I wouldn’t even bother writing about Coldplay’s latest record, but as the water of the music industry recedes, Viva la Vida has landed as a big fish in a little pond. Dave Allen exerted quite a bit of effort vilifying the record over at Pampelmoose, and while I don’t disagree with all of his points, I think his keyboard’s venom is at least partially misplaced. This is not a record review. Continue reading “Music for Magazines: This is Not a Record Review”

The Irony of the Archive

My parents have been living in their current house for over twenty years. My Moms’ part is a stockpile of paints, fabrics, and other craft supplies. Dad tends to save anything that he thinks might be useful later. Their combined efforts have amassed an archive that escapes any scheme of organization. I’ve overheard both mention recently that they had to go buy something that they knew they already had because they couldn’t find it among the clutter. Continue reading “The Irony of the Archive”

My parents have been living in their current house for over twenty years. My Moms’ part is a stockpile of paints, fabrics, and other craft supplies. Dad tends to save anything that he thinks might be useful later. Their combined efforts have amassed an archive that escapes any scheme of organization. I’ve overheard both mention recently that they had to go buy something that they knew they already had because they couldn’t find it among the clutter. Continue reading “The Irony of the Archive”

Recurring Themes, Part Seven: Categorical Contempt for Others

During a stint at a record store a couple of years ago, I had a lady come in looking for the new Neil Diamond record. As I located the CD for her, she started talking down to me, as if I had no knowledge of Neil Diamond’s history. Sure, part of this was because she thought I was younger than I was (no one expects a mid-thirties sales clerk with a master’s degree in a South Alabama record store), but part of it was indicative of a widespread elitism, a largely misplaced but ubiquitous contempt for others. Continue reading “Recurring Themes, Part Seven: Categorical Contempt for Others”

Building a Name: 21st Century Cave Painting

When pressed about his motivation for painting in the documentary Style Wars (1982), graffiti artist Duster explained that the elder writers give you a name and tell you to see how big you can get it. After watching this movie again recently it struck me that branding and advertising are charged with similar motivation and similar challenges. Continue reading “Building a Name: 21st Century Cave Painting”

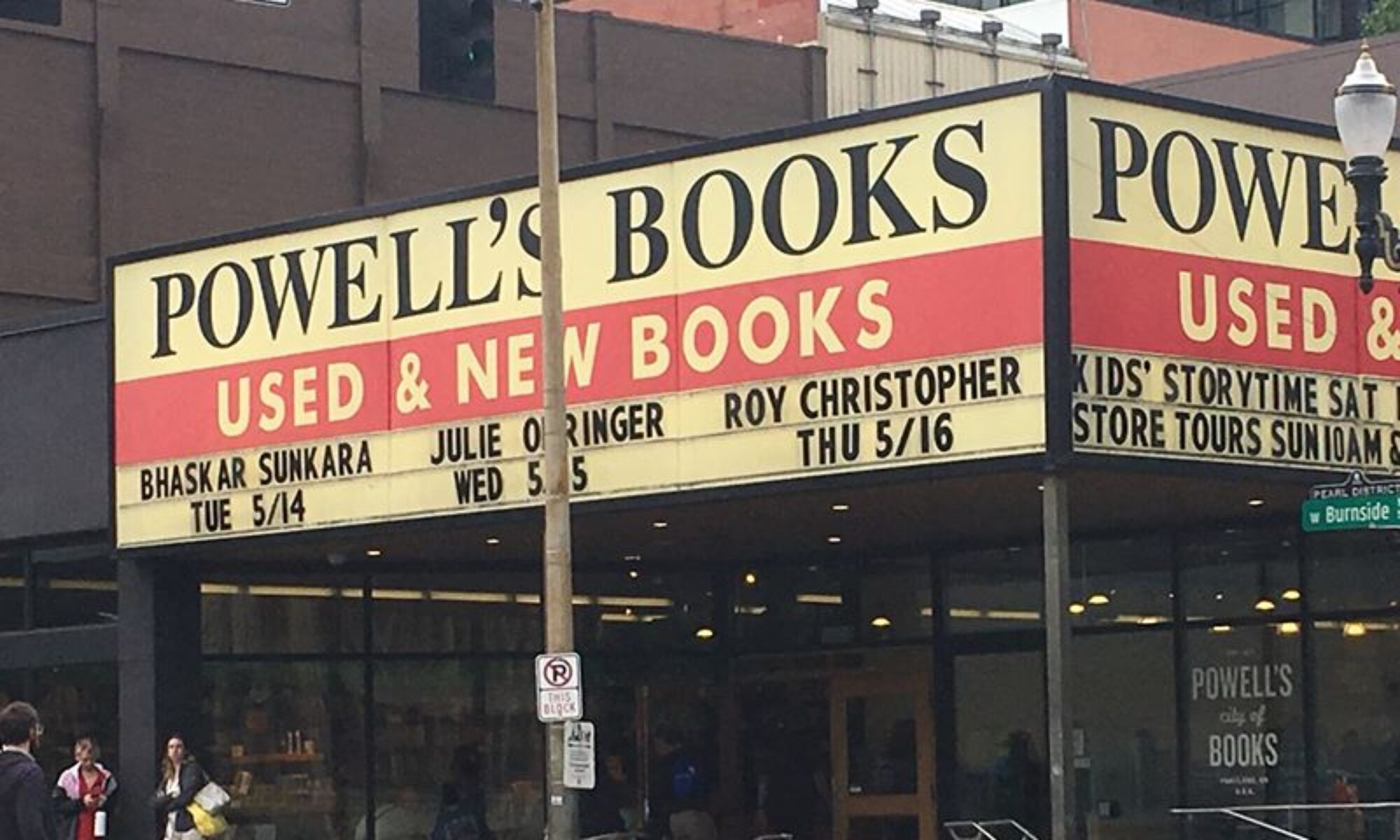

Shelflife: The Future of Books

The other day, Soft Skull‘s Richard Nash posted a link to a speech by Mike Shatzkin on the future of books and booksellers, calling it “dead-on.” Having heard the doors to traditional book publishing creek as they close, I have to agree with Richard: insights abound. It looks like the Cluetrain has finally reached the dead media…

One of Shatzkin’s main insights concerns the impact of the web on publishing. No, it’s not the old, knee-jerk “end of print” claim, but one that may still point to print’s end. Where the book industry’s organization is arranged around formats (i.e., it is horizontal), the organization of the web lends itself to topics of interest regardless of format (i.e., it is vertical). The file is now the medium of distribution — not the book or the magazine or whatever: The barriers between media dissolve online. He explains it thusly,

…the Internet naturally tends to vertical organization, subject-specific organization. It naturally facilitates clustering around subjects. And as communities and information sources form around specific interests, they undercut the value of what is more general and superficial information within horizontal media. At the same time, format-specialization makes less and less sense. Twentieth century broadcasting, newspapers, and books had special requirements that demanded scale, sometimes related to production but more often driven by the requirements of distribution. On the Internet, distribution is by files, and files can contain material to be read on screen or printed and read; it can contain words or pictures; it can contain audio or video or animation or pieces of art. When the file becomes the medium of exchange, not a book or a newspaper or a magazine or a broadcast delivered over a network with very limited capacity, it eliminates the barriers that kept old media locked in their formats.

The audio files of the music industry are much more suited for the digital revolution of production. That is, the shift from atoms to bits (though there is The Institute for the Future of the Book which hosts projects such as McKenzie Wark‘s G4M3R 7H30RY, Lawrence Lessig’s release of The Future of Ideas free online, and No Starch Press recently offered free torrents of a couple of their titles). Shatzkin argues that audio books, portable readers, and digital print-on-demand will enable the same for books. Even so, we aren’t seeing the total paradigm upheaval in book publishing that we’ve seen in music. Its transformation is happening piecemeal. For the book market, the shift is good for consumers and long-tail-ready retailers, but not so much for old-order publishers.

The audio files of the music industry are much more suited for the digital revolution of production. That is, the shift from atoms to bits (though there is The Institute for the Future of the Book which hosts projects such as McKenzie Wark‘s G4M3R 7H30RY, Lawrence Lessig’s release of The Future of Ideas free online, and No Starch Press recently offered free torrents of a couple of their titles). Shatzkin argues that audio books, portable readers, and digital print-on-demand will enable the same for books. Even so, we aren’t seeing the total paradigm upheaval in book publishing that we’ve seen in music. Its transformation is happening piecemeal. For the book market, the shift is good for consumers and long-tail-ready retailers, but not so much for old-order publishers.

For the smaller publishers, branding is now social. Building community through social sites — as Disinformation and Soft Skull have done — is essential, but it just doesn’t make sense for large legacy publishers like Harper Collins or Random House. These smaller web-age publishers are much more agile and attuned to the times. And, as some older publishers are finding out, having an extensive back catalog does not necessarily mean having viable long-tail content.

For the smaller publishers, branding is now social. Building community through social sites — as Disinformation and Soft Skull have done — is essential, but it just doesn’t make sense for large legacy publishers like Harper Collins or Random House. These smaller web-age publishers are much more agile and attuned to the times. And, as some older publishers are finding out, having an extensive back catalog does not necessarily mean having viable long-tail content.

Competition is stiff and getting stiffer, the zeitgeist is leaving books behind, and the shift to digital is still infecting everything. What does all of this mean for book publishers and authors? As a self-publisher and as a writer, I’ve seen the effects of these trends at work firsthand. Though I opted for a more traditional route with Follow for Now (I’m maintaining an inventory of atoms), print-on-demand services are good and getting better. The digital options are now rivaling the traditional paths to print. This is good news for writers looking for ways to get their ideas out there. The same can be said for the ease of blogging. Making the transition to “paid writer” or “author with a book deal” is the difficult part, though it’s still possible: Christian Lander, the guy who started the “Stuff White People Like” blog, recently landed a reported $300,000 book deal with Random House.

But where is the middle ground? Lander’s deal is clearly an exception to the new rules, and to call the unpaid blogging community “overcrowded” is to do the word a disservice. Can writers — like their musician counterparts — make a living in the new market? Is its resistance to digital assimilation a boon or a burden for book publishing?

The Contextual Modality of Culture

I used to work as a juvenile rehab counselor at a maximum security facility in Washington state. There were third-generation gang members locked up there, caught in the crossfire where the rules and mores they’d grown up with clashed with those of the larger society. Continue reading “The Contextual Modality of Culture”

Mind Wide Shut: Recent Books on Mind and Metaphor

Scientists have used metaphors to conceptualize and understand phenomena since early Greek philosophy. Aristotle used many anthropomorphic ideas to describe natural occurrences, but the technology of the time, needing constant human intervention, offered little in the way of metaphors for the mind. Since then, theorists have compared the human mind to the clock, the steam engine, the radio, the radar, and the computer, all of increasing complexity. Continue reading “Mind Wide Shut: Recent Books on Mind and Metaphor”

Camera Obscura: Cloverfield and the Myth of Transparency

The scariest moment of Bowling for Columbine (2002) was watching the security camera footage of the shootings. Something about seeing that black and white representation of Eric Harris’ and Dylan Klebold’s grainy forms stalking the cafeteria that morning was just plain eerie. Continue reading “Camera Obscura: Cloverfield and the Myth of Transparency”

Building a Mystery: Taxonomies for Creativity

In a 2005 Daniel Robert Epstein interview, Pi director Darren Aronofsky likened writing to making a tapestry: “I’ll take different threads from different ideas and weave a carpet of cool ideas together.” In the same interview, he described the way those ideas hang together in his films, saying, “every story has its own film grammar so you have to sort of figure out what the story is about and then figure out what each scene is about and then that tells you where to put the camera.” Continue reading “Building a Mystery: Taxonomies for Creativity”

An Inconvenient Youth, Part Two

![]() Remember when music was good — when bands stood for something and the music they created was from the heart? Remember when music was real?

Remember when music was good — when bands stood for something and the music they created was from the heart? Remember when music was real?

I remember a college professor trying to tell me that Nine Inch Nails’ Pretty Hate Machine was “fake, plastic music” while Jimi Hendricks’ Are You Experienced? was “real.” I recently heard the same argument about the fakeness of My Chemical Romance, with NIN as the “real” example.

Since writing last entry, I attended a skateboarding session where there were several skaters much older than I am. One said skater couldn’t seem to get his head in the present. All he talked about was “how things used to be” — the tricks, the ramps, the attitude, the music — everything. Needless to say, this grew tiresome very quickly, and I was glad when the younger crew finally showed up to session.

Some cultural artifacts get “grandfathered” in before our critical filters develop — shows that you remember loving that would probably annoy you now. Others however are chosen by your newly discerning pre-teen mind. Be it Bad Brains, The Wipers, The Sex Pistols, Dead Kennedys, Fugazi, Nirvana, Nine Inch Nails, or My Chemical Romance, everyone has that “punk rock moment” where he or she realizes that the shit on the radio or the shit that their dad likes is wack. This does not make the stuff that you used to like better than the stuff your daughter likes. This does not make Nine Inch Nails “better” than My Chemical Romance (there are plenty of other reasons for that).

As Doug Stanhope would put it, Nine Inch Nails is good to you because being young is good. Everything was better then, but not because it was 1991 (or 1968), for example. It’s because you were young then. The same can be said for the Jimi Hendricks example and my college professor above. Sorry, everyone, “Three’s Company” was not necessarily better than “The King of Queens.”

Part of this is cognitive. Our brains’ ability to create and store new memories simply slows down — to a near-stop, therefore making our most cherished memories those of a bygone era, those of our youth. And when we remember those times, we reify them, making them stronger (Freud called the process “Nachtraglichkeit” meaning “retroactivity”).

So, the aging skateboarder lamenting the olden days when skateboarding was more about gnar than fashion (Ed. note: it’s always been about both) might be suffering from cognitive deceleration, but most likely he’s just being nostalgic boor. Farbeit from me to quote Bob Dylan, but he once said, “nostalgia is death.”

My college professor (who’d probably be proud of me for quoting Dylan, even if I’m using it against him) was just being nostalgic as well. Nostalgia is not inherently bad, but when it comes from a sad place (as in our lamenting skateboarder above), then it indicates a dissatisfaction with the present. This, I believe, is when it becomes death.

We should all always be working toward making these the good ol’ days. The day I’m looking back, lamenting the now, is the day I want to cease.

Sources:

Johnson, S. Mind Wide Open. Schribner: New York, 2004.

Watson, J. D. Avoid Boring People. Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 2007.

Watson, J. D. “On Enduring Memories” SEED Magazine, April/May, 2006. p. 45.

Thanks to Reggie for sending me the Ruben Bolling comic.