You’ve seen them: “Andre the Giant has a Posse” stickers, “Obey Giant” posters, Andre’s face covering entire sides of buildings. You’ve seen them and you’ve wondered what it was all about. And once you found out, perhaps you wondered why.

You’ve seen them: “Andre the Giant has a Posse” stickers, “Obey Giant” posters, Andre’s face covering entire sides of buildings. You’ve seen them and you’ve wondered what it was all about. And once you found out, perhaps you wondered why.

Nearly the entire world has unknowingly fallen prey to Shepard Fairey’s phenomenological street-media experiment. Long-time friend Paul D. Miller recently described Shepard’s postering activities as “obsessive.”

Using an image of the late, large (7’4″ 520 lbs.) wrestler-cum-actor Andre the Giant’s face, Fairey has slowly spawned an underground cult sensation. As he wrote in 1990, “The first aim of phenomenology is to reawaken a sense of wonder about one’s environment. The Giant sticker attempts to stimulate curiosity and bring people to question both the sticker and their relationship with their surroundings. Because people are not used to seeing advertisements or propaganda for which the product or motive is not obvious, frequent and novel encounters with the sticker provoke thought and possible frustration, nevertheless revitalizing the viewer’s perception and attention to detail.” Adopting and adapting philosophy from Martin Heidegger, Marshall McLuhan, Guy Debord, and Hakim Bey, Shepard Fairey has caused many a reawakening, and established himself as one of the leading designers of visual identity working today.

Teaming up with fellow street artist Dave Kinsey, Fairey formed Black Market, (BLK/MRKT). Here they bring their often edgy, experimental design attitudes to the corporate world, stating “Rather than bringing the underground to the surface, Black Market, a visual communication agency, works to blur the distinctions, to attack everything with the same.” And they do. Their client list includes heavies like Mountain Dew, Earthlink, Levi’s, Sprite, Netscape’s Mozilla project and Madonna’s Maverick Street imprint, among others, as well as smaller firms like Ezekiel Clothing, DC Shoes (who actually made a Fairey-designed line of Giant shoes for a while), Strength Skateboard Magazine, logos for Doug Pray’s DJ documentary Scratch, and countless others.

A colleague of mine recently commented that he regards the Giant sensation as a “well-managed fluke.” As pejorative as that might sound — with his Giant clothes, snowboards, skateboards, a forthcoming book project, and a CD project on the way, not to mention his posters and the ubiquitous “Andre the Giant has a Posse” stickers — I doubt Fairey would disagree.

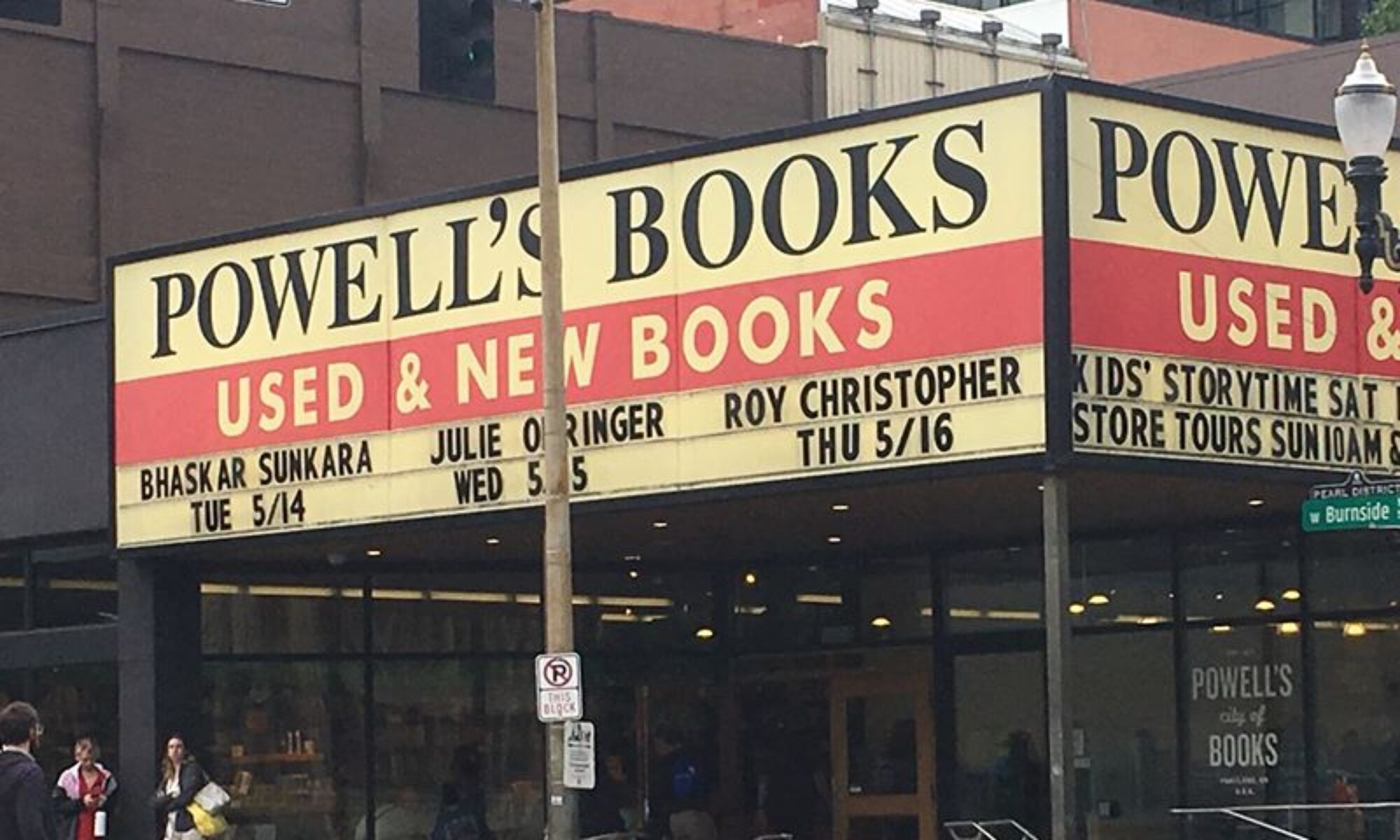

Roy Christopher: On the surface your Giant campaign is seemingly intentionally pointless, but under the absurdity, what is the point?

Shepard Fairey: The campaign started off as a joke and I purely by accident noticed, after putting stickers around as a meaningless joke, that when something exists for reasons that are not obvious, application and context become the meaning and, therefore, how it relates to the things around it. Bringing these surrounding elements into question, purely by contextual association — sort of like, “well, it’s next to a bunch of band stickers, so it must be a band.” In this process, band stickers as a medium for communication to a greater or lesser degree, will be examined simultaneously with my sticker.

The sticker did not start as anything profound, but as I observed peoples reactions to it, I saw the potential to use it as a devise to stimulate a Rorschach test-like response from people and ultimately create a dialog about the process of imagery absorption. Plus, I was just trying to get something out there that signified my existence, even anonymously.

RC: One of the most profound and politically powerful aspects of street art (graffiti, postering, stickering, etc.) is the reclamation of public space. Do you see yourself as a proponent of this movement?

SF: Absolutely. Another facet of the project is to call into question the control of public space. As taxpayers, we own the public space and we pay the politicians salaries. We are their bosses, not the other way around; however, the politicians favor the powerful businesses who would obviously prefer that there were no other visual noise distracting from their paid advertising and signage. We basically live in a spectator democracy and one of the few ways to actually be heard is through street art. I don’t just mean a political agenda, in the traditional sense. Street art itself is political, in that it is a “medium is the message” act of defiance. I’m not an anarchist, so I feel that street art should be integrated in a way that is respectful of private property. Not that paid advertising has any kind of ethics; they get away with whatever they can, and billboards encroach on the whole visual horizon. My feeling is that it’s all or nothing. Either no billboards and no street art, or there’s advertising and some tolerance for street art and other low budget grassroots promotions. That’s the only way to be democratic.

RC: You’ve been arrested and even beaten up by police for simply engaging in your art form. How do you justify what you do in the face of this oppression?

SF: I probably wouldn’t be doing what I am doing if there weren’t an element of oppression. I guess I feel like I can’t be belted into submission when I feel that my project helps initiate a dialog about the use of public space and possibly drags some of the silent majority out of the woodwork to voice their opinion on the subject. If you make it past one arrest and still have it in you, you’ll probably be doing it no matter what. I’m diabetic and have gotten in trouble in jail when the cops wouldn’t give me my insulin, so I recently got a “diabetic” tattoo, as a precautionary measure, in case I ever passed out in jail. I don’t consider myself a symbol or a martyr, I just don’t want to give in to the system.

RC: The Obey Giant campaign has raised awareness to our society’s overwhelming brand consciousness. As memetic devices, the stickers and posters have been wildly successful in spreading this metamessage based primarily on absurdity. Was this your original intent, or did it all just get out of hand? Or both?

SF: It started off innocently enough, but I quickly became obsessed with the idea of producing art that competed with and distracted from heavily funded advertising campaigns on a shoestring budget. As a creative person, I was excited by all the different methods I could use to virally spread my campaign. After many years of hard work and grassroots proliferation it had a life of its own and became its own juggernaut that I was avidly fueling but not solely propelling.

RC: You move seamlessly from wheat-paste street campaigns to creating corporate identities and back. What do you say to the detractors who claim that when you cross that line, you undermine the legitimacy of your work?

SF: I tell them, if they’d send me some nice donations to pay for all of my stickers and posters, then I would never have to do corporate work. I also tell them if they still live at home or have never had their own business or a project as ambitious as mine, then they are really in no position to be judgmental. Seriously though, the point of my campaign is not to point the finger at corporations and accuse them of being evil. We live in a capitalist society, companies exist to try to profit. The point of my campaign is to encourage consumers to be more discriminating and not let themselves be easily manipulated by companies and their advertising. The money that I make from doing corporate work allows me the freedom to do other things that I want to do, such as, travel around to different cities to put my stuff up and to make more posters, stickers, and stencils all the time. There is stuff for sale on my website, but there is also a network of people that I send stuff out to free. This is very expensive. The other thing is that I’d like to make corporate or mainstream companies not suck as hard, by doing some artwork for them that doesn’t insult the consumer. I look at it like “wouldn’t it be great if you could turn on the radio and hear great songs even on the Top-40 station?” I know this philosophy won’t appeal to the elitist who thinks it’s cool to be marginalized and special and into the hip things that no one else knows about, but I’m a populist, and I think that attitude is very immature.

RC: Who do you find challenging in the design world these days? Who’s pushing the limits? Who’s work do you like?

SF: I like people who blur the line between fine art and graphic design. People like Stash and Futura, Evan Hecox, Dave Kinsey (my partner), WK Interact, Haze, Rick Klotz from Fresh Jive, Ro Starr, Ryan McGinness, Kaws, Twist (he is more of a painter/graffiti artist), ESPO — too many to name. There are a lot of people who have grown up with a lot of advertising and sensory over-stimulation from video games and MTV, who are making very smart and engaging art and graphics. I don’t know what to call this movement, but Tokion Magazine‘s next issue is focusing on it. I really think the changing of the guard in the art and design world is beginning.

RC: What’s coming up for you and BLK/MRKT?

SF: I have a book of my street art installations coming out through Gingko Press and Kill Your Idols (the guys who made the FuckedUp + Photocopied punk rock flyer book). I also have a CD compilation called The Giant Rock ’n’ Roll Swindle (Fork In Hand, 2002), coming out with special packaging, featuring songs by Modest Mouse, the Hives, Jello Biafra, the International Noise Conspiracy, the Bouncing Souls, etc. It also, has an enhanced CD ROM segment with my poster images, video, and stencil instructions. I’m really excited about that because punk rock really stimulated my interest in art and politics. Besides that, we just moved to Los Angeles and opened a gallery in our new space. We are doing shows with a lot of the artists that I mentioned above. I’m also constantly working on poster designs and stuff for the clothing line. Not enough hours in the day, I tell ya. I got married too, and my wife rules, so I’m trying not to take her for granted.