My favorite actors tend to play minor characters. There’s something truly special about the MVPs on the sidelines who score wins for the team without much notice. They get bonus points if they’re also writers behind the scenes. DC Pierson has haunted the edges of my psyche for years. He’s popped up on Community, 2 Broke Girls, Key and Peele, Weeds, and a few Verizon commercials, among other places. Somewhere along the way, I started following his social media antics, subscribed to his newsletter, and found his books. A creator in the true Renaissance style, Pierson can do anything — and make it funny.

I first saw Pierson in 2009’s Mystery Team, a collaboration between him Dominic Dierkes, Dan Eckman, Donald Glover, and the inimitable Meggie McFadden, that also features Aubrey Plaza, Ellie Kemper, Bobby Moynihan, John Daly, Neil Casey, Kay Cannon, and Matt Walsh, among others. It’s a juvenile adventure that feels like hanging out with your friends, causing mischief during a summer in middle school.

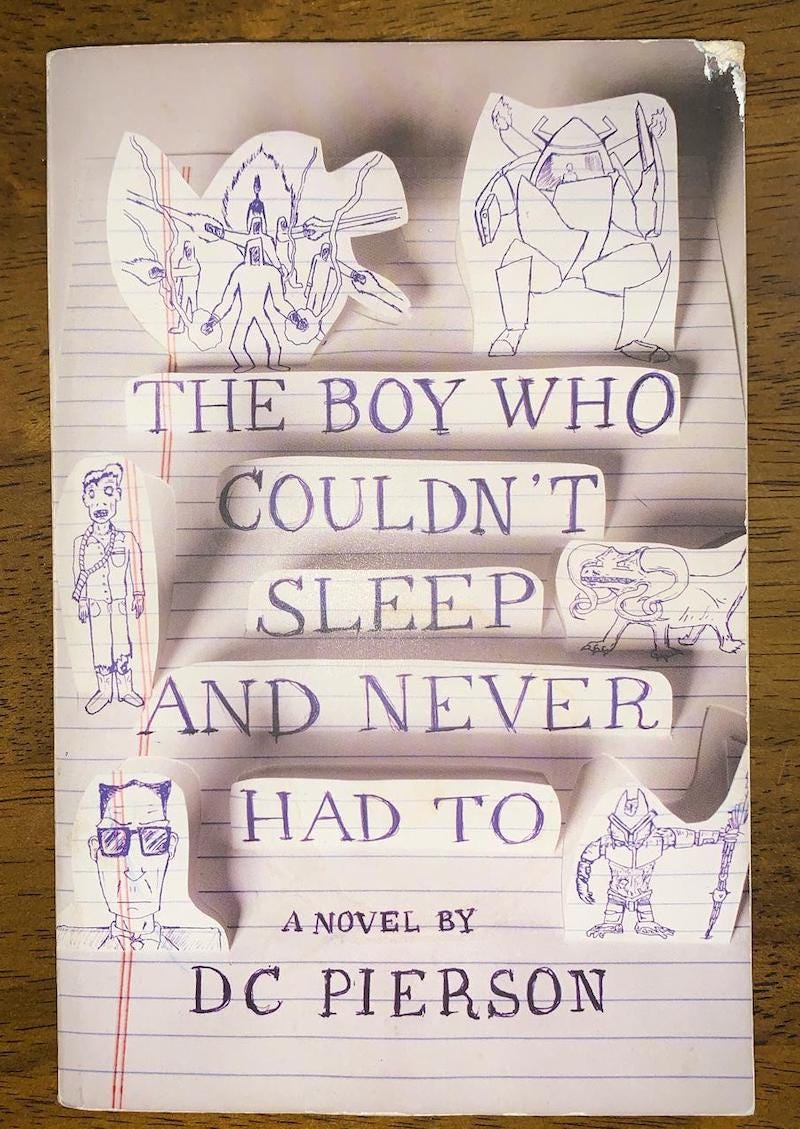

Pierson has also written for the VMAs and MTV Movie Awards. A veteran of improv comedy, his latest creations, “The Architect Who Built New York” video series and an adaptation of his first novel, The Boy Who Couldn’t Sleep and Never Had To (Vintage, 2010), are no less silly than his first— and no less serious.

Roy Christopher: I first saw you in Mystery Team (2009), which you co-wrote. In the meantime, the cast and crew of that movie has become a who’s who of modern comedy. How did that project come about?

DC Pierson: That project was the (probably? We’ll see) culminating effort of DERRICK comedy, a sketch group I was in with Donald Glover, Dominic Dierkes, Dan Eckman, and Meggie McFadden. We’d made a lot of videos that got popular at the dawn of the YouTube era and pooled any money we made from touring, merchandising, and the barest beginnings of monetization, and along with some money from friends and family were able to shoot a feature. Prior to that we’d written a feature we wanted to try and get made the traditional way, and when it became clear that wasn’t gonna happen we wrote something we could conceivably make on an indie budget, including using Meggie’s parents’ house or Dan’s uncles’ hardware store / warehouse in Manchester, NH as shooting locations.

Production scrappiness aside the most important part of that process was the writing. Time being money and all we knew we weren’t going to have the chance to improvise a bunch on set and do a bunch of takes. There were a few opportunities to do a little of that i.e., Matt Walsh’s scene with Jon Lutz at the office party late in the movie or Bobby Moynihan’s scenes in the supermarket, but at that point it’s not like you’re rolling for ten minutes hoping somebody will find what’s funny about the scene. You already have something serviceable written and are just watching a couple genius actor-improvisers make it even better like five times in a row and then you get to pick the best one. Going into it with a script where the story, characters, and especially jokes were all solid on the page was key. A lot of that was down to Dan and Meggie’s sense of what was feasible and achievable on a production level — and it deserves to be said, Dan’s ambition and visual sense really kind of made the videos and movie what they were in many ways, and Meggie figuring out how we could actually do stuff in a professional way really none of us were qualified to do in our late teens and early, early 20s — combined with Donald‘s experiences writing for 30 Rock that very much set the tone and the bar for the writing process.

And as for the casting, as you mentioned, we were really just pulling from people in the UCB community in New York that we were part of at that time. It was an incredibly cool scene to be a part of, and I’m still super grateful for it.

RC: That was right at the beginning of the social-media age, and you’ve leveraged several platforms for comedic purposes. Have you had a plan for those or do you just improvise as needed?

DCP: Ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha, no. It’s more like just keep swimming and try to stay visible. I think I took to Twitter because for better or for worse, I like wordplay and obscure pop culture references, and those both happened to be things that were valuable in that medium. It’s been a slower time adjusting to things like Instagram and TikTok, but I think I’m getting there now especially since I’ve decided to embrace making essentially short short solo sketch videos. It’s a combination of where the technology’s at, that I can just make them and edit them on my phone and the computer and don’t have to be terrifically skilled, with the fact that I come from a sketch background. And even though I don’t think it will become as bigger universal as Twitter was in a day, I am having a lot of fun on Bluesky, which is largely a text based platform like Twitter. We’ll see how it plays out, but at the moment it has a good community vibe.

I also have to say I share a certain weariness. A lot of people who are freelancers of various stripes, be they visual artists or actors or journalists or Drag performers of constantly having to schlep our wares from platform to platform, most of which seem Paternally hostile to promotion of any kind, even though we’re told that’s what we have to do and to be honest it is what we have to do. I guess in my case, maybe it karmically balances out because what we were making in DERRICK really did come along exactly the right time for how small YouTube was but that it existed at all. Granted, none of these things were as developed or capricious or even pernicious as they are these days and maybe that’s part of what was so lucky.

RC: You’ve been very prolific, and your newsletter is especially erudite and hilarious. Do you publish or perform everything you come up with, or do you save some things for longer or larger releases?

DCP: Thank you! I have fun doing it, but haven’t done it as much in the last year for various scarcity of bandwidth reasons. I would say in all forms I probably execute like 10% of the ideas I come up with, but that might be a very generous definition of the word idea. I also think — and here I’m quoting Tom Scharpling, author and host of The Best Show who I think is quoting someone else from his life: The execution is really all that matters, ideas are cheap. Of things I actually execute, like write a draft or shoot some of, most of those get out there. I’m not sitting on like a giant archive of unpublished work, though weirdly network effects and internet attention spans being what they are, it’s kind of like anyone who makes things is sitting on a giant archive of unpublished work because it seems like if you’re not constantly surfacing your own stuff, the kind of attention span Eye of Sauron immediately moves off of them. That said, I do have a an essay about going to see the Postal Service and Death Cab like a year ago that I wrote around that time and just never sent out for whatever reason, so thanks for the reminder.

Oh also, even as I say that I have a rough draft of a new book completed, and I need to like lower myself into the whale carcass of that at some point and finish it. More than anything it’s just a debt of honor I owe myself at this point.

RC: “Execution over ideas.” Did you find that as hard to hear as I did?

DCP: Oh, for sure! And if you’re like me — which we all are, in this way — you’re getting older. So if you think about it for two seconds, or stop trying not to think about it, you realize that the horizon for doing all the ideas is getting smaller. That’s a panicky feeling but there’s also something freeing about it. Less time for doing things that seem like a generically good idea rather than the most You idea, the thing that you’re the most excited about.

RC: Your books were the next thing I was going to ask about. I don’t agree with them, but writers always seem to talk about how hard and thankless it is. Do you enjoy the practice of writing?

DCP: I do! I think I’ve even gotten quasi defensive of it in the post ChatGPT era — like, as long as we’ve been putting pen to paper or pushing the cursor forward writers have been complaining about the drudgery and the solitude of writing, and now all the sudden all these tech bros are coming out of the woodwork claiming to have “solved” it and it’s like, hold on — that’s our solitude and drudgery! It’s like the line from some 90s kids movie — “nobody hits my brother but me!”

There was a line in Top Gun: Maverick that resonated with me (a lot actually! I loved that movie!) about how even with all this modern war-fighting technology, success or failure in one of these insane dogfights those Top Gun rascals are always getting themselves into still comes down to “the man in the box,” i.e., the human being in the really expensive fighter plane. The movie is a really thinly veiled metaphor for Cruise’s own feelings about old-fashioned movie craftsmanship and exhibition vs. the new degraded and rapidly diminishing versions of those things, feelings I happen to strongly share, so that helped. But also, the phrase immediately resonated with me as a good way to explain that ineffable and sometimes frustrating feeling of being a writer who is actually sitting down and writing.

I also have done a fair amount of writing for award shows and things, and when I got to the point where I was head-writing the shows, I realized what a lot of people who’ve done something long enough to ascend into a quasi-management position learn: You get separated from the thing you love that got you there in the first place. I would spend 99% of my time delegating or fielding emails from other people in charge of other parts of the show or in meetings or on calls. I’d be desperate to have time to just sit down and bang out drafts of things we needed for the show but wouldn’t really be able to. Unfortunately (or fortunately) I think I’m pretty good at all that other stuff too, but it’s way less specialized. A gajillion people can type “circling back” in an email window. Not everybody can be (or wants to be) the proverbial Man in the Box. Also the world will intercede in infinite ways to keep you from being that (hu)Man. That line in the Top Gun sequel was a good reminder to try and maximize my time in the box.

RC: My parents were never into music and subsequently have never really understood my life-long love and interest in it. You had a very different experience. Can you tell me a little about that?

DCP: Dang!! Well I’m sorry it wasn’t something you grew up with in the house very much but it doesn’t seem to have stopped you getting immersed in it — maybe because it was something you had to actively seek out or used to define yourself as a separate entity. (That unsolicited uncredentialed faux-therapy will be $125, please). I didn’t grow up in a musical household the same way many friends of mine who themselves are way more “musical,” as in, playing instruments or singing, did — like, it wasn’t a thing where my mom played piano or my dad and uncle would get guitars out and jam at family gatherings. But my parents were both pretty typical boomers (complimentary, in this instance) in that they both had really close relationships to the music they grew up on (The Beatles in my mom’s case and 70s rock in my dad’s) and my dad maintained an active interest in new music his whole life (my mom probably would’ve as well but she died when I was 12 — you can actually just repay me in some therapy about that).

The times I’m most grateful for now, as I wrote about in this essay, are evenings when I’d be visiting home as an adult and some combination of me, my dad, and my brothers would hang out on the couch in the living room in front of my dad and stepmom’s state-of-the-art-at-the-time home entertainment system and switch off playing songs from our laptops. It was a lucky collision of where the technology was at — the peak iPod / iTunes era — and where we were at in our lives as father and adult / college / older teenage sons, and a lot of emotional conversations that might not have happened otherwise were had. Those are the times I most value and the thing I’d most like to have back, though my dad’s gone now too. ROY, MAKE WITH THE THERAPY, PLEASE!!

It’s funny, I’ve been realizing recently that some music has gone from “this reminds me of my dad” — like, folky, quasi-ambient Windham Hill records or cool jazz played by white dorks who looked like NASA engineers — to “this is just music I like and actively want to seek out.” They say you become your parents and if this a form it takes for me, great. I will be listening to some of the mellowest shit of all time.

RC: What else is coming up in the DC Universe?

DCP: So much, I hope! Continuing to work on a feature script adaptation of my first book The Boy Who Couldn’t Sleep And Never Had To with my pals Dan Eckman and Meggie McFadden. It’s a process that’s had various fits, starts, and tantalizing near-misses with fruition over the years — and along we made this proof of concept short that still rules imo — and it’s at a phase where it’s the most exciting it’s been a long time <knock on wood>.

I’m working on a live show with my very talented writer, actor friend Robbie Sublett that I’m also super excited about. It kind of ties in with exactly where we are in our lives and careers while also — hopefully — having a hook that gets people in the door. To be announced on that front.

I’ve also been posting a lot more short comedy videos to Instagram and TikTok and such, particularly a series where I play “The Architect Who Designed New York,” basically an excuse to walk around and make short, silly, one-liners I can then cut together based around stuff I see. Been really enjoying that. Every time I set out to shoot one I end up with enough material for almost two, so it keeps rolling.