In his 1995 book, Being Digital (Vintage), Nicholas Negroponte drew a sharp and important distinction between bits and atoms, bits being the smallest workable unit of the digital world, and atoms being their closest analog (no pun intended) in the physical world. In the meantime, this distinction has become more and more important as our world becomes increasingly digital or reliant on digital technologies.

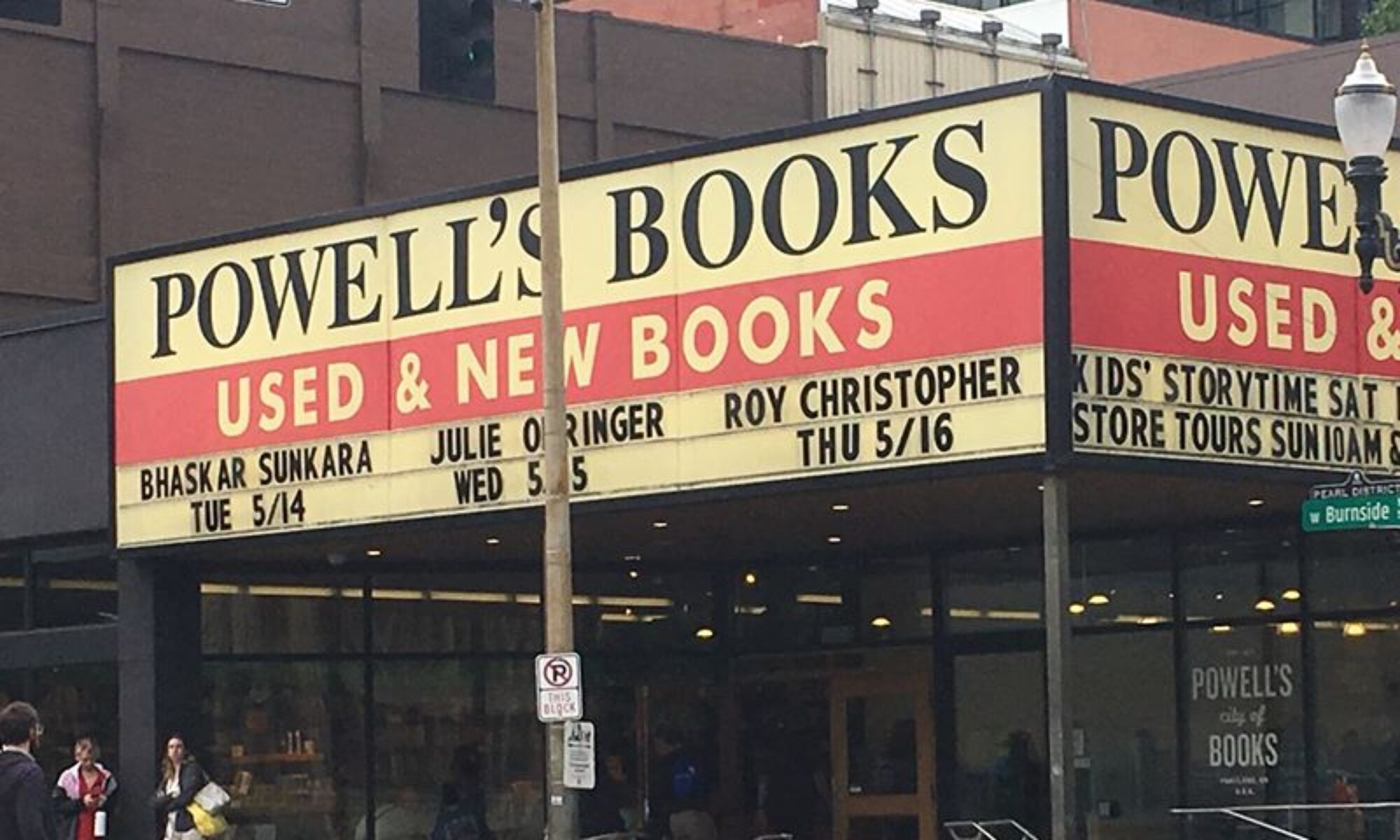

As an over-simplified example, shelf space in a regular “bricks and mortar” bookstore is limited, but online it isn’t. In order to pay its rent and stay in business, a physical bookstore has to carry books that sell at a faster pace than an online store, which can afford to carry books that sell less often. The latter is called “the long tail,” and it’s how Amazon was able to stake its claim as “The World’s Largest Bookstore” and eventually to expand into every other product line one can put in a box or an inbox. When it comes to purely digital artifacts and products (e.g., digital file sharing, music downloads, ebooks, etc.), the power law on which the long tail is based isn’t truncated (as it is eventually in the Amazon example, and sooner in the traditional bookstore example).

As an over-simplified example, shelf space in a regular “bricks and mortar” bookstore is limited, but online it isn’t. In order to pay its rent and stay in business, a physical bookstore has to carry books that sell at a faster pace than an online store, which can afford to carry books that sell less often. The latter is called “the long tail,” and it’s how Amazon was able to stake its claim as “The World’s Largest Bookstore” and eventually to expand into every other product line one can put in a box or an inbox. When it comes to purely digital artifacts and products (e.g., digital file sharing, music downloads, ebooks, etc.), the power law on which the long tail is based isn’t truncated (as it is eventually in the Amazon example, and sooner in the traditional bookstore example).

Chris Anderson admittedly didn’t invent the idea (Jeff Bezos for one has been making millions with it for years), but no one else has covered it like he has in his book. The Long Tail: Why the Future of Business is Selling Less of More (Hyperion, 2006) is the concept shot from every angle, through every available lens. The idea is that blockbusters, hits, best sellers form “the short head” of the graph, and the niche items, cult phenomenon, lesser sellers form “the long tail.” Our culture is moving down the tail (i.e., it has become “niche-driven” as opposed to hit-driven) and off the shelf (online as opposed to in the store). Most retail stores only have room to carry items in the short head, while online “etailers” can carry items further down the tail. And when it comes to digital products, shelves are no longer an obstacle, in more ways than one.

When products move from shelves to databases, the way they can be organized changes. Everything is Miscellaneous: The Power of the New Digital Disorder (Times Books, 2007) is David Weinberger’s take on Web 2.0’s tags and folksonomies, set in contrast to objects in physical space (bits vs atoms). “Orders of order” he calls them. Items on shelves are limited by the rules of the physical world. Items in a database are not. The former can be filed in one category, on one shelf, in one place (the first order of order). The latter can be searched, browsed, alphabetized, tagged — all at the same time (the third order of order). These orders of order also apply to encyclopedic information — Wikipedia’s bits as opposed to Encyclopedia Britannica’s atoms — and the way it is created.

When products move from shelves to databases, the way they can be organized changes. Everything is Miscellaneous: The Power of the New Digital Disorder (Times Books, 2007) is David Weinberger’s take on Web 2.0’s tags and folksonomies, set in contrast to objects in physical space (bits vs atoms). “Orders of order” he calls them. Items on shelves are limited by the rules of the physical world. Items in a database are not. The former can be filed in one category, on one shelf, in one place (the first order of order). The latter can be searched, browsed, alphabetized, tagged — all at the same time (the third order of order). These orders of order also apply to encyclopedic information — Wikipedia’s bits as opposed to Encyclopedia Britannica’s atoms — and the way it is created.

In Infotopia: How Many Minds Produce Knowledge (Oxford, 2006), Cass R. Sunstein continues some of the work he did in Why Societies Need Dissent regarding deliberation, group polarization, and emergent knowledge. The most obvious and most successful example is Wikipedia. Whereas mindless mobs wait at the bottom of many collaborative slippery slopes (see a sharp antithesis to Wikipedia at Urban Dictionary), Wikipedia is frighteningly accurate. My friend and colleague Tim Mitchell proposed a great test of Wikipedia’s success: If you doubt the site’s aggregate knowledge, check its information against something you do know, as opposed to something you don’t. Sunstein’s book goes a long way to explaining the ins and outs of why collaborative filtering might provide the best method for knowing things.

In Infotopia: How Many Minds Produce Knowledge (Oxford, 2006), Cass R. Sunstein continues some of the work he did in Why Societies Need Dissent regarding deliberation, group polarization, and emergent knowledge. The most obvious and most successful example is Wikipedia. Whereas mindless mobs wait at the bottom of many collaborative slippery slopes (see a sharp antithesis to Wikipedia at Urban Dictionary), Wikipedia is frighteningly accurate. My friend and colleague Tim Mitchell proposed a great test of Wikipedia’s success: If you doubt the site’s aggregate knowledge, check its information against something you do know, as opposed to something you don’t. Sunstein’s book goes a long way to explaining the ins and outs of why collaborative filtering might provide the best method for knowing things.

Mark Hurst’s Bit Literacy: Productivity in the Age of Information and E-mail Overload (Good Experience, 2007) approaches the infoglut from more of a self-help angle, proposing an ambitious plan for getting things done and getting things organized in the digital deluge. It’s not quite the panacea it purports to be, but useful ideas abound. Finding signal in the noise — especially in the noise of your own email, photos, files, to-do lists – is what bit literacy is all about.

Mark Hurst’s Bit Literacy: Productivity in the Age of Information and E-mail Overload (Good Experience, 2007) approaches the infoglut from more of a self-help angle, proposing an ambitious plan for getting things done and getting things organized in the digital deluge. It’s not quite the panacea it purports to be, but useful ideas abound. Finding signal in the noise — especially in the noise of your own email, photos, files, to-do lists – is what bit literacy is all about.

As bandwidth increases, Negroponte’s observation from over a decade ago is finally showing its impact. The distinction between bits and atoms is an important one, and perhaps more important than we previously realized, whether we’re trying to find something or just find something out.