Like birthdays, the end of the year always brings about a recounting of the previous twelve months. We reassess our existence every year, every ten years, every one hundred… Human and technological movements are cyclical. Heraclitus once posited that generational cycles turn over every thirty years. By that metric, the personal computer revolution has run its course, and with it, the cyberpunk genre. Running its course doesn’t mean it’s over. It means it has been assimilated into the larger culture. What was once weird and wild is now a normal part of the world in which we live.

In his autobiography, Nested Scrolls (Tor, 2011), Rudy Rucker tells the story of catching the cyberpunk wave just as it was swelling toward the shore. Rucker already had two science fiction novels out, a third in the pipe, and was out to change the genre with a vengeance. He’d won the first Philip K. Dick Award in 1982 just after Dick died, and met up with the reigning crop of the new movement. “I started hearing about a new writer called William Gibson,” he writes. “I saw a copy of Omni with his story, ‘Johnny Mnemonic’. I was awed by the writing. Gibson, too, was out to change SF. And we weren’t the only ones.” Around the same time, Bruce Sterling was publishing an SF zine called “Cheap Truth.” Rucker continues, “Reading Bruce’s sporadic mailings of ‘Cheap Truth’, I learned there were a number of other disgruntled and radicalized new SF writers like me. At first Bruce Sterling’s zine didn’t have any particular name for the emerging new SF movement — it wouldn’t be until 1983 that the cyberpunk label would take hold.” It was in that year that Bruce Bethke inadvertently named the movement with the title of his short story “Cyberpunk.” In this revolution, the names Rucker, Gibson, and Sterling were loosely joined by John Shirley, Greg Bear, Pat Cadigan, and Lew Shiner.

While cyberpunk sometimes seems a definitively 1980s affair, it was often ardently so at the time. It was post-punk and pre-web, yet wildly informed by the onset of the personal computer and the promise of the internet, which marks the genre in sharp contrast to its galaxy-hopping, alien-invaded forebears. Rudy Rucker is the bridge from Dick-era, drug-induced paranoia to Gibson-era, network-minded paraspace. He was around early enough to be a Dick fan before Dick died, but noticeably older than the rest of the cyberpunk crew. Nested Scrolls secures his place joining the generations of the genre.

It’s not all computer-generated virtual worlds though, Rucker has had a storied career as both an author of science fiction and nonfiction, as a college professor, and as a software developer, all of which inform each other to varying degrees, and all of which inform Nested Scrolls, making it an engaging narrative of high-science, high-tech, and high times. Cyberpunk’s not dead, it’s just normal now.

—————

Illustrating the initial disjointedness of the genre, here’s the 1990 Cyberpunk documentary, directed by Marianne Trench:

References:

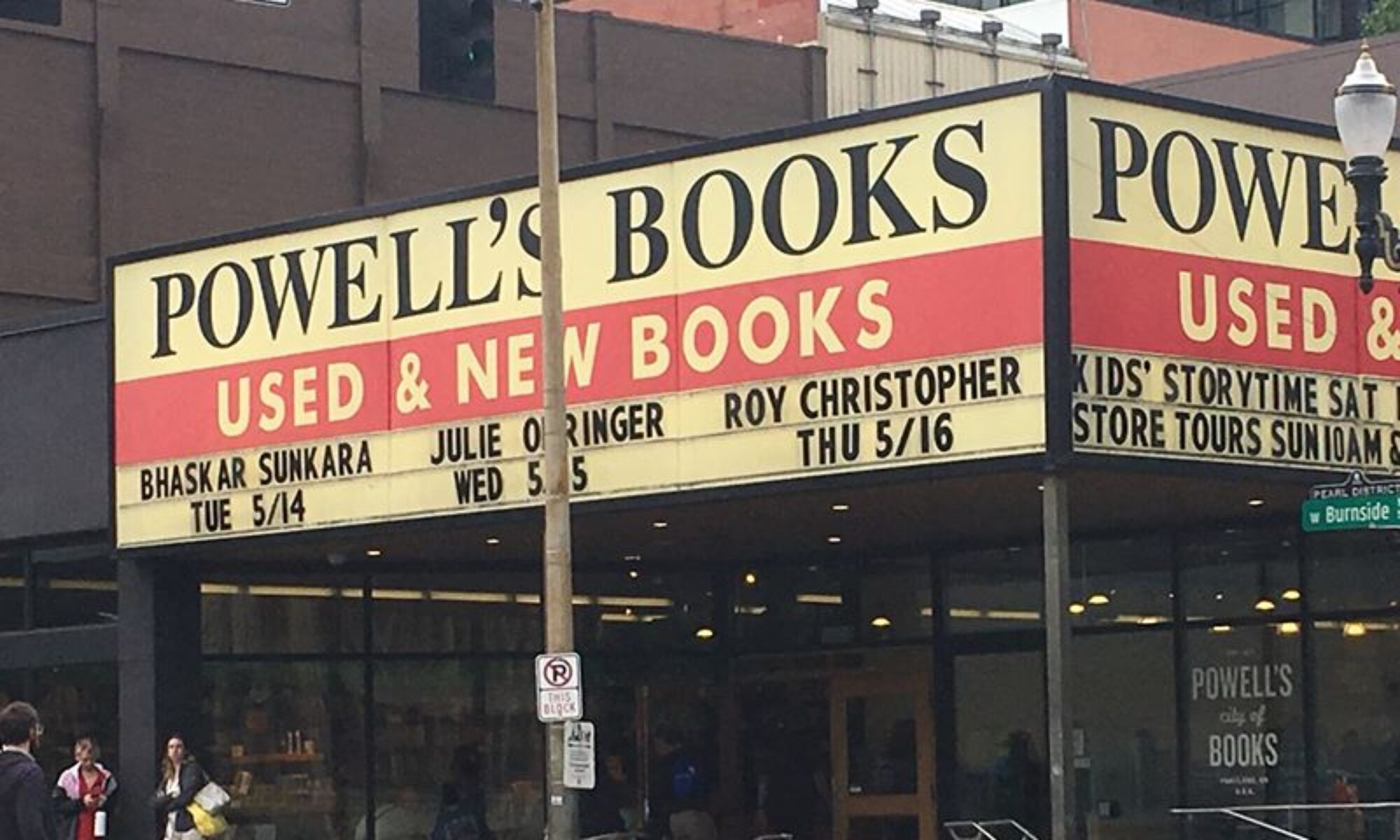

Georgoulias, Tom. (2007). Rudy Rucker: Keeping it Transreal. In Roy Christopher (Ed.), Follow for Now: Interviews with Friends and Heroes. Seattle, WA: Well-Red Bear.

Heraclitus. (2001). Fragments. New York: Penguin Classics.

Rucker, Rudy. (2011). Nested Scrolls: The Autobiography of Rudolph von Bitter Rucker. New York: Tor.

Rucker, Rudy. (2011, December 6). The Death of Philip K. Dick and the Birth of Cyberpunk [Book excerpt]. io9.com.

Trench, Marianne (Director) & von Brandenburg, Peter (Producer). (1990). Cyberpunk. Mystic Fire Video.

Notorious (Fox Searchlight, 2009) does a serviceable job of telling Biggie’s story from a fan’s perspective. To be fair, Voletta Wallace (Biggie’s moms) and Sean Combs (his A&R rep, mentor, and friend) are executive producers, so investigative reporting this isn’t. Also serviceable is Jamal Woolard’s depiction of Biggie. It’d be dead-on if it were based on mannerisms alone (everyone in this movie nails the nonverbals), and if Anthony Mackie’s performance as Tupac Shakur wasn’t so fresh (though it is jumped off by a “dear stupid viewer” scene in which he’s unnecessarily introduced by name several times). The studio scene that started the so-called coastal feud between Biggie and Tupac, Bad Boy and Death Row records — in which Tupac is shot several times and in the confusion blames Biggie and the Bad Boy crew — is written and filmed in a perfectly chaotic manner. You feel like a witness to the jumbled madness. Biggie’s coincidentally tying up all of his personal loose ends on the eve of his death on the other hand…

Notorious (Fox Searchlight, 2009) does a serviceable job of telling Biggie’s story from a fan’s perspective. To be fair, Voletta Wallace (Biggie’s moms) and Sean Combs (his A&R rep, mentor, and friend) are executive producers, so investigative reporting this isn’t. Also serviceable is Jamal Woolard’s depiction of Biggie. It’d be dead-on if it were based on mannerisms alone (everyone in this movie nails the nonverbals), and if Anthony Mackie’s performance as Tupac Shakur wasn’t so fresh (though it is jumped off by a “dear stupid viewer” scene in which he’s unnecessarily introduced by name several times). The studio scene that started the so-called coastal feud between Biggie and Tupac, Bad Boy and Death Row records — in which Tupac is shot several times and in the confusion blames Biggie and the Bad Boy crew — is written and filmed in a perfectly chaotic manner. You feel like a witness to the jumbled madness. Biggie’s coincidentally tying up all of his personal loose ends on the eve of his death on the other hand…

![Mogwai live [photo by Leif Valin]](http://roychristopher.com/wp-content/uploads/mogwai-live.jpg)