“One day you might find cause to ask yourself what the limit is to some pain you’re experiencing, and you’ll find out there is no limit at all. Pain is inexhaustible. It’s only people that get exhausted.” — Detective Ray Velcoro, True Detective1

“You’re just generating more pain, more penance for the one sin you couldn’t help commit. The sin of being born.” — Jerry Stahl, Permanent Midnight2

“Pain’s a secret no one keeps.” — Publicist UK, “Levitate the Pentagon”3

“Pain looks great on other people.

That’s what they’re for.” — The Sisters of Mercy, “Wrong”4

If there’s anything that will bring you hurtling back to your body, it’s physical pain, a ready reminder that your physical form is inescapable. Even so, pain is intoxicating. We seek it out. We can’t live without it. It makes us feel alive in a way that nothing else does. Happiness, elation, ecstasy, excitement, contentment—these feelings are elusive and fleeting. Pain is certain and ready at hand whenever we need it.

After a bicycle wreck in the busy streets of Chicago years ago, I spent several weeks in a leg brace and the first two weeks of those on crutches. The experience slowed me down in many ways, not all of which were bad. I’m not recommending cracking a kneecap to get reacquainted with the everyday, but a good jarring of the sensorium might help us all once in a while. Nothing brings reality crashing back in like crashing back into reality.

In addition to my patella, I also broke my phone. The cracking of its screen left it useless for texting or taking pictures. Ironically, the only thing it would do was send (provided I knew or could find the number) and receive calls. I also stopped wearing headphones as my injury already made me an easy mark. These two things—no texting and no headphones—reconnected me with aspects of my days I’d been avoiding or ignoring.

Also, I had to change up my commute. For one thing, I obviously wasn’t able to ride my bike to work, which is what I was doing when I crashed. I wasn’t able to take the train because I lived almost a mile from the closest station, and I couldn’t walk that far on crutches. It should also be noted that there are only a few Chicago Transit Authority train stations with elevators. Stairs were out of the question for a few weeks. This put me on a multiple bus-route commute that took me through parts of Chicago I’d never seen.

Possibly the most important factor that made breaking my kneecap an enlightening experience was sociological rather than technological. Collectively we tend to other the impaired among us. That is, there seems to be a clear delineation between the impaired and the normal; however, if one of us is only temporarily injured, we sympathize, empathize, or pity them.

In the month that I wasn’t texting or listening to music and had a bum leg, I had countless uplifting and informative conversations with people whom I wouldn’t have spoken to otherwise and who wouldn’t have spoken to me for one reason or the other. All of the above made me feel far more connected to my fellow humans than any technology or so-called “social” media.

My smashing my knee into the pavement at the origami triangle fold of traffic that is the intersection of Elston, Fullerton, and Damen in Chicago shoved me out of my comfort zone in several ways. One thing I noticed one day on my temporarily revised, much-longer commute to campus was a lot of needless anger: a man walking by the bus stop, angry at his dog for being a dog; a lady with her children, angry at them for being children; people on the bus, angry about being on the bus; the bus driver, angry about the people on the bus; and on and on. I wasn’t exactly happy that my right patella was fractured in two places, I certainly had good and bad days recovering, and I’m not better than any of those mentioned above, but I tried to smile at everyone, laugh at my fumbling around on crutches, do my work, and generally let others carry the anger. Getting out of your comfort zone doesn’t have to be quite so uncomfortable, but sometimes being forced is the only way for it to happen. It felt like I needed it.

With that said, a physical therapist saw me out hobbling down the sidewalk in Logan Square with my leg brace on one day. He stopped and asked me about my injury with genuine and professional interest. He then informed me that a broken patella is the most painful kind of injury, which, he added, is supposedly why it is the chosen punishment for those late on their loan or gambling payments. I don’t recommend getting behind.

Pain is an early warning system, a physical sign of something larger gone awry.

Illicit Metabolism

“I’ve had minimal drug experiences because of fear,” says the artist Peter Gabriel. “I can trust machines, yet I can’t trust pills… A machine you can always switch off or get out of… whereas when a pill gets hold of your metabolism, you have to ride through.”5 Pain is the counterpoint. You either ride out the pain, or you ride out a drug to relieve the pain. But David Cronenberg reminds us, “We absorb all technologies into our bodies.” Drugs aside, we have to metabolize more and more of our gadgets and gear.

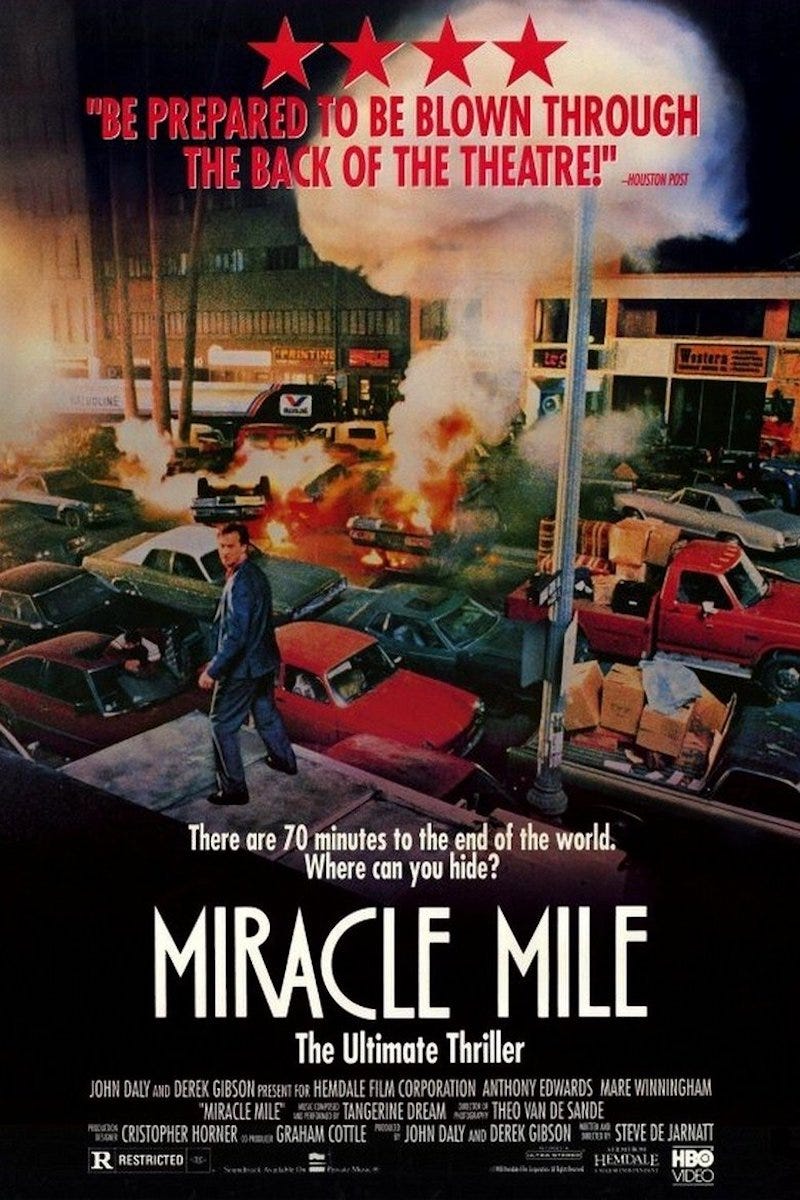

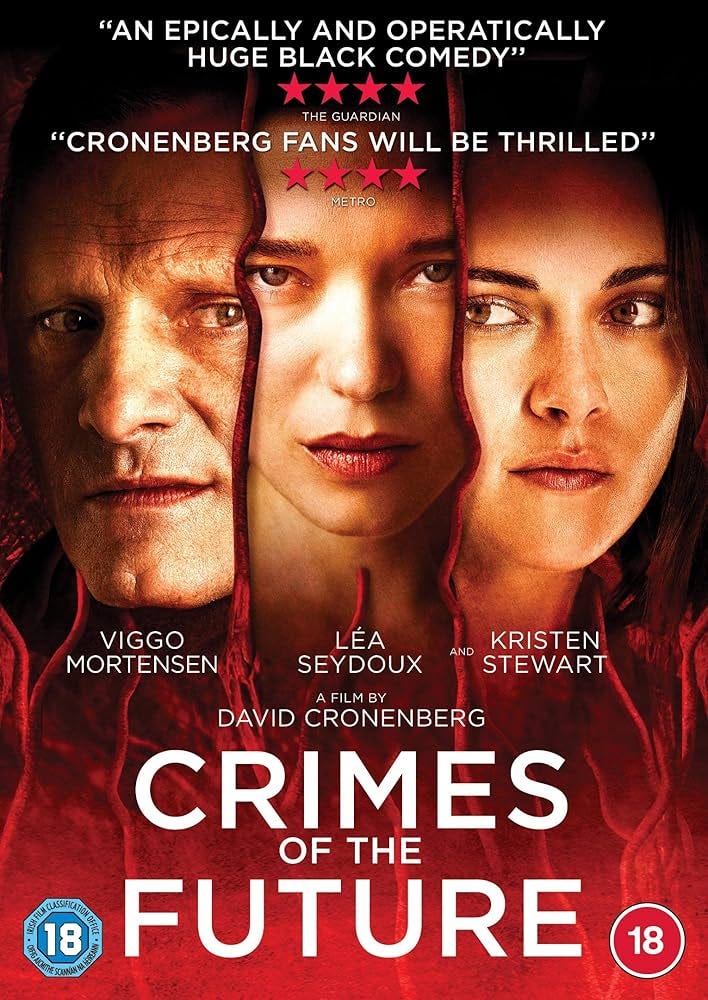

“Body is reality,” reads the catchphrase for Cronenberg’s Crimes of the Future. The writer and director says that the film “is about the crimes committed by the human body against itself.” He says it’s “a meditation on human evolution […] the ways in which we have had to take control of the process because we have created such powerful environments that did not exist previously.”6 He goes on to ponder, “At this critical junction in human history, one wonders — can the human body evolve to solve problems we have created? Can the human body evolve a process to digest plastics and artificial materials not only as part of a solution to the climate crisis, but also, to grow, thrive, and survive?”7

Channeling his former teacher Marshall McLuhan, Cronenberg reminds us, “Technology is always an extension of the human body, even when it seems to be very mechanical and non-human. A fist becomes enhanced by a club or a stone that you throw — but ultimately, that club or stone is an extension of some potency that the human body already has.”8 As Douglas Rushkoff puts it, “Our technologies change from being the tools humans use into the environments in which humans function.”9 Erik Davis adds, “Because the self is partly a product of its communications, new media technologies remold the boundaries of being. As they do so, the shadows, doppelgängers, and dark intuitions that haunt human identity begin to leak outside the self as well — and some of them take up residence in the emerging virtual spaces suggested by the new technologies.”10 I belabor the point here because we don’t tend to think of our technologies as an environment. We don’t tend to think that we’re reshaping ourselves—and our bodies—with every new contrivance. In his introduction to Crash, J. G. Ballard wrote that “what our children have to fear is not the cars on the highways of tomorrow but our own pleasure in calculating the most elegant parameters of their deaths.”11 Warning labels and warding spells: a future defined by risk assessment models and worst-case scenarios.

In The Idiot, Fydor Dostoyevsky wrote,

Now with the rack and tortures and so on—you suffer terrible pain of course; but then your torture is bodily pain only (although no doubt you have plenty of that) until you die. But here I should imagine the most terrible part of the whole punishment is, not the bodily pain at all—but the certain knowledge that in an hour—then in ten minutes, then in half a minute, then now—this very instant—your soul must quit your body and that you will no longer be a man—and that this is certain, certain!

While pain connects us to our own flesh, it isolates us from others. In her book, The Body in Pain, Professor Elaine Scarry writes that to have pain is to be certain.12 To have pain is to be certain of your physical existence, to be certain of your living and being, and to be certain of your mortality. To have pain is to be alone in your body. Scarry writes, “Whatever pain achieves, it achieves in part through its unsharability, and it ensures this unsharability through its resistance to language.”13 She also points out that to hear of another’s pain is to doubt them, thus exacerbating their pain and isolating us, each from another. J. Robbins adds that part of Jawbox’s song “Motorist” was about “imagining being stranded and injured in a place where you suppose nobody will help you.”14

Others might not hurt you on purpose, but they will let you.

“He thought with a kind of astonishment of the biological uselessness of pain and fear, the treachery of the human body which always freezes into inertia at exactly the moment when a special effort is needed.” — from George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four

Mythology of Self

“I’m here to express the pain I feel,” Godflesh’s Justin Broadrick says in a 2023 interview with Decibel Magazine, “and I don’t take much pleasure in that at all.”15 There is a pain inherent to life, the pain of existence. “Pain is also a vehicle of knowledge,” says the poet Ocean Vuong. “It may very well be knowledge itself.”16 To many of us, to be alive is to suffer.

Godflesh has always induced a furious form of suffering on their listeners, and a lot of Broadrick’s music comes from some severe shade of anxiety. After years of self-medicating with drugs and alcohol, which only made it worse, he was diagnosed with autism and PTSD at 52-years old. With that revelation, he was finally able to properly deal with his mental health, decades of compounded pain eased with new tools for coping and care.

“I’ve spent a lifetime trying to please everyone, to make myself feel comfortable,” he says, “a lifetime of not doing things because I’m uncomfortable. Now I’m not masking it so much anymore.”17 On “Nero” from 2023’s hip-hop beat-infused Purge, he barks, “Restrain yourself/ Betray/ Your needs,” and on “Land Lord” he says, “Bad seeds/ Own you/ Shape you/ Slay you/ Control/ Divide/ Enslave/ Destroy.”18 If ever his lyrics were masking his discomfort, they certainly aren’t anymore. Bassist Benny Green adds, “Our general abhorrence at the monstrous injustices humans have always inflicted on each other still impacts us to this day. We’d both quite happily hide away in a remote forest or cave in order not to have to deal with the horrors of mankind.”19 He finds solace in the sonorous: “For me, music, sound, tone, whatever you want to call it,” he continues, echoing Robert Fludd’s idea of a celestial monochord, “is the single most powerful and liberating thing there is, and the whole universe exists through vibrations and waves, music included.”20 Call it Godflesh, an all-encompassing energy that connects us all, each to another and beyond.

Notes:

1 Nic Pizzalatto [writer], True Detective (New York: HBO, 2014).

2 Jerry Stahl, Permanent Midnight (Port Townsend, WA: Process, 1995).

3 Publicist UK, “Elevate the Pentagon,” from Forgive Yourself [LP] (Los Angeles: Relapse, 2015).

4 The Sisters of Mercy, “Wrong,” from Vision Thing [LP] (Los Angeles: Elektra, 1990).

5 Quoted in Daryl Easlea, Without Frontiers: The Life and Music of Peter Gabriel (London: Overlook Omnibus, 2014), 152.

6 Quoted in Angel Melanson, “’A Meditation on Human Evolution’ Crimes of the Future Redband Trailer Is Here!” Fangoria, May 6, 2022.

7 Ibid.

8 Quoted in Clark Collis, “Kristen Stewart Gets the Body Horror Treatment in the New Teaser for David Cronenberg’s Crimes of the Future,” Entertainment Weekly, April 14, 2022.

9 Douglas Rushkoff, Team Human, New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 2019, 52.

10 Erik Davis, “Recording Angels: The Esoteric Origins of the Phonograph,” in Rob Young (ed.), Undercurrents: The Hidden Wiring of Modern Music (pp. 15-24), London: Continuum, 2002, 17-18.

11 Quoted in Paul March-Russell, “How writing about JG Ballard’s most controversial novel helped me cope with becoming a single parent,” The Independent, September 22, 2024.

12 Elaine Scarry, The Body in Pain (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), 7.

13 Ibid., 4.

14 Email to the author, March 22, 2025.

15 Quoted in Daniel Lake, “Long May I Dream These Nightmares,” Decibel Magazine, July 2023, 56.

16 Quoted in Sharon Salzberg, “Why Buddhist Poet Ocean Vuong Practices a Death Meditation,” Tricycle, September 3, 2022.

17 Quoted in Lake, “Long May I Dream These Nightmares,” 58.

18 Godflesh, Purge [LP]. (London: Avalanche Recordings, 2023).

19 Quoted in Lake, “Long May I Dream These Nightmares,” 60.

20 Ibid.