During the last episode of season four of True Detective, some cheered and others groaned when Raymond Clark said “time is a flat circle,” repeating Reggie Ledoux and Rustin Cohle’s line from season one. OG creator and showrunner Nic Pizzolato himself did not appreciate the homage to the original. Allusions as such can go either way.

At their best, allusions add layers of meaning to our stories, connecting them to the larger context of a series, genre, or literature at large. At worst, they’re lazy storytelling or fumbling fan service. It feels good to recognize an obscure allusion and feel like a participant in the story. It feels cheap to recognize one and feel manipulated by the writer. They are contrivances after all: legacy characters, echoed dialog, recurring locations or props—all of these can work either way, to cohere or alienate, to enrich the meaning or pull you right out of the story.

[WARNING: Spoilers abound below for all seasons of HBO’s True Detective.]

Our experience with a story is always informed by our past experience—lived or mediated—but when that experience is directly referenced with an allusion, we feel closer to the story. Allusions are where we share notes with other fans, and they form associative paths, connecting them to other artifacts. So, if you recognized Ledoux or Cohle’s words coming out of Clark’s mouth, or if you recognized all of them as Friedrich Nietzsche’s eternal recurrence, you probably felt a closer tie to the story. As he wrote in The Gay Science (1882), “Do you want this again and innumerable times again?” For Nietzsche, this is all there was, and to embrace this recurrence was to embrace human life just as it is: the same thing over and over.

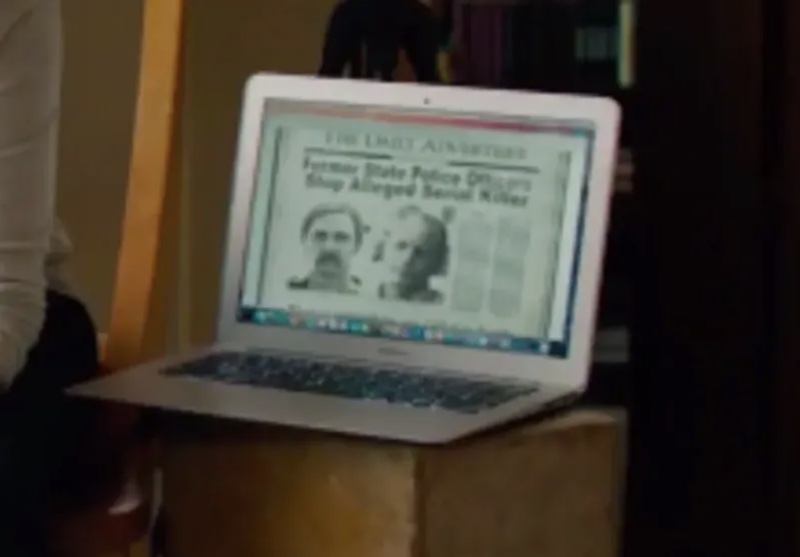

Moreover, in season four we got the ghost of Rust Cohle’s father, Travis Cohle, a connection to the vast empire of the Tuttle family, and the goofy gag of recurring spirals. Season three had its passing connections to season one as well, as seen in the newspaper article in the image above. Given the pervasive references to it, season one may have been the show’s peak, but my favorite is still the beleaguered second season, the only one so far that stands free of allusions to the other seasons of the anthology. Perhaps it is the most hated season of the series because of its refusal to connect to and coexist with the others, yet—riding the word-of-mouth wave from season one—it’s also the most watched.

It should be noted that in addition to its lack of allusions to season one and any semblance of interiority, season two also lacks any sense of the spiritual. There is only the world you see and feel in front of you, no inner world, no adjacent beyond, no Carcosa. As Raymond Velcoro says grimly, “My strong suspicion is we get the world we deserve.”

Season two continues the gloom of the first season, moving it from the swamps of Louisiana to the sprawl of Los Angeles. Like its suburban setting, season two stretches out in good and bad ways, leaving us by turns enlightened and lost. Though, as Ian Bogost points out, where Cohle got lost in his own head, the characters in season two—Ani Bezzerides, Paul Woodrugh, Frank Semyon, and Velcoro—get lost in their world. The physician and psychoanalyst Dr. John C. Lilly distinguished between what he called insanity and outsanity. Insanity is “your life inside yourself”; outsanity is the chaos of the world, the cruelty of other people. Sometimes we get lost in our heads. Sometimes we get lost in the world.

To be fair, season one isn’t without its references to existing texts. Much of the material in Cohle’s monologues is straight out of Thomas Ligotti’s The Conspiracy Against the Human Race (Hippocampus Press, 2010), where he quotes the Norwegian philosopher Peter Wessel Zapffe (even using the word “thresher” to describe the pain of human existence), and the dark-hearted philosophy of Nietzsche, of course. The writings of Ambrose Bierce (“An Inhabitant of Carcosa”), H.P. Lovecraft (Cthulhu Mythos), and Robert W. Chambers (“The Yellow King”) also make appearances. Daniel Fitzpatrick writes in his essay in the book True Detection (Schism, 2014), “Through these references, engaged viewers are offered a means to unlock the show’s secrets, granting a more active involvement, and while these references are often essential and enrich our experience of the show, in its weaker moments they can make it seem like a grab-bag of half thought-through allusions.”

“One of the things that I loved most about that first season of True Detective was the cosmic horror angle of it,” says season four writer, director, and showrunner Issa López. “It had a Carcosa, and it had a Yellow King, which are references to the Cthulhu Mythos with Lovecraft and the idea of ancient gods that live beyond human perception.” The hints of something beyond this world, “the war going on behind things,” as Reverend Billy Lee Tuttle put it, pulled us all in. “That sense of something sinister playing behind the scenes, and watching from the shadows,” she continues, “is something that I very much loved.”

In his book on suicide, The Savage God (1970), Al Álvarez writes, “For the great rationalists, a sense of absurdity—the absurdity of superstition, self-importance, and unreason—was as natural and illuminating as sunlight.” By the end of season one, Rustin Cohle seems to embrace the eternal recurrence of his life, the spiral of light and the dark—including his own daughter’s death. At the end of Night Country, Evangeline Navarro seems to do the same, walking blindly into extinction, one last midnight, a lone sister, fragile and numinous, opting out of a raw deal, lost both in her head and in the world.

Further Reading:

David Benatar, Better Never to Have Been: The Harm of Coming Into Existence, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Ambrose Bierce, Ghost and Horror Stories of Ambrose Bierce, New York: Dover, 1964.

Ray Brassier, Nihil Unbound: Enlightenment and Extinction, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

Robert W. Chambers, The King in Yellow, Knoxville, TN: Wordsworth Editions, 2010.

Roy Christopher, Escape Philosophy: Journeys Beyond the Human Body, Brooklyn, NY: punctum books, 2021.

Edia Connole, Paul J. Ennis, & Nicola Masciandaro (eds.), True Detection, Schism, 2014.

Jacob Graham & Tom Sparrow (eds.), True Detective and Philosophy: A Deeper Kind of Darkness, Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2018.

Thomas Ligotti, The Conspiracy Against the Human Race, New York: Hippocampus Press, 2010.

Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science, New York: Dover, 1882.

Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spake Zarathustra: A Book for All and None, New York: Macmillan. 1896.

Nic Pizzolatto, Between Here and the Yellow Sea, Ann Arbor, MI: Dzanc Books, 2015.

Eugene Thacker, In the Dust of This Planet: Horror of Philosophy, Vol. 1, London: Zer0 Books, 2011.

Eugene Thacker, Infinite Resignation, London: Repeater Books, 2018.