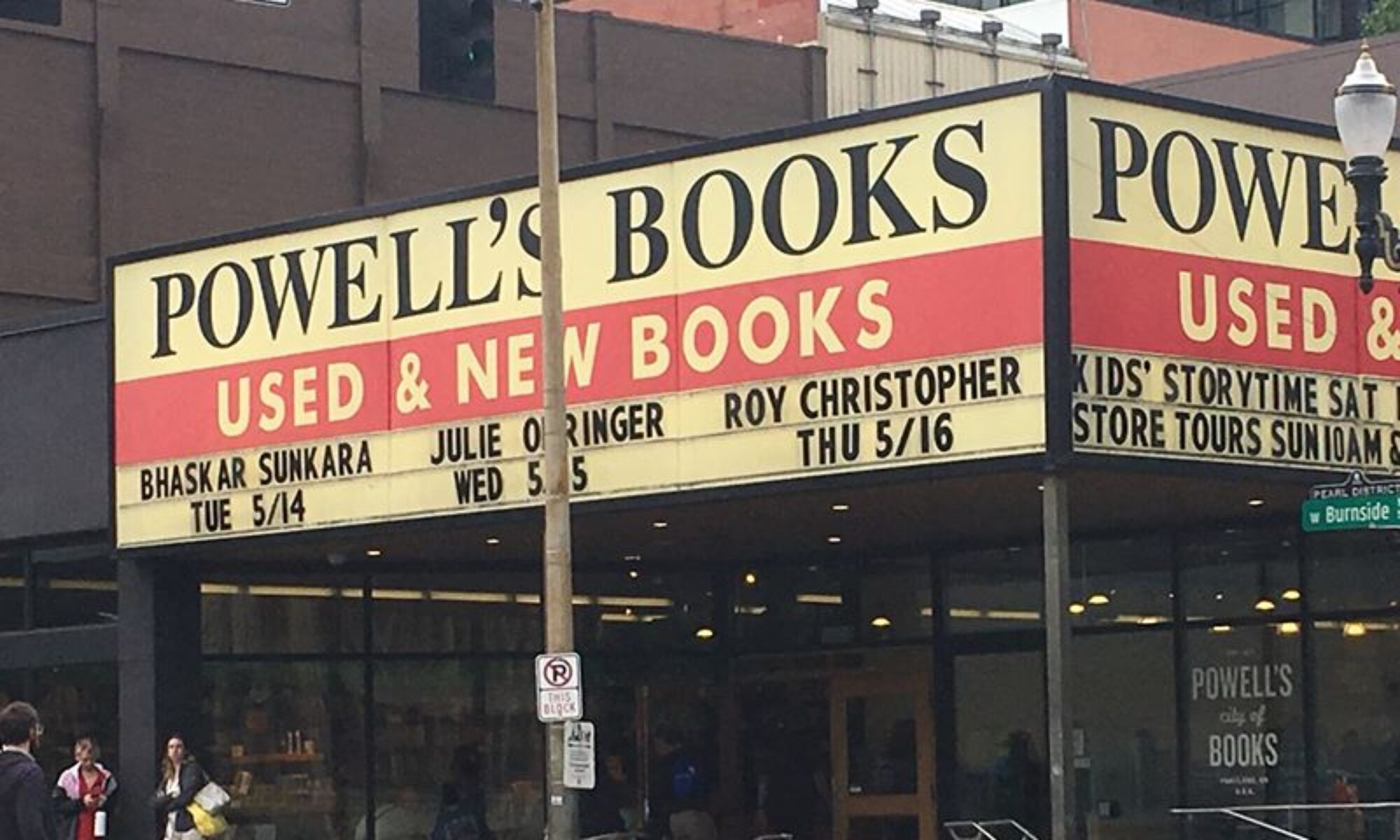

Roy Christopher: Tell me about the new record. What’s different this time around?

Cadence Weapon: This record is faster paced, more cohesive and tied to a connecting concept. It’s more personal and drawing from more dancefloor influences than IDM or grime.

Cadence Weapon: This record is faster paced, more cohesive and tied to a connecting concept. It’s more personal and drawing from more dancefloor influences than IDM or grime.

RC: Your dad was a Hip-hop pioneer up there in Edmonton. What are your earliest impressions of Hip-hop and music?

CW: I grew up on rap music and culture so I just saw it as normal. Predictably, I was isolated not knowing many other people who were into rap music so it was just something I liked myself. I saw it as an extension of poetry or any other artistic expression, and I still do.

RC: Though Hip-hop as a genre is often innovative and rebellious, it’s also steeped in strict traditions and rules. What’s your take on this contradiction — and negotiating it as an artist?

CW: It’s one of the strangest things about the music. It’s the most open-ended genre in terms of possibilities. You can sample someone walking down the street and rap about your mom’s hat if you wanted to, because there are no constraints in rap, just the ones built by the individual. The regimented nature of rap is a response to its corporate status: People thinking you have to maintain the status quo to retain sales. It’s shitty.

RC: Comedian David Spade once said that acts spend the first part of their career looking for a hook and the rest of it trying to bury that hook. To me, this is analogous to one having a “hit” (e.g., De La Soul’s “Me, Myself, and I,” or more recently, Aesop Rock‘s “No Regrets”) Do you ever resent the attention you got from “Sharks”?

CW: The success of “Sharks” doesn’t bother me. As with any single, it’s seen as representative of who I was at the time of its release. It’s a catchy song, it’s youthful and aggressive and not necessarily who I am right now, but I accept it as a period in my life. I am not trying to get rid of the memory of that song, I feel like there are still layers to it that people haven’t necessarily uncovered.

RC: What’s next for Rollie Pemberton? And for Cadence Weapon?

CW: Next for Rollie Pemberton: making the most of my free time, playing basketball, getting back into party mode, bettering myself.

Next for Cadence Weapon: actually collaborating with people on my next album, writing about death and body image and the other side of the world, starting a band, rapping harder.

———-

Here’s the video that launched the fandom, “Sharks” from Cadence Weapon’s debut record, Breaking Kayfabe (Upper Class, 2005) (runtime :4:22):

Rest in Peace: Three Giant Influences

Not normally one to dwell on such things, I thought it would be appropriate to acknowledge a few recent deaths, as the lives of these people impacted mine in profound ways. Continue reading “Rest in Peace: Three Giant Influences”

Dave Allen: Every Force Evolves a Form

I can’t remember the first time I heard Gang of Four, but I do distinctly remember a lot of things making sense once I did. Their jagged and angular bursts of guitar, funky rhythms, deadpan vocals, and overtly personal-as-political lyrics predated so many other bands I’d been listening to. Dave Allen was the man behind the bass, and now he’s the man behind Pampelmoose, a Portland-based music and media blog. Continue reading “Dave Allen: Every Force Evolves a Form”

I can’t remember the first time I heard Gang of Four, but I do distinctly remember a lot of things making sense once I did. Their jagged and angular bursts of guitar, funky rhythms, deadpan vocals, and overtly personal-as-political lyrics predated so many other bands I’d been listening to. Dave Allen was the man behind the bass, and now he’s the man behind Pampelmoose, a Portland-based music and media blog. Continue reading “Dave Allen: Every Force Evolves a Form”

I Check The Mail Only When Certain It Has Arrived

The mailbox at my parents’ house in Alabama is at the end of winding asphalt strip, the only interruption in acres of sporadic deciduous trees, save their house of course. One day almost exactly twenty years ago, some of the best mail I ever received happened upon that mailbox. Continue reading “I Check The Mail Only When Certain It Has Arrived”

The Just Noticeable Difference

Marié Digby was lauded as the internet’s next big find, a phenomena that had grown organically through digital word-of-mouth, but the media’s multi-roomed echo chamber told on itself. Maybe it was too much, too quickly, but just after Digby’s couple of homey, simple YouTube videos started spreading online, she was featured on radio stations, MTV, iTunes, announcing that she’d been signed to Disney’s Hollywood Records. The official press release headline read, “Breakthrough YouTube Phenomenon Marié Digby Signs With Hollywood Records.” What didn’t come out until later was that her name appeared on that dotted line a year and a half previous. Her online “discovery” was orchestrated from around long, conference-room tables.

Digby wasn’t unlimited bandwidth’s first phony phenom. YouTube’s avidly watched Lonelygirl15, a high school anygirl with a webcam, turned out to be nineteen-year-old aspiring actress Jessica Rose. She’d answered a Craigslist ad for an independent film, landed the part, and — after the “directors” did a bit of explaining — became Lonelygirl15. There was no product attached to the project, but all involved made names for themselves and are now well-represented in Hollywood.

These two stories are postmodern-day examples of what it takes to break through our media-mad all-at-once-ness and get noticed, to float some semblance of signal in a sea of noise. To experience the new is really just to notice a difference. In psychophysics it’s called the just noticeable difference (the “jnd”). Creating that difference is becoming more and more difficult as the tide of noise rises higher and higher.

Where Hollywood records and the Lonelygirl15 crew manipulated an emerging media channel, Miralus Healthcare took the opposite tack with their HeadOn headache remedy. They took one look at new media and ran the opposite direction. The original HeadOn television spot, which some ironically claim induces headaches, looks like a print ad and sounds like a broken record. But it worked. The commercial stood in such stark contrast to everything else on TV that the product is known worldwide.

It is sometimes claimed that technology makes it so that anyone can perform a certain task, like Photoshop made everyone an artist or Pro Tools made everyone a record producer. We make or tools and our tools make us (as Marshall McLuhan once said), but our tools do not make us great.

The idea that the internet and Pro Tools and — whatever else the advent and proliferation of the computer hath wrought — enables anyone to be an artist is both true and false. True, everyone has the tools to do so, but so few people have the talent. The latter is and always will be the case.

New technologies are normalizing events. Think of it like a crosstown street race where the traffic signals are normalizing events. One might be in the lead for a good bit of the ride, but as soon as everyone is stopped at a traffic light, the race effectively starts over. By way of convoluted analogy, one might be “ahead” in the home production process until Soundforge’s new software hits the scene.

Sure, there are people making money producing music who are not that good, but that doesn’t mean that anyone can compete with Dr. Dre just because he or she sets up a MySpace page and posts some loops from Acid. I’ve heard this argument so often lately, that anyone can cut-and-paste a record together and become a producer. If that were true, then why does Dr. Dre even have a career? Simple: Because he’s good at what he does. Let everyone try it!

Yes, building a name is a huge part of this and one person’s bloated name can overshadow someone else’s immense talents, but the proliferation of tools and channels does not dilute the fact that it takes talent, skills, work, and chance — as an artist and a marketer — to get noticed. Computers, the internet, weblogs, and everything else haven’t made everyone a great writer and killed authors’ careers.

DJ Scratch nailed it when he said, “The reason we respect something as an art is because it’s hard as fuck to do.” Good production, good writing, and good marketing are still hard to do — and it’s getting harder and harder to get them noticed. New tools and new channels don’t change the talent and effort it takes to capture the attention and the imagination of the masses, but a new twist here or there can make the just noticeable difference, and that can be all the difference in the world.