My friend Dave Allen passed away the other day. Like most people who knew him, Dave was not only a friend but also a mentor to me. Through his music and his thinking, it’s difficult to take measure of the influence he’s had on us. I last saw Dave in 2022 when I spent a week at his and Paddy’s house in Portland, collaborating with them on a book idea.

In tribute, I’m sharing a piece I wrote about Dave and Gang of Four a few years ago and an interview I did with him in 2008. There’s really no way to do his influence justice, but this is all I have.

Rest in peace, Dave. You’re already sorely missed.

Return the Gift: Gang of Four

To create a spike of novelty high enough to be seen by history depends on a lot of things aligning: an open-armed zeitgeist, an interested public, a little bit of chaos, and a lot of charisma. Sometimes they become folklore, affecting only those who were there, like Woodstock, Altamont, or the June 4, 1976 Sex Pistols show in Manchester: Supposedly everyone there left that show dead-set on starting a band. There’s even a book about it. Other times these events are recorded, as great performances, works of art, books, or records.

Once the smoke cleared after the detonation of punk, there was still so much work to be done. Gang of Four’s original line-up tapped into a tectonic shift in the times. As Mark Fisher writes in The Ghosts of My Life, “It has become increasingly clear that 1979-80… was a threshold moment—the time when a whole world (social democratic, Fordist, industrial) became obsolete, and the contours of a new world (neoliberal, consumerist, informatic) began to show themselves.” It was also the dawn of post-punk. In tangents like tentacles, Joy Division, Wire, The Fall, PiL, Talking Heads, Television, and Gang of Four, among others, were stretching punk in ever new directions.

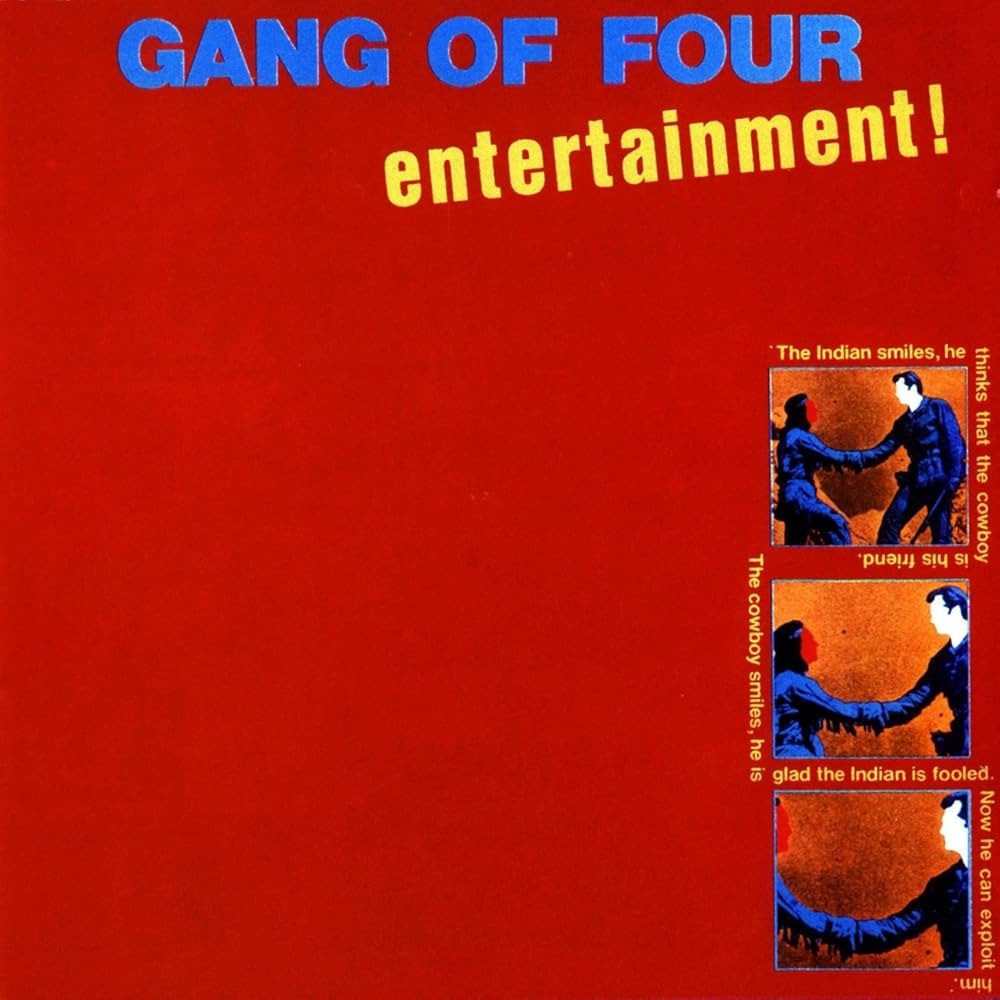

One of the more significant of these, Gang of Four combined the lean muscle of punk with the bare bones of funk. Lyrically social and political, their lanky limbs swung hard and wide against the “middle-class malaise” of the 1970s. The first time I heard Gang of Four’s Entertainment!, suddenly much of what I was already listening to made much more sense. Fugazi had a lineage. Naked Raygun had context. Wire had contemporaries. During the post-Lollapalooza package tour phase, I finally saw them live in 1991. It was a woefully crippled line-up that only included Andy Gill from the original Four, sharing the stage at Atlanta’s Fox Theatre with a motley mess of bands: Young Black Teenagers, Warrior Soul, Public Enemy, and The Sisters of Mercy. The fact that Gang of Four was considered viable in that line-up ten years past their prime is significant though.

Woven as an influence and wielded as an instrument, Entertainment! remains a relevant strand of modern music. Frank Ocean sampled “Anthrax” for the song “Futura Free” on his 2016 record, Blond, and El-P sampled “Ether” for “The Ground Below” from Run the Jewels’ 2020 record, RTJ4. It was #81 on Rolling Stone magazine’s 2013 “100 Best Debut Albums of All Time” list, and in 2012, when they updated their 2003 list of the “500 Greatest Albums of All Time,” Entertainment! moved up from 490 to 483, a seven-spot jump in a decade, over 40 years after the record was released. It stands at number 8 on Pitchfork’s “Top 100 Albums of the 1970s” list for 2004.

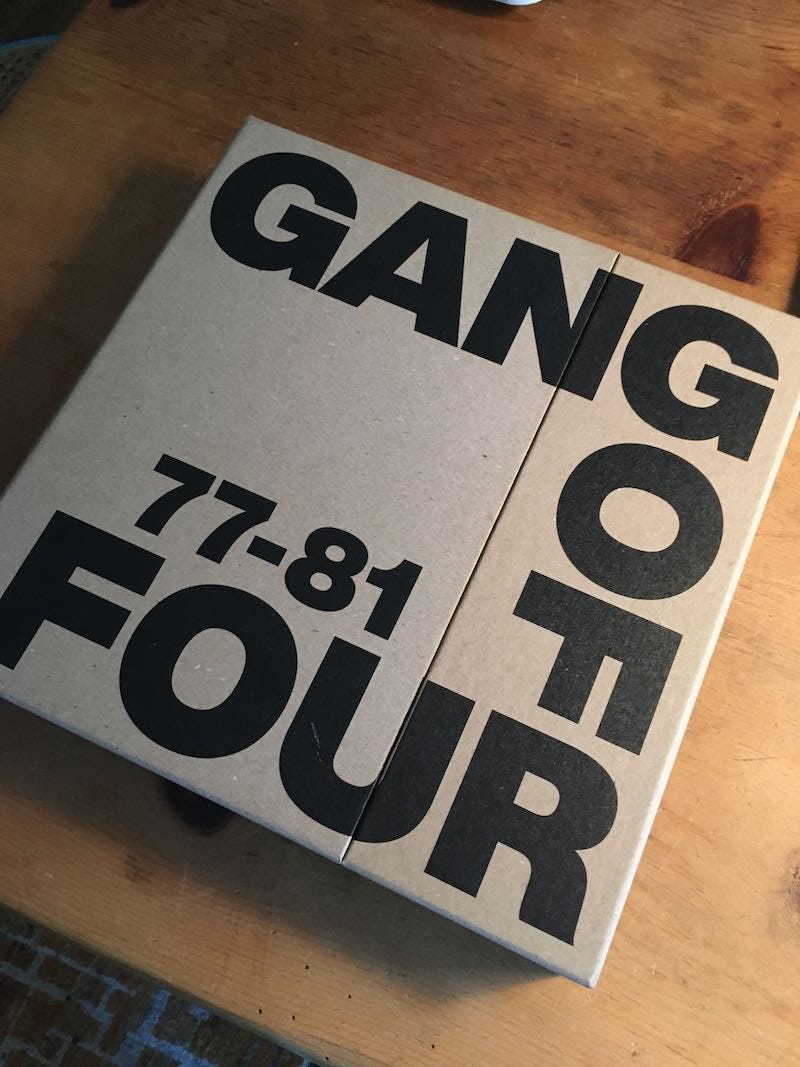

So, when the original four reformed in 2004, as if to prove how strident those early records were, they rerecorded those classic songs. The result was Return the Gift, which features predominantly tracks from Entertainment! And its follow-up, Solid Gold, performed live on a soundstage. Even 2021’s retrospective boxset represents their earliest era: Gang of Four 77-81.

By the time they released Return the Gift in 2005, there were bands that had drawn direct influences from the original Gang of Four. People were comparing Franz Ferdinand and Bloc Party to them. “Those bands helped us get back into the limelight with a whole new generation of music fans,” says Dave Allen, “who came along thinking they were going hear Bloc Party or Franz Ferdinand and then got their minds shattered.” Though they are often considered overtly political, Dave bristles at the connotation. “People would say, ‘Rage Against the Machine is just like Gang of Four.’ As much as I respect those guys and what they do, our aims were very different. We weren’t revolutionaries. We were dissecting everyday life.”

After touring with the original line-up, Jon King and Andy Gill had set their sights on a new record, but Hugo Burnham and Dave didn’t think the world needed a new Gang of Four album. Dave, having spent many intervening years consulting bands on negotiating the music industry’s new digital landscape, wanted to do something new, something different. He told me at the time, “If we don’t own the idea, there’s no point in doing it.” He continues,

What I’d wanted to do instead was set up cameras in our rehearsal room in London and do what Radiohead did. This would have been a perfect Gang of Four moment: You can check in on our working methods, you can check in on the arguments that take place. You’d get the chemistry of the band, and then I just felt like, let the crowd decide: What do you think is worth following up on? We’d still never make an album, just complete these songs and leave them up on YouTube so millions of people could stream them forever, and you don’t have to pay a thing. Meanwhile, our cachet goes up in the world for touring, and we can go out again. That’s what the Web’s for. In music, I think the Web gives you this massive distribution system out of the hands of radio, out of the hands of distributors, out of the hands of record labels. What could be better for rock ‘n’ roll than that?

This sense of independence, the lingering influence of punk, runs through Dave’s many endeavors. The novelist Rick Moody writes of him,

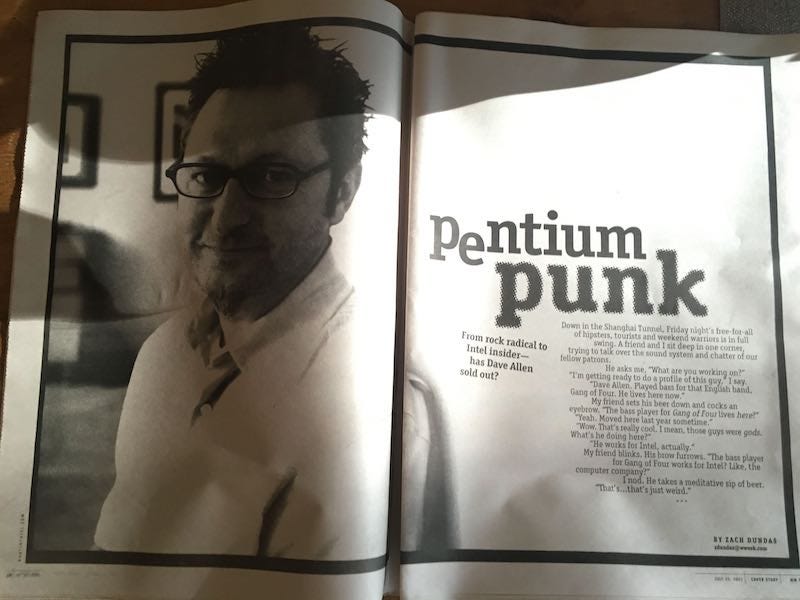

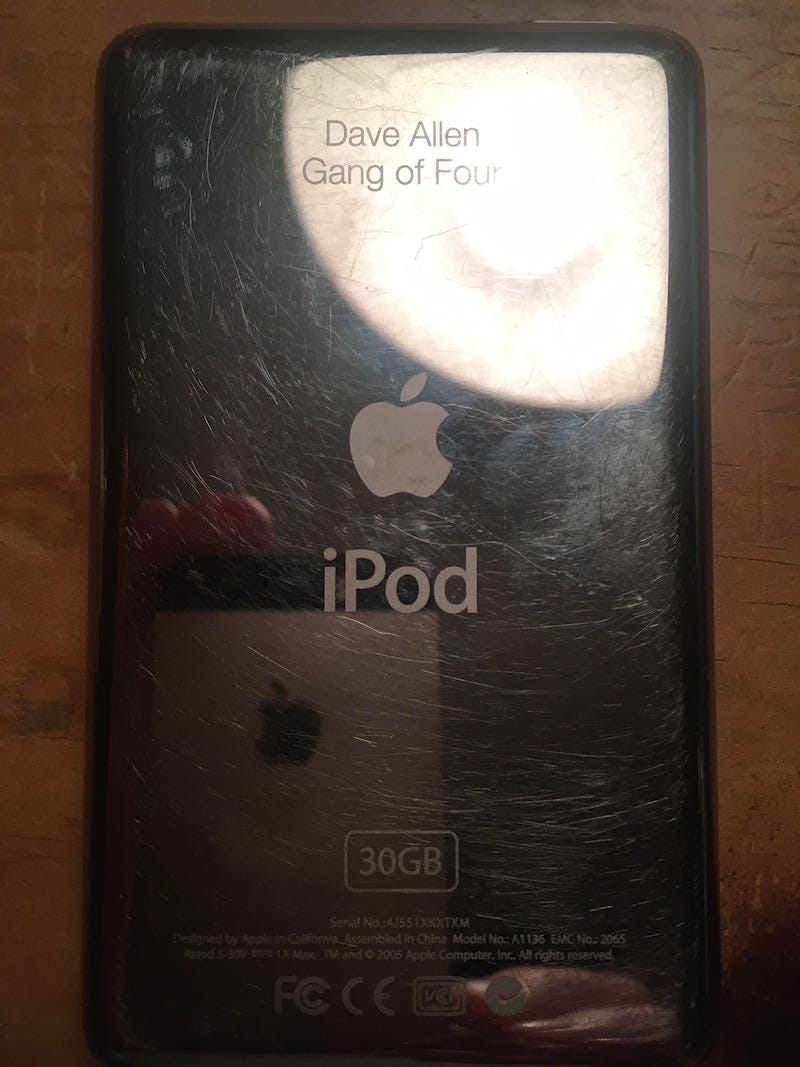

In calling Dave Allen an Internet strategist, or a pundit of the digital realm, or a high-tech agit-prop genius, you would be leaving out the job he had before that, when he was Dave Allen the bass player, first in Gang of Four (on their first two albums, and then for a couple of years during their reunion victory lap), and later in Shriekback. As such, he has experienced all of the vagaries of the music business as a player, producer, label owner, and now as a copyright owner of a great number of great songs from the seventies and eighties that are routinely streamed online. Few people of my acquaintance are better situated to talk about distribution and the difficulties thereof without romanticizing the story.

If you know Dave Allen, you probably know him from his time in Gang of Four, but from post-punk and the music business to the post-internet, Dave has been ahead of every curve. A life and lessons from over four decades traversing the interstices of not just music and technology but also art and culture, Dave Allen is one of our most outspoken innovators and advocates.

Every Force Evolves a Form

An Interview with Dave Allen, 2008

I can’t remember the first time I heard Gang of Four, but I do distinctly remember a lot of things making sense once I did. Their jagged and angular bursts of guitar, funky rhythms, deadpan vocals, and overtly personal-as-political lyrics predated so many other bands I’d been listening to. Dave Allen was the man behind the bass, and now he’s the man behind Pampelmoose, a Portland-based music and media blog.

I sat down with Dave in May 2008 for a lengthy beer-soaked session over Mexican food, and I managed to glean the following dialogue from it. We talked about Gang of Four, Dave’s personal history from forming that band to running Pampelmoose, the questionable state of the music industry, and why Portland is the place to be.

An update was planned, but now that Dave has parted ways with Gang of Four (along with drummer Hugo Burnham) again, I figured I’d go ahead and run this interview as-is. Dave’s ideas about the state of the record industry (about which he’s written extensively on Pampelmoose) and how Gang of Four should release their music clash with the band’s more traditional leanings. The seeds of his departure can be seen germinating in the talk below.

Roy Christopher: Seeing all of the sound-alike bands around, you guys originally got back together and did your old material.

Dave Allen: Yeah, the point that that was really validated was when we played in the West of England at the All Tomorrow’s Parties “Nightmare Before Christmas” show, curated by Thurston Moore, and we were the co-headliners. We’d already played with them the previous summer at the Prima Vera festival in Barcelona. We actually followed them that night, and I was really concerned, but what I realized was, although that band puts out new albums every now and again — Nurse, Rather Ripped… They make great records. They never stopped. Now, you might argue that nothing changes with Sonic Youth, so their style is the same: You just get a new batch of songs from Sonic Youth. And there’s something remarkably comforting about that, but at the same time, the moment when they launch into something from Daydream Nation, and they expand on it because they’re a jam-band at times, but the most interesting jam-band ever to be seen live. They are such a superb band. Forget everyone else. But it dawned on me, we and they are legacy bands. People don’t necessarily come to hear the new material. So, you better be sure to pack your set with a lot of old material. They’ve got twenty albums to draw on, right? We’ve only got two. Really. It limits the amount of time we can be on stage, but at the same time, we’re not ones to overstay our welcome. Live, those songs are more intense than ever before. They have a new vibe that I really like.

Anyway, point being, once you realize that people are coming to see you to hear the old songs — including the new crowd that turns up, by the way — then you’re okay.

If we do record twelve new songs, six of which are really good, then how do we put that out? My argument would be that we’re Gang of Four, and we’re supposed to do things a bit differently. So, do we do it through a cell-phone provider? Something different. Or should we give it away digitally and just press some heavy-gram vinyl to sell at shows? The days of doing a CD are over. That’s my argument. Now, I don’t know if Jon and Andy would agree, but the point being that the material can be used in many different ways. One idea that we’ve been kicking around with this new song that I really like. Jon’s got this thing about caffeine culture and it’s a really cool direction we’re going in, and it’s good, old-fashioned Gang of Four. I’m really enjoying it. Now, what if we perversely actually went to Red Bull or whoever and see if they want to release it? It’s not available anywhere else except in their ad. Then make it viral online where you can download the Red Bull/Gang of Four video, and so on. That way it gets spread around the globe in different ways. And the point being not to sell anything, but Red Bull would pay us for the campaign, and we get back on the road, which is where we do best. We play live, we get paid well, we can sell t-shirts and vinyl, so the concept of signing to a label, putting something out, and touring on it is so ridiculous to me. If we don’t own the idea, there’s no point in doing it.

RC: Right, it’s just like the legacy idea. You used the Rolling Stones as an example. The new records are just an excuse to get out on the road and play the old songs live.

DA: That’s all it is.

RC: Do they really realize that? You say they do, but I think it’s that you realize that. I don’t think the Rolling Stones think of themselves as a legacy band. I think they’re still trying to make another “great” Rolling Stones record.

DA: I think you’re right. That’s the counterpoint, right? They may not have realized it and I think all bands want to keep creating, and what I’m saying is—

RC: “We’ve done our good stuff. Let’s just keep doing it.”

DA: Right. There are other ways to be creative, so I would argue that doing my label, trying to find new bands is creative, and now I’ve got my heavily trafficked blog.

RC: Right. You have an outlet, and you get to play live.

DA: Yeah, why would we kill ourselves to do a new record when no one wants to buy it anyway?

RC: There’s no good way to say it.

DA: It’s all downhill. It’s retreat.

RC: Yeah, when you first mentioned the legacy band idea, it really resonated with me, but I finally got around to watching the Metallica documentary, and wow. Those guys are just so obviously past their prime and just killing themselves trying to make a new record. It just ends up being a parody of what they once were, and I think that really speaks to your idea of being a legacy band –- and realizing it.

DA: I would argue that who’s to blame here are the labels. The labels are to blame. It’s like when Coldplay decided not to make an album because Apple was about to be born, and Chris couldn’t write songs or whatever, EMI’s shares dropped 15%, because it was all about the biggest band on the label. Well, Metallica are huge, so it’s the same thing. All the heads of Warner Brothers will be pushing them, “Look at the share price! We need an album from you guys!”

RC: It was totally like that in the film! When James left for rehab, the label freaked, like “Oh my god, our cash cow is falling apart!”

DA: Well, didn’t Geffen pretty much go away after Kurt killed himself? Nirvana was Geffen’s cash cow.

RC: Not like they lost any when he died… In 1995, Sub-Pop’s second biggest seller was Sebadoh’s Bakesale. Their first? Nirvana’s Bleach! In 1995, Sub-Pop could’ve not released anything, just kept Bleach on the market, and made money.

DA: So, my point about these legacy bands making records is, the Rolling Stones will be given a million dollars every time they want to make a record. The label can recoup that money. They’re not going to get rich off of the record, but it revitalizes the back catalog, and puts the band on the road. Otherwise, why would they bother to get out of bed to record? They’re past their prime as songwriters. I’m sorry, there’s not anything redeeming about it.

I think it’s interesting that Sting got The Police back together but didn’t bother to make a record with those guys. And Sting is the consummate songwriter. Meanwhile, the cheapest ticket on the Police tour is a hundred dollars.

RC: You know how much the good ones are? Nine-hundred…

DA: Are they?! Let’s go back to that one-hundred dollars: There goes the music industry! The live side of it is growing, but there goes the recording industry. The back catalog is the only money to be made.

RC: What about Mötley Crüe? They had to prop Mick Marrs up, and Vince Neil is huffing and puffing and barely making it through one of those tours. They made millions of dollars and didn’t even do a new record!

DA: You don’t need to.

RC: Kiss did what, three reunion tours? And all three of those years, those were the biggest tours of the year.

DA: People don’t want to hear the new material.

RC: They want to hear “Rock and Roll All Nite.”

DA: It’s a reminder of your youth.

RC: It’s nostalgia marketing.

DA: Absolutely.

RC: It’s one of the strongest things out there.

DA: It’s what we did on our holidays, twenty years ago.

RC: Right.

RC: So, why Portland?

DA: In late 1999, I was living in Lookout Mountain with my kids, all computer kids, and I went to a friend of mine Nigel Phelps who’s one of the top art directors in the movies, he did Titanic and all sorts of big movies, English guy, — his eldest daughter, I saw that she was on the computer, on AOL, and she was talking to herself saying, “You’re on dial-up, you’re not on broadband,” and I asked her if she was arguing with someone about who was on dial-up and who was on broadband. She said, “No.” On Napster, when you selected a song it tells you the bandwidth availability. So, when it was really slow, she would IM the person and say, “You liar. You’re on a 28K dial-up. You’re not on broadband.” That was my first exposure to Napster, and I was like “What the heck is this?” I look and she’s got all of this free music. Now, I was at eMusic, where we charged 99 cents per song, and the next morning, I went into the office and emailed the head guys and said, “Guys, you’re done. Everybody is getting free music from Napster.” Their attitude was that it was illegal and that they’d soon be put out of business. And I was saying, “Not before we go out of business.” And that’s exactly what happened.

Then around 2000, when the market sank and the whole dotcom thing fell in the toilet, I got the call that they were closing the LA office. I got a call from a headhunter that some guys in Portland wanted to fly me up and talk to me and would like to hire me for a similar position. I liked Portland, I’d been here a lot, I had friends here already, but I wasn’t ready to leave the big city just yet. Anyway, it turned out to be Intel, and on the campus here right outside Portland, they had this thing called New Business Investments, or NBI, and I was asked to join the Consumer Digital Audio Services or something like that. It sounded interesting, so I joined up. They were looking at internet connected devices, an MP3 player—pre-iPod—and different ways to get your music, Home Entertainment servers, and the thing we were building that you see now was this bridging system that transmitted music files from your computer to your legacy Hi-Fi. 802.11b had just arrived, so we were working to get the music from there to there, wirelessly. My job was to go to Yahoo music and these other content providers and license them for our service. It was a great idea. The problem was, Intel is known for developing amazing stuff and then getting cold feet at the last minute and not bringing it to market. At home I’ve got five MP3 players that are better than the iPod. There’s a soundcard in them, engineered to perfection. They’re amazing. The only problem was it’s just a flash device, it only had a 128Kb flash card for memory, and no one had thought of a adding slot where you could upgrade the memory. Never came to market. That was that.

They’d paid for me and my family to move up, I’d bought a great house, and I think it’s a great city. I don’t feel the urge to move back. I’m a booster for this town. I love it.

RC: I’ve only been here for two months, but every other day there’s someone else here that I didn’t know was here, or some event that I didn’t realize happened here. I never thought about moving here because Seattle has been my adopted home for so many years, so I never thought about dropping down here, but since I did… It’s an amazing town.

DA: Anthony Keidis just moved here.

RC: Really?

DA: Ironic, huh? Now I can ask him about my royalties. [Laughter] “You can come to my barbecue. Please bring blank check.” [Laughter] Everyone’s here. The Shins, Johnny Marr…

RC: His being in Modest Mouse…

DA: You can say it, Roy.

RC: Okay, I hate Modest Mouse. [Laughter] I love Johnny Marr, but I hate Modest Mouse. It’s funny that the Mouse House is right over there.

DA: Yeah, I ran into Isaac Brock’s girlfriend, and he came by the office to get some stuff, and he said I should come over, that there’s someone there I’d probably like to meet. So, I went over there and I walk upstairs and there’s Johnny Marr. He sees me walk in and he’s like, “What the fucking hell are you doing in Portland?” And I said, “Well, what the fucking hell are you doing in Portland?” [Laughter]

They’re an interesting band to watch because they were a multi-platinum band, and now they’re not. You have to make money on the road.

RC: That’s another area that hip-hop is missing out on. Hip-hop is not known for big live shows – and it should be. The lyrical element of hip-hop is one of the most exciting things to see live, but the acts that excel at that part of it are not the acts that are selling the records and doing those tours.

DA: The underground aspect is interesting, like The Roots do well touring, Blackalicious… But the bigger it gets, the more it slows down. I mean, is T.I. going to do a big arena tour?

RC: No, but T.I. is one of the guys who’s still selling records.

DA: Yeah, he’s fine, but the minute it drops off, what can he fall back on?

RC: Right. Then he can go be Jay-Z.

DA: That may be one of the things that hurt live hip-hop: It was so easy to sell records, it was like why bother going on the road?

RC: Well, for a long time hip-hop had a hard time getting security for shows because it had been tainted with this “violence” tag.

DA: And it was never as bad really as your average big rock show. It’s just racism.

RC: Yeah, it’s a race thing and something the press loves to play up, and it’s completely untrue, but it keeps you from getting insurance for a hip-hop show. The reality is, the insurance company is like, “Ice Cube? Oh, hell no!”

DA: Right. Every black person is packing, and there are 50,000 of them in an arena, we’re not covering that. And then Guns N’ Roses comes to town and there are two stabbing deaths—

RC: And all of the seats in the arena are ripped out and thrown on stage.

DA: Yeah, but those are all white guys from the suburbs.

RC: So, what are your goals with Pampelmoose?

DA: It started it off like it did with my label World Domination, maybe a little too starry-eyed. I feel I’ve done really well in music, and I’m generally a very positive person.

RC: That’s one of the things I love about you, Dave.

DA: Aw, thanks [Laughs]. I look at bands and at the scene, and I feel like I’ve gotta give back. I volunteer a lot and I try and help, probably to my detriment, too much sometimes. So, I worry that I start off with great ambitions and sometimes let people down, because you get over-burdened and everybody wants a piece of it. You back up and think, “I can’t do everyone, so I shouldn’t do anyone.”

RC: It’s hard to find a balance there.

DA: It is. It’s so difficult, but I think we’ve found some kind of balance with Pampelmoose, and a group of friends and I were able to apply ourselves to a website that became a company that can help artists to sell some of their stuff, come on by anytime for free advice, bring their contracts -– I have a lawyer friend who charges very little to look over that stuff. Pampelmoose is also an extension of my social life. I’m very active socially. I can’t be at home. I’ve got to be out. I like being with people, and that’s no offense to my family. I like being with them, too. So, Pampelmoose has become an extension of my personality. I’ve tried things like this in the past with fanzines and writing, but it’s so difficult. You have to get them printed, get them out there.

RC: It wasn’t a fanzine, Dave. It was an art project. [Laughter]

DA: That’s true, and that’s my problem too, I get too deep into the project and it gets too ambitious and takes on a life of its own, then after the fall, I realize I over did it again. With Pampelmoose, the safety net was the blog. Because once the blog took off, and I believe it was January 2006 was the first post, and I have no idea where it’s going to go, but I did have the idea that I could open the doors to a community. That’s the thing I love about blogging, with the comments, people can call bullshit on me. The interesting thing for me was, six months go by, and no one’s calling bullshit, and then you get confident. And it wasn’t a lot at first, I think in the early days if we got a thousand visitors in a month, that was a lot, but it did pick up and start attracting visitors. Then I began to take it as seriously as everything else I was doing. I’m the editor. I’m the public voice. I’m the journalist. I’m the copy editor. I’m the layout guy. And at first, I thought I might be building something that I couldn’t maintain, so I hired a bit of a support team. Then I learned to fly. I learned some basic HTML code, I learned to crop photos… Every post has an image, any image. It doesn’t have to go with the rest of the story. So, it has a little art aspect to it, if you will. In the past eighteen months it’s morphed totally into this blog. Pampelmoose is the blog, and as a side note, we still sell CDs, T-shirts, and give advice to local bands. So, getting up every day and having an opinion and having people comment on it drives the whole thing, and now that the traffic is up, it’s like, “Oh, shit.”

RC: Yeah, but it validates everything you’re doing there.

DA: Right, but just having explained it, it’s still weird. It’s not like we’re Wal-Mart, and we do this.

RC: Right, but with Wal-Mart, there’s a precedent. “Remember K-Mart? Like that, but better.” When you’re doing something like this, it’s more ambiguous. People ask me what my book is about, and I say it’s a collection of interviews. “Well, what’s the theme?” You have to read it. So, it’s frustrating, but if you read it, you get it. Even if you only read one interview per section, a theme emerges. I think Pampelmoose is the same way. If you go there and dig around, read, and become a part of it, it fits, but there’s no one-line explanation for what’s going on there.

DA: It is intriguing. It’s not Pitchfork, where they get a million hits a month, and it’s like, “What’s the point?” At the same time, I can’t deny their success. They’ve done it well, but now you’ve got this unfettered fan-boy day out where you can kill something before it even has a chance.

- These are excerpts from two upcoming books that Dave had a hefty hand in. The first bit is from The Medium Picture, a book heavily influenced by Dave and his thinking. That one comes out October 15th from the University of Georgia Press. The second is an interview I managed to record in 2008, when we both worked at Nemo Design in Portland. That one is in my second interview anthology, Follow for Now, Vol. 2.

A professor in English with appointments in Film and Media Studies, Comparative Literature, and Global Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara,

A professor in English with appointments in Film and Media Studies, Comparative Literature, and Global Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara,

SW: There is no question that working a 12-step program of recovery saved my life. I’m a drunk junkie of the hopeless variety. There is no logical reason that you and I should be having this conversation. By all accounts, I should have died long ago. I tried to get sober a time or two by using self-will and I never got more than a handful of weeks under my belt. I just couldn’t do it, until I did the work outlined in the book. I’m not blessed with the capability to just turn off my need for oblivion. I was aware of this fact for a long time, I just thought it was my lot in life. When I started doing the program, I thought it was bullshit and wasn’t gonna work for me because, you know, I’m unique. But as I got into it, something happened. What that something is, I’m still not sure, nor do I care to know. I try not to think too deeply about the how’s or why’s. I just do what I’ve been taught and it keeps me clean, plain and simple.

SW: There is no question that working a 12-step program of recovery saved my life. I’m a drunk junkie of the hopeless variety. There is no logical reason that you and I should be having this conversation. By all accounts, I should have died long ago. I tried to get sober a time or two by using self-will and I never got more than a handful of weeks under my belt. I just couldn’t do it, until I did the work outlined in the book. I’m not blessed with the capability to just turn off my need for oblivion. I was aware of this fact for a long time, I just thought it was my lot in life. When I started doing the program, I thought it was bullshit and wasn’t gonna work for me because, you know, I’m unique. But as I got into it, something happened. What that something is, I’m still not sure, nor do I care to know. I try not to think too deeply about the how’s or why’s. I just do what I’ve been taught and it keeps me clean, plain and simple.