Poetry is one of our most radically subjective communication media. One person’s transformative verse is another’s cliché. We struggle to understand each other, yet we quickly tire of the same old words and phrases.

Meanings are malleable. Language bends and breaks under the stress of unintended use, abuse, or overuse. Like machine parts pushed past their limits, cogs stripped bare of their teeth, the words we use wear out, weakening the culture that carries them and our connections to each other.

The barriers to appreciation are also unreasonably high. Being into poetry is a strange burden to carry. Never mind being a poet.

Danika Stegeman LeMay is a poet. She bends words and molds phrases, creating and transforming meanings. I’ve been reading her work and corresponding with her about it for a couple of years now. With her new book, Ablation, coming out next month, and a few other projects cued up behind it, I knew a more formal interview was well past due.

Roy Christopher: How did you get started writing in the first place?

Danika Stegeman LeMay: Oh, the usual: by listening to The Smashing Pumpkins’ Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness. Around the time that record came out, I had a really great 7th grade English teacher. I was painfully, cringingly shy until I was about 17 years old. Apparently my book reports or whatever were good, or the teacher understood I needed an outlet that allowed me to be quiet. There was some kind of writing conference for middle schoolers in the state of Minnesota, and the teacher got to choose one student and he chose me. I spent the day learning about writing at a local college and they gave us all journals to write in at the end. I think the theme of the conference was peace (very 1990s) and the journal had little zen quotes about being peaceful in it.

Instead of writing about peace I wrote what amounted to a very, very bad Smashing Pumpkins “song.” It was my first poem. More poems followed, and what’s really charming to me about that journal is that we weren’t quite really in the word-processing era yet. Like, if you wanted to save a draft, you had to have a floppy disk. So I’d write poems by hand and then re-write them by hand to make a revision. I re-copied so many poems in slightly different variations. Along with collage, repetition is an interest that’s captivated me across time, so the fact that I wrote and re-wrote these pieces as my youngest poet self is sort of heartwarming.

RC: When did you know it was going to be a passion or a problem?

DSL: I think I knew it was going to be a passion/problem by the time I was getting ready to graduate from undergrad. I was trying to decide if I’d apply for MFAs or do something “practical” like law school. I was dating someone who was getting his MFA in printmaking at the time, and I asked him what he thought. He said to me, “you can’t just not practice your art because it’s easier.” Because it’s not easy to love something and to want to pour all of your energy into it when you can’t make a living doing it. There will always be interruptions so you can afford to eat sandwiches or pay an ungodly amount for rent or see a doctor when you’re sick (but only like, insanely sick, or it’s probably not worth the cost). The number of times I’ve thought “I wish someone would pay me to write poetry.” But creating art out of love, desire, a kind of inner pull/force that I feel but can’t quite articulate has its own intrinsic value that has nothing to do with money. So most of the time I’d call it a passion, a “strong and barely controllable emotion,” rather than a problem.

When I think about writing as a “problem,” I think about “problem” more in the sense of physics or mathematics: an inquiry or investigation, rather than a matter of harm. It seems to me that my poetic projects and I unfold together; we figure out what forms we’ll take across time and space. It’s a spiral of questioning, a call and response.

RC: You’re quite prolific on social media, especially with your #lineaday series of posts. I always find that a pursuit becomes something different than I originally intended when pushed in such a way. Have you found out anything from the practice of posting daily?

DSL: I’ve come to appreciate the #lineaday posts I make as stories daily on Instagram in several ways. For one, it’s a way to exercise a muscle. Whether any of those lines get put into a larger piece or not, they’re a dedication to language that I make each day, and I consider writing a line a day a similar action to my daily yoga and meditation practices. It’s a way to honor and shape the mind and voice by way of patterning and ritual. Writing a line per day is also a way to trick my mind into releasing anxiety around the generative act. I don’t pressure myself to be brilliant, a line is a line and doesn’t have to be final. An Instagram story disappears after 24 hours. Like anything, it exists and it passes away. It reminds me life changes and is impermanent. Though of course I do save the lines in a Google doc… It’s material to use or not use in the future. It gives the generative process a spirit of play.

All these words I’ve piled up have softened and washed away some of my anxiety around having a blank page in front of me. I have this stockpile of material to refer to and riff off of. And I do often refer to that pile. During the pandemic, I took an online class about collage-based writing called “In Pieces” with Joshua Bridgwater Hamilton. I can’t remember what the reading was, but we read a piece by Clarice Lispector. She talks about how she’d write snippets whenever they came to her–on scraps of paper, napkins, etc. and save and pile them up. Eventually, she’d wake up very early in the morning and work for hours, poring over these pieces and pulling them together. She said something about how that’s when the time and the energy and the struggle comes in, constructing the work into a whole entity from these pieces. In a way what she’s doing is collaging herself. I’m also a collagist at heart. I like to pull materials together, to consider juxtapositions and unexpected symmetries. Even when I started writing poems as a teenager, often what I was doing was collage, even if I didn’t realize or understand that’s what I was doing.

RC: I find the same. Sometimes it’s just a juxtaposition—rubbing two things together to see what comes of their intersection—and sometimes it’s a whole pile of things that come together and transform into something else.

DSL: Transformation is, in my opinion, one of the most magical things we do. We look at a cloud and name it tree. Even a juxtaposition is a pile of transformation. What else would it be? The cosmos is vast and the one thing we know for sure is that it changes things. We work with materials on an infinitesimal scale in the same ways that they work on an infinite scale.

RC: Tell us about your latest project for 11:11, Ablation.

DSL: Ablation is a book I wrote about my mom’s death, becoming a mom to a daughter, inherited trauma, and how to acknowledge pain and loss while accepting it and realizing it exists alongside joy. In these liminal places of death and birth, we see perhaps more clearly that we are a line: fear and love, void and form, grief and acceptance, chaos and control, are two sides of the same door, and we’re the door. The book moves through many forms to arrive at realization and acceptance. It contains images I’ve cut apart, re-assembled, and sewn. It reckons with images of the past that haunts it, and by it, I suppose I mean me. After my mom died, I found like 8 rolls of film from the early and mid-1990s that she’d never developed in her closet, while I was going through her things trying to decide what to keep and what to let go of. I developed the film, because that’s the kind of person I am. I will follow things to completion.

The images the photo lab was able to develop are haunting for a couple of reasons: they’re literally fucked-up—if you leave film to sit for years, you get double exposures, strange colors, dark fog, dust motes, and flares of light. They’re also fucked-up because part of the reason my mom never developed them is that they’re mostly photos my brothers and I took the summer after my stepdad died in a head-on collision with a semi-truck when he was driving home from work when I was 13. He fell asleep at the wheel. It completely wrecked my mom, who’d had a painful life anyway, and had struggled with depression and other mental illnesses without diagnoses or any sort of medical help her entire life.

The photos themselves are haunted. You can feel our pain in them. Writing, collaging, taking a thing apart to understand it, rearranging it into something like hope, like future, like presence, and taping it back together is my way of coping with the world as I find it: both terrifying and radiant. The process of writing the title sequence, “Ablation,” which is a long, tightly-wound sequence of mirror cinquains, was that sort of collaging myself process I was talking about earlier. I originally wrote that sequence on postcards, but the form didn’t quite feel right. When I arrived at the mirror cinquain, I worked and re-worked and carved and threaded the words into place. The other poems in the book either attempt to lean into form, as “Ablation” does, or into chaos. Both needed to be present.

This is a book I had to write to continue existing after the sudden and catastrophic loss of my mom. It’s a place where I can leave things, so I can move forward and create a better environment for my daughter. “Ablation” means three compelling and wildly diverse things: evaporation of ice from a glacier, surgical removal of tissue from a body, and the way a spacecraft or meteorite sheds material in the atmosphere. At its root, the word means “taking away.” Ablation is, by nature and necessity, much more vulnerable than my previous work. I had to learn to be vulnerable as a person while writing it. I feel that vulnerability is one of the book’s strengths, and I hope that its presence might be helpful to others moving through similar corridors.

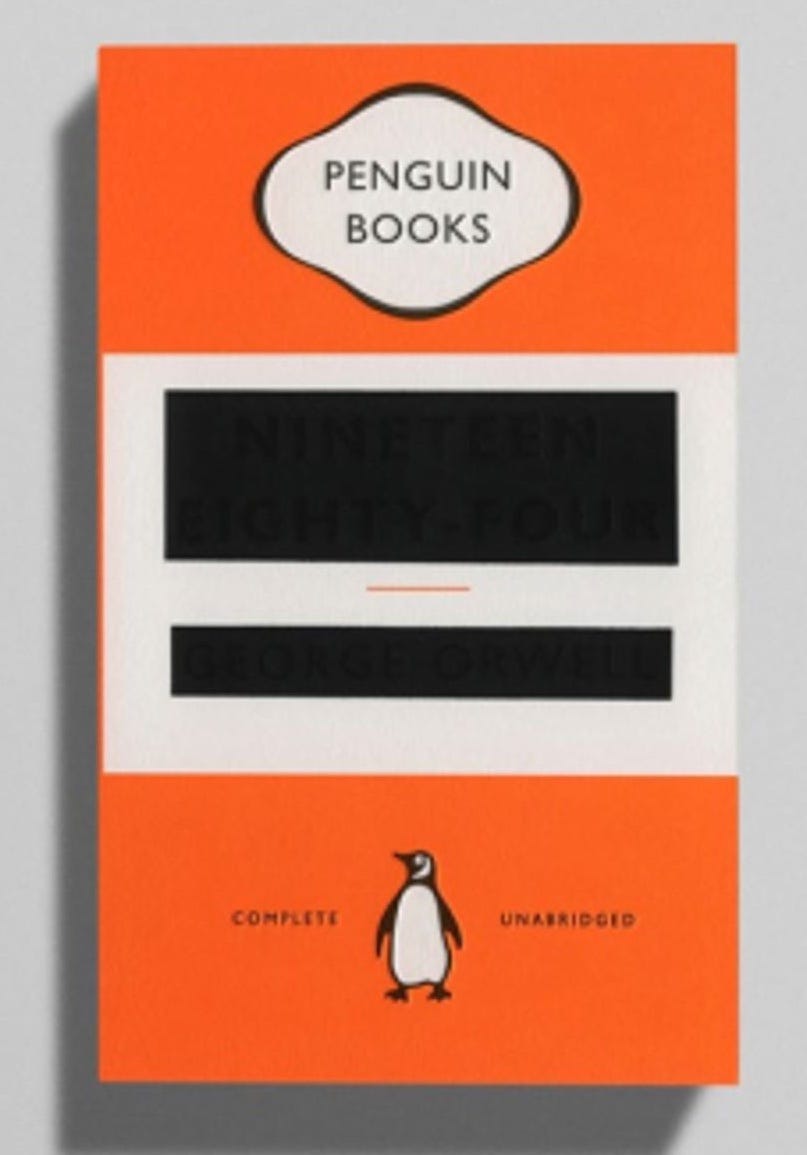

RC: What can you tell us about how your erasure project, GOD IS IN THE MALL, came about and your possible plans for its publication?

DSL: GOD IS IN THE MALL (GIITM) is actually the first full-length manuscript I finished. I wrote it alongside Pilot (Spork Press, 2020) and actually finished it before I finished Pilot. It’s an erasure of a book called God Is in the Small Stuff for the Graduate, which was given to me by evangelical Christian relatives when I graduated from high school. I started circling words in pencil probably around 2006 or so. I got stuck pretty quickly, because the end of every chapter has a list of bullet points about how “God is in the small stuff” for the theme of that particular chapter. And I was like “what am I going to do with these lists?? It’s impossible to erase them in a productive way and make it a poem.” Years later, in probably 2014, I was riding the bus to work and had the idea to cut up a directory of the Mall of America and paste the names of the stores into the list parts of the chapters. So a bullet point that said “You can’t stand up to the devil unless you kneel before God” became “You can’t stand up to the devil unless you kneel before Nordstrom Rack.” And it went pretty quickly after that.

When I’d finished penciling in the words I wanted to keep and pasting the names of stores in, I began the process of painting white out over the rest of the text. I scanned every page, and, luckily, by the time I’d finished that, Adobe Acrobat had advanced to the point that you could actually edit words inside a PDF. So I spent a lot of time taking this raw material and turning it into a cohesive book, moving pages and deleting more text. I think it’s a fun book and at the same time it points to the problematic relationship between the United States’ version of Christianity and the capitalist system.

The book was a semi-finalist for the Sawtooth Poetry Prize run by (the now sadly non-existent) Ahsahta Press in 2017. It’s been a little bit of a challenge to find the right publisher for GIITM, because every page needs to be printed in color and I’m not Mary Ruefle and the book is sort of specific and weird. You can read a good chunk of it in vol. 30 of Word for/Word. Shout out to editor Jonathan Minton for consistently being open to publishing the stranger forms my work takes; he also published an early version of the title sequence of Ablation in vol. 35 and is about to publish some pieces from what I hope will be my 3rd book, The Book of Matthew, in vol. 41. Matthew is actually the reason I haven’t been actively looking for publishers for GIITM recently. I wrote Matthew alongside Ablation, and they’re linked, in my mind. Like, Matthew is the aftermath, the shadow cast by Ablation. So I need those two books to come out back to back. I’ll start looking for publishers for GIITM again after I find one for Matthew.

RC: Is there anything else you’re working on you want to mention?

DSL: The Book of Matthew is finished, and I’m sending it out to publishers right now. It’s a book of miracles constructed from 3 types of materials: erasures of each miracle found in The Gospel of Matthew cut from various editions of The New Testament, ecstatic poems (some based on dreams, some based on dreaming), and epistles written to a Matthew, a messenger, an angel of my own making. By the end of the book, these materials elide and coalesce. It’s a book of dissociation, science, spell-casting, prophetic vision, intimacy, and other sorts of magic. As hinted at above, while Ablation addresses the sudden loss of my mom and my childhood trauma directly, while Matthew addresses the aftermath: my patterns, my (un)consciousness, my longing. The book also reckons with acculturated ideas of femininity and power and contains a lot of references to Radiohead. I sort of had to write the Matthew poems alongside Ablation because Ablation was painful to write. Most of the poems in Matthew felt magical and fun to write. I’m really excited for a couple of those Matthew poems to come out from Carrion Bloom Books as a pair of microchapbooks soon: Familiar Birds: House of Mesh (I) and Familiar Birds: House of Suet (II). So watch for those.

In addition to the microchapbooks and the cut up miracles coming out in Word for/Word vol. 41, poems from Matthew will be out soon in FIVES (that one’s a video poem actually), SOLID STATE, and mercury firs.

Right now I’m working on two things (have you noticed I like to write two things at once?). One is the sequel to Pilot, which I’m currently calling FARADAY; Pilot only uses scripts from the first 2 seasons of Lost, so FARADAY will cover the remaining 4 seasons. The other project I’m currently working on is called Wheel of Fortune; it’s a long long book-length poem about endlessness and circles that I’m writing onto a rolodex I bought at an open-air flea market in May of 2021.

Preorder your copy of Ablation now, out from 11:11 Press on November 1st.