In November 1993, a few months after I first moved to Seattle, I went to see Washington, DC’s Tsunami at the late, legendary RKCNDY. It was a magical time in a magical place, and I was marveling as the names on record sleeves and magazine pages emerged in the flesh. At the merch table, I met Fontaine Toupes of Versus (who signed my Versus 7” “Seattle ain’t shit!”), my friend and collaborator to this day Tae Won Yu, as well as Kristen Thompson and Jenny Toomey of Tsunami and Simple Machine Records.

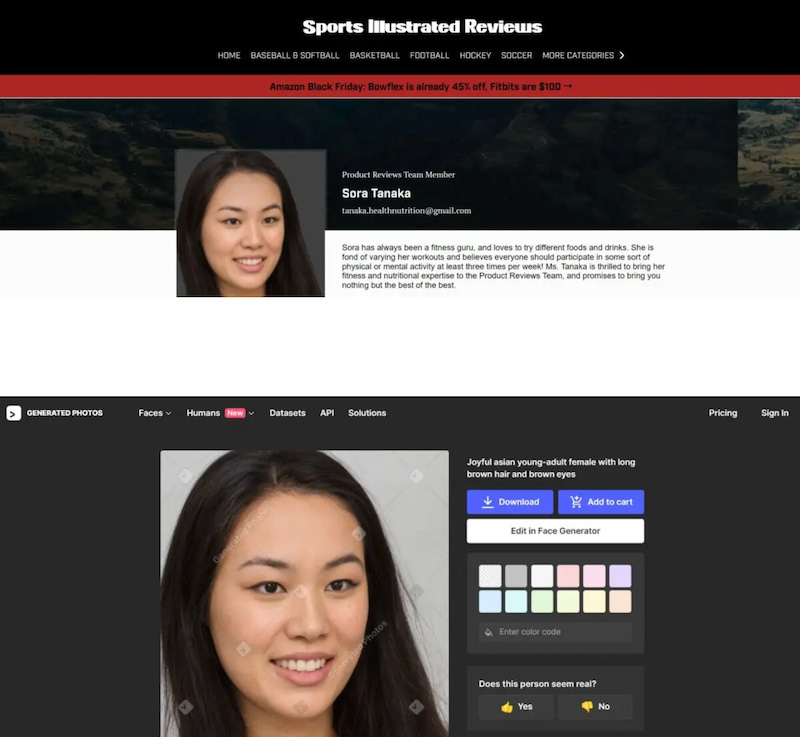

Toomey is a towering figure in 1990s punk rock, playing in bands, running a record label, and so much more. She and Kristen Thompson, put out The Introductory Mechanic’s Guide to Putting Out Records, Cassettes, and CDs [.pdf link], which was repeatedly updated with new and better resources over four editions throughout the 1990s. After releasing nearly 80 records, Simple Machines ceased operations in 1998.In the meantime, Toomey has continued quietly trying to figure out how technology can serve music and musicians. She was the founding executive director of the Future of Music Coalition, and she worked in various roles at the Ford Foundation. She’s also working on a book about all of this stuff. In her recent op-ed piece for Fast Company, she recognizes a pattern repeating. Likening generative AI to the file-sharing wave of the early 2000s, she writes,

The potential bait and switch of the tech world today is worryingly reminiscent of the early 2000s. While new technology always promises a flashy quantum leap into utopia, it instead regularly delivers opaque systems that streamline mistakes from the past. Throughout 2023’s frenzied AI debates, my feelings of déjà vu have become undeniable.

After years working behind the scenes, Jenny Toomey is thankfully emerging again.

Roy Christopher: When the impact of the internet started to dismantle the music industry as we knew it, many touted it as a new DIY revolution, returning the means of production to the people. What did you see?

Jenny Toomey: I didn’t see it flatly that way. In the same way that I didn’t feel like punk rock solved the problem of consolidated corporate media. I mean, if you look back at the hippie movements, you can criticize some of the hippies as being sort of just hedonist utopic people in denial about the systems in the world and just rejecting them (drop out), and then you can think of other ones as pragmatic utopian people who say that if we’re going to live a different way, we have to model how to live that different way which is more “drop in” or Whole Earth Catalog or Our Bodies Ourselves or eventually DIY punk.

That’s the element of counter culture and punk that I really liked. Not the flashy nihilism of tearing the old down, but rather the joyful enthusiasm of building the new. Asking that increasingly unasked question, “Why are we consenting to so many things we don’t agree with? And what would it look like if we tried to build different systems to give us more and better choices?” So, putting out your own records is a piece of it. A nice piece… nothing wrong at all with putting out your own records, but it’s not going to solve the problem of highly concentrated corporate media systems in late-stage capitalism. It does offer you a way to not completely condone what you abhor. Simple Machines was very much about that… grasping at, or rebuilding a small patch of agency.

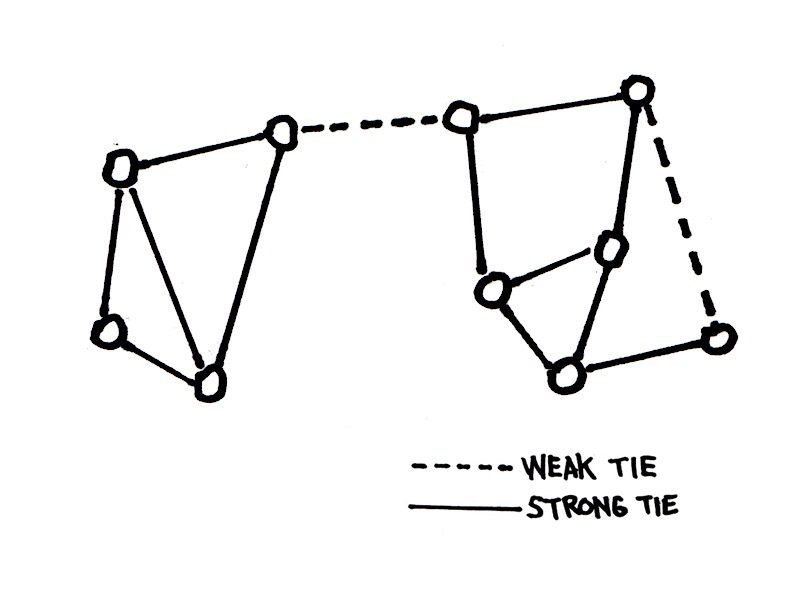

With Future of Music, it was a little bit more trying to bridge those two things, saying we’re actually at an inflection moment where the systems are going to change, and if we could model more open systems, more transparent systems, systems that artists had more say in the design of and more benefit from, then we might get both things. We might get to avoid the systems we hate while actually contributing to building new systems that we could love.

And for me, there was an idealism to it that came out of coming from DC and a kind of can-do quality, that kids that were my age that grew up in DC felt empowered—to DIY, to make your own thing. But we were also practical and pragmatic, because we’d done some of this before. When we put out The Guide to Putting Out Records, and we saw that it took on both of those problems at the same time. First, the guide let novices get on third base and be in charge of their own punk-rock destiny and put out their own records because we spelled out the recipe. But the advice and guidance in the guide wasn’t neutral, it embodied certain values. It looked across the scene and modeled better behavior and therefore it influenced how the scenes functioned. So, if a pressing plant was using bad vinyl, we wouldn’t recommend them, and if a distributor wasn’t paying independent labels, we would take them out of our recommended list of distributors, and if somebody like Barefoot Press was doing great work, we would enthusiastically promote them. It was a way of putting our thumb on the scale to amplify the kinds of behaviors and values and relationships and systems we wanted built.

RC: That was just the beginning though, right?

JT: Yeah, that’s what we were trying to do initially, before we started the Future of Music Coalition. We were just trying to figure out the best path forward for our own catalog. Kristin Thomson from SMR and Tsunami and I started the work as a project we called “The Machine,” which was basically a blog on Insound’s website that allowed us to share whatever we were learning about the music/tech space in real time. We would just sort of reflect on all of the different music distribution systems that were reaching out to Simple Machines as potential partners because there were like dozens of different companies that were all starting up. They all had different business models. Some would buy your copyright outright, and some would license it, and some would encrypt your music, some would stream, some would download. We had no clear idea which of these options were better or worse. So, a lot of what we were doing was trying to understand the trade-offs and make our best recommendations based on guidance from different experts that we ran into in our travels. Very often, once we’d published something, other experts would come forward and disagree with some aspects of what we’d written and that back-and-forth would allow us to refine our recommendations and make the information even better.

We thought, let’s just do this until we can figure out what we want to do with our own catalog. Because we had like 80 releases and we had no idea what to do with them. Ultimately the music tech bubble began to burst, companies began merging and going out of business and getting sued by the major labels and we realized that that the emerging system wasn’t solid enough for us to recommend any of these companies. That’s when we knew we needed to set up an advocacy group. We couldn’t just recommend a good and trustworthy company, because that company would be out of business in a few months. Everything was in flux. Instead we realized we needed to advocate for a set of systems.

RC: That systems mindset is so important, zooming out enough to see the context of the changes you can and can’t influence.

JT: We believed that instead of just waiting around until everything was set in stone according to the desires of the most powerful companies, we could identify more artist-friendly systems we wanted to advocate for. That’s what it was about. And FMC served quite a useful purpose for a number of years, but then the bubble burst and the collapse of the marketplace put a lot of the idealists on their back foot and the concentration of control began to reestablish itself until it turned into the system we live with now.

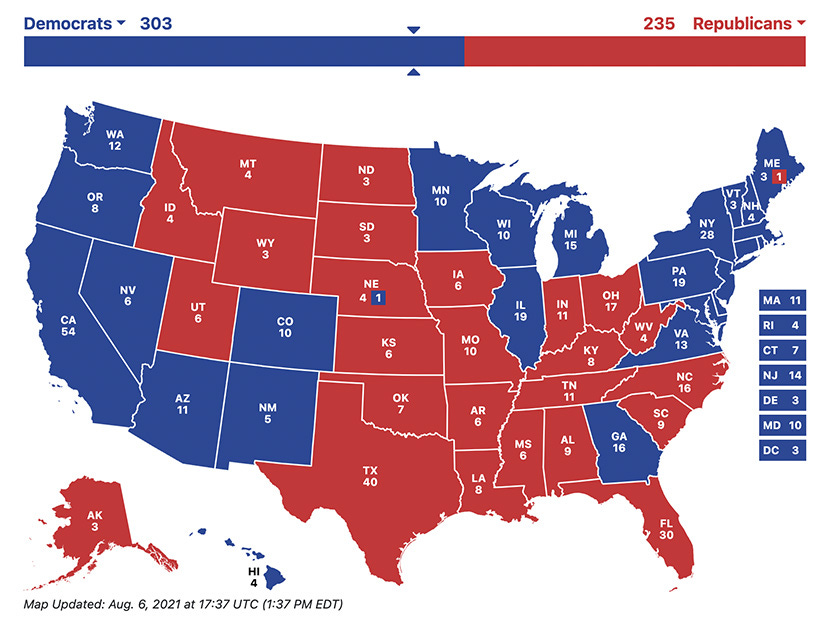

It’s hard to remember the level of constant polarized propaganda that we live within now was once uncommon. Today controversial issues are sorted into a quick binary, and everybody finds themselves on one team or another in relation to most things. But that didn’t really exist back then. The internet started as a way to let a billion flowers bloom but ultimately played a starring role in fomenting that polarization. Just around the time that I left Future of Music. It felt like the copyright issues had become a total religious war. There was no discussion about the merits of the different opinions, and you were either on the team that were Luddites or you were artist-hating thieves. It was all caricatures, and in many cases the only ones who benefited from the public battles were the companies.

One of the main reasons I went to the Ford Foundation was to work on these questions at a systems level… I felt like we were not going to be able to build better systems if we were just focused on music. Music was the canary… It was the first industry where we could see the tech and society clashes, the trade-offs, the stakes. The systems that we were developing out of the music battles were on a path to impact all the other systems of journalism and publishing and film and democracy and everything else… as we’ve seen.

The systems that we were developing out of the music battles were on a path to impact all the other systems of journalism and publishing and film and democracy and everything else.

We forget that in the time before the internet there were public interest battles that led to rules that regulate newspapers, radio stations, TV…constraining the behavior of those who control the information pipelines. People fought to establish community-input requirements, ownership limits, and regulations to balance thought, constrain bias and propaganda. All sorts of rules and regulations existed for traditional media. But very few of those protections were extended clearly into the internet environment. Or if the rules did theoretically extend into this internet environment, it wasn’t clear how they would be enforced and by whom. So both the legacy media and the emerging tech companies went on the offensive and were able to use this moment of public disagreement and confusion as a fig leaf or fog behind which they successfully advocated for reduced regulation altogether. And that’s the world we’ve been growing accustomed to over the past 20 years. But it didn’t have to be this way.

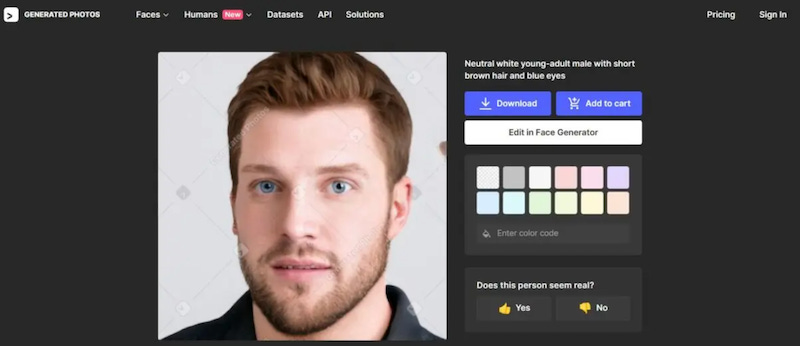

Actually, the reason I started writing about music recently is because I feel like that same land-grab is happening all over again in the AI space. The optimism that I felt in the 90’s about the potential for the internet to transform society into a better place has disappeared and been subsumed into a kind of overwhelming powerlessness and pragmatic nihilism. An acceptance of how little protection we can expect from these surveillance and consumption systems that have basically threaded themselves through all of society. So, the piece I wrote for Fast Company was just trying to remind people of a time back when it was a smaller set of problems, focused on music. In retrospect it’s clear to me that we didn’t have to make the choices we made, and we shouldn’t have trusted the companies on either side to protect us because it’s now absolutely clear that they exploited us. And maybe we can learn something from that.

RC: Here’s hoping!

JT: I think part of this problem is now everybody is so dependent on the tech systems that validate them with likes and attention we’ve all come to think of ourselves as a brand, and everything’s intermediated in that way. There is so much time spent on navigation and optimization… that somehow if we do everything right, two-factor authentication and just the right amount of self-promotion and other bootstrappy bullshit, we can win the rigged casino game. It’s very strange to me, but we also just assume these bad systems are the best we can possibly have and that they are permanent. They don’t have to be, but we’ve lost the outrage and the imagination that we’d need to remake them.

RC: That’s one of the things you’ve been able to see very clearly, is that none of this is permanent. It’s going to change again.

JT: Right, right.

RC: There seems to be something fundamental about abandoning analog practices for their digital equivalents—or simulations thereof—that puts human authenticity in peril. Do you think that there’s a distinction there that’s meaningful?

JT: Yeah. The vertical integration of everything and the co-mingling and codependence of information, creativity, community, labor and the systems of delivery, commerce and connection all through a self-dealing commercial gateway mostly designed by technologists who never took a humanities class… It’s disgusting and it’s obviously tremendously dangerous.

You and I are a bit older and technology was perceived in a completely different way when we were growing up. So, to give you a personal example, I very, very reluctantly took a typewriting class in junior high because I believed I was going to be a powerful woman who was never going to work as somebody else’s secretary. The association to typing back then was clerical. There was a status association to whether you did the “thinking work” or whether you did “technical work” supporting the thinkers. And in the 80’s women were still very often seen as the supporters and not the thinkers. So, as a feminist, I felt reluctant to even learn typing because typing was associated with a service role I didn’t see for myself.

When the internet came, that shifted dramatically. If you couldn’t type or understand the value of typing as the gateway into the internet you were gonna seem outdated and square. I remember my mother left a pretty powerful job running a large non-profit. When she was trying to get her next job she had grown fond of saying, “I don’t even know how to type.” It was a badge of honor… a marker of her status as the type of woman who isn’t a secretary but who has a secretary. And I remember saying to her, “If you want to get your next job please don’t ever say that out loud again.” In the space of maybe five years “up” became “down”… and that’s just one example of how dramatic the shift was and how opaque and slow the cultural catch-up was for so many people, particularly my generation and those who were older.

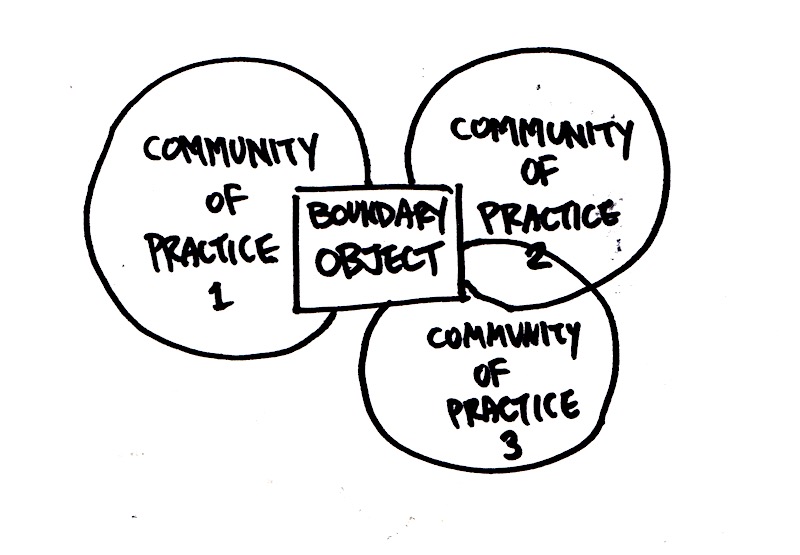

RC: There are all of these invisible boundaries we find each other behind.

JT: When I went to Ford initially, that “othering” of tech was commonplace. Almost every single person who was recruited to run programs came from the academy, organizing, legal advocacy, policy advocacy—respected careers on the humanities side. Many of them carried with them bias-against, or incredulity or aversion-toward, tech as compared to the disciplines they studied and revered. This meant that they were incurious and had a gap in understanding just how thoroughly tech was transforming the landscape where they did their work. So, the smartest people, the ones with the power to stop it, sat back without contesting much of what the tech companies were doing till it was too late.

And it wasn’t until much, much later when I had a different role at Ford that we did research that allowed us to see that even the universities who were best prepared to graduate hybrid tech-experts, were actively siloing the tech away from the humanities. And we can all see how that turned out. So many of the clunky technical systems we are forced to use everyday (and live within) were designed by guys who were solving a technical problem on a deadline in a humanities-less void.

So, I think my major point is this one: We didn’t have to go into an environment where the internet was completely unregulated, because when you scratch the surface of the historic media rules—the rules that we have for telephones and the rules that we have for privacy and the rules that we have for equal opportunity and thousands of others—all of these rules should be enforced within the internet environment. But the advocates and the leaders who ran the nonprofits or the regulatory agencies that advocated for establishing and enforcing those historic rules were scared of tech, or functionally blind to tech. This meant that they functionally ceding enforcement. They back-burnered governance for long enough to normalize a digital world that lacks public protection. And while that was happening the tech companies became more powerful than the robber barons, and we all became complicit and dependent upon the systems they control.

RC: Is there a way out of that?

JT: There have been some moments of protest over the past 20 years, where artists have tried to demonstrate the value of their labor and their agency by saying, “I’m not going to be in your Spotify, or I’m going to build my own internet player that’s going to be artist controlled” or whatever. But in the meantime as the market becomes more streamlined and consolidated the stakes have become existential. The centralization of recommendation through the music players actually determines who can be seen as a legitimate artist and who is invisible. What’s worse, as the markets become integrated, how you are seen or “not seen” in those environments determines other things… whether you get enough attention to be paid any royalties whatsoever from Spotify… whether a venue will book your band without a certain number of likes or followers etc. We couldn’t even get a professional Spotify account for Tsunami if we didn’t have a Tsunami Instagram page to link it to. It’s way worse than I expected where all but the most powerful artists are forced to shop at the company store just to be in the game. And each post those artists reluctantly put out there to try to develop an audience is just more labor and content extracted to sell ads and train large language models, generating profits they will never share. So you go to Bandcamp to keep it real in the indie-sphere and that platform is actually owned by a Video game company and then they sell it… and you have to wait for the other shoe to drop… So, that just another reason to work with the largest companies that might not go away. Yuck.

I also wonder if that desire to be outsider and not self-promoting and secret is going to reestablish itself as a value in the same way that punk rockers said, I’m not going to look normal. I’m not going to sing pretty.

Kristen Thompson, who ran Simple Machines with me, shared an album where all the song titles were in Morse code, which of course makes it impossible for any of the algorithms to recommend their songs. There’s no way that this was an accidental choice, and that kind of decision does seem a little bit like an art project or as like a way of getting a different kind of attention because it’s so different from a word where constant self-promotion is just a precondition of being a creator or getting a next job or whatever we have at this moment.

So, I really don’t know how we disentangle those things. Maybe you don’t want to be on LinkedIn, but where do you get your next job? That’s where everyone’s looking. Maybe you don’t want to self-promote on social media, but if you’re going to try to do a tour, more and more often the clubs determine who they book based on numbers of followers.

RC: You’re speaking my language now. These are all problems I’ve been having.

JT: It’s that centralization of attention. I don’t think it has to be that way. We could have chosen a different way or built different kinds of technologies that would’ve allowed us to maintain agency, privacy and diversity… lots of smaller pockets of success coexisting… and we would’ve had more competition in those environments, and we would’ve had accountability because they’d be fighting for your business. It sucks that for the last 20 years, the people who were in charge ignored technology, and then—in my book I talk about it like the stages of grief. There was a very long period of denial and then, you know, bargaining and rage and negotiating, but so many of them still haven’t gotten to the place of acceptance. And when you’re in acceptance, you’re like, “Okay, the world we were in before, it’s over. My partner is dead now. I can’t have another vacation with them. It’s over,” you know? And now I’ve accepted this, and I am in my next life and it’s sad… but acceptance means I can begin to build a real life because anyone that pretends we’re living in the previous world is in denial.

I don’t know if that makes sense, but that’s certainly how I see it.

RC: Oh, it does… When I talked to Ian MacKaye, he mentioned the fact that punk was the last youth movement that used paper, which just struck me as such a brilliant insight that I’d never really thought about. He’s talking about zines and flyers and stuff. What do you think about that idea of paper being punk?

JT: I think paper contains the human gesture in a way that many forms of digital creativity does not. It almost always involves a greater level of scarcity. You could have the gesture of a human image or a human choice in someone who makes digital art, but it’s immediately replicable, you know? So, there’s not that scarcity in the same way—like people trying to create the artificial scarcity through the Bitcoin type stuff and those whatever they were called that everyone was talking about—

RC: NFTs?

JT: Yeah, but there’s something else about the pace of paper. It’s slower. Tsunami’s putting out a box set and Simple Machines putting out a box set with Numero, so I was forced to look at my archives. I have like 50 journals, and I had something like 17 suitcases packed with ephemera and letters—even before punk rock: I have a whole suitcase of all of my junior high school and high school correspondence, and it’s absolutely transformational.

RC: Absolutely.

JT: In almost all of the letters that I received in junior high school and high school people used fake silly names. They drew art on every envelope. They created collages. They were poets. There’s poems in there. There’s pictures in there. We were using every bit of our creativity to communicate with each other. And soooooo much time. These letters took hours. I can barely be bothered to write a full email these days or to listen to a voice message. Our level of attention is so fragile. It’s just destroyed. I had such deep attention, but everything is constantly distracting and pleasing us with little dopamine hits. We’re always jonesing now.

I also think that there was more of a barrier in some ways, too. There’s a privilege barrier. You had to have enough time to write all those letters, or the ability to cobble together a group house and enough part-time jobs that you had enough resources to be able to go on tour. So, when I think of how inexpensive it was to live when I was younger and how expensive it is now, it’s really shocking to me, but aside from that there was also a physical and time barrier to getting things out in the world. There were a lot of great bands that just didn’t have the work ethic to put the 30 to 50 postcards together to send them out to the clubs to try to get shows, because that’s how we got our shows. You wouldn’t waste money on a phone call. You sent a postcard to a club suggesting they might want to book your band without any ability to hear you at all.

RC: This is a whole other world.

JT: Part of what I really liked about working at Ford was we’re funding these brilliant visionaries who are getting the grants. They are the people who do the work, and they should have the platform and the attention to use their brilliant voices and it’s been a privilege to amplify those voices. But it also does mean that except in a few very specific forums, I’ve put my voice away for 16 years, and a part of that op-ed was also about beginning to think about, Well, what does Jenny’s voice sound like,16 years later?

RC: Exactly.

JT: That’s why I’m trying to write a book as well, but it’s really hard to write a book. I don’t know how you wrote nine books.

RC: Well, I’m glad to help in any way that I can.

JT: I mean, what I should be doing is not an interview with you but writing. I’m supposed to be writing every day, and I get to do it a couple days a week.

RC: You and me both!