After looking back at the unified election map from 1984 and griping about advertising again, I arrived this week on their intersection: Apple’s 1984 Super Bowl commercial introducing the Macintosh. It launched not only the home-computer revolution but also the Super Bowl advertising frenzy and phenomenon.

The commercial burned itself right into my brain and everyone else’s who saw it. It was something truly different during something completely routine, stark innovation cutting through the middle of tightly-held tradition. I wasn’t old enough to understand the Orwell references, including the concept of Big Brother, but I got the meaning immediately: The underdog was now armed with something more powerful than the establishment. Apple was going to help us win.

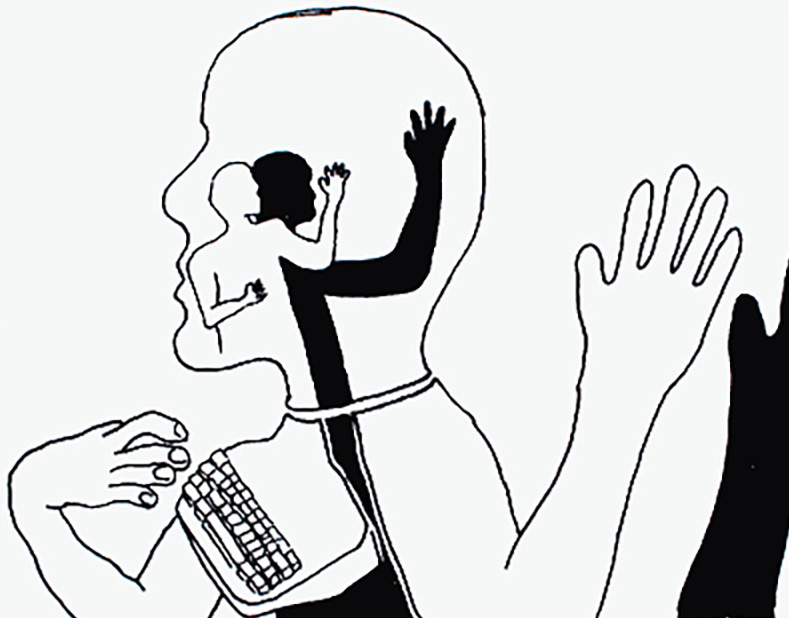

Apple has of course become the biggest company in the world in the past 40 years, but reclaiming the dominant metaphors of a given time is an act of magical resistance. Feigning immunity from advertising isn’t a solution, it provides a deeper diagnosis of the problem. Appropriating language, mining affordances, misusing technology and other cultural artifacts create the space for resistance not only to exist but to thrive. Aggressively defying the metaphors of control, the anarchist poet Hakim Bey termed the extreme version of these appropriations “poetic terrorism.” He wrote,

The audience reaction or aesthetic-shock produced by [poetic terrorism] ought to be at least as strong as the emotion of terror—powerful disgust, sexual arousal, superstitious awe, sudden intuitive breakthrough, dada-esque angst—no matter whether the [poetic terrorism] is aimed at one person or many, no matter whether it is “signed” or anonymous, if it does not change someone’s life (aside from the artist) it fails.

Echoing Bey, the artist Konrad Becker suggests that dominant metaphors are in place to maintain control, writing,

The development in electronic communication and digital media allows for a global telepresence of values and behavioral norms and provides increasing possibilities of controlling public opinion by accelerating the flow of persuasive communication. Information is increasingly indistinguishable from propaganda, defined as “the manipulation of symbols as a means of influencing attitudes.” Whoever controls the metaphors controls thought.

In a much broader sense, so-called “culture jamming,” is any attempt to reclaim the dominant metaphors from the media. Gareth Branwyn writes, “In our wired age, the media has become a great amplifier for acts of poetic terrorism and culture jamming. A well-crafted media hoax or report of a prank uploaded to the Internet can quickly gain a life of its own.” Culture jammers, using tactics as simple as modifying phrases on billboards and as extensive as impersonating leaders of industry on major media outlets, expose the ways in which corporate and political interests manipulate the masses via the media. In the spirit of the Situationists International, culture jammers employ any creative crime that can disrupt the dominant narrative of the spectacle and devalue its currency.

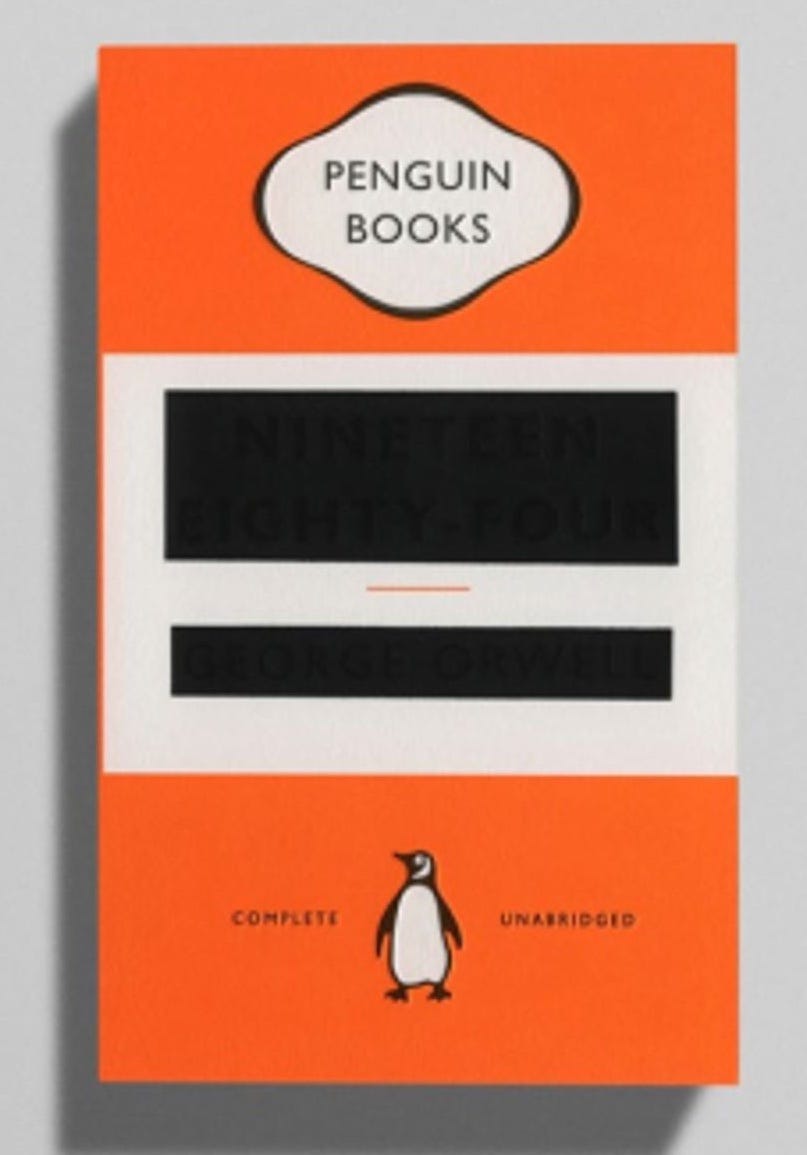

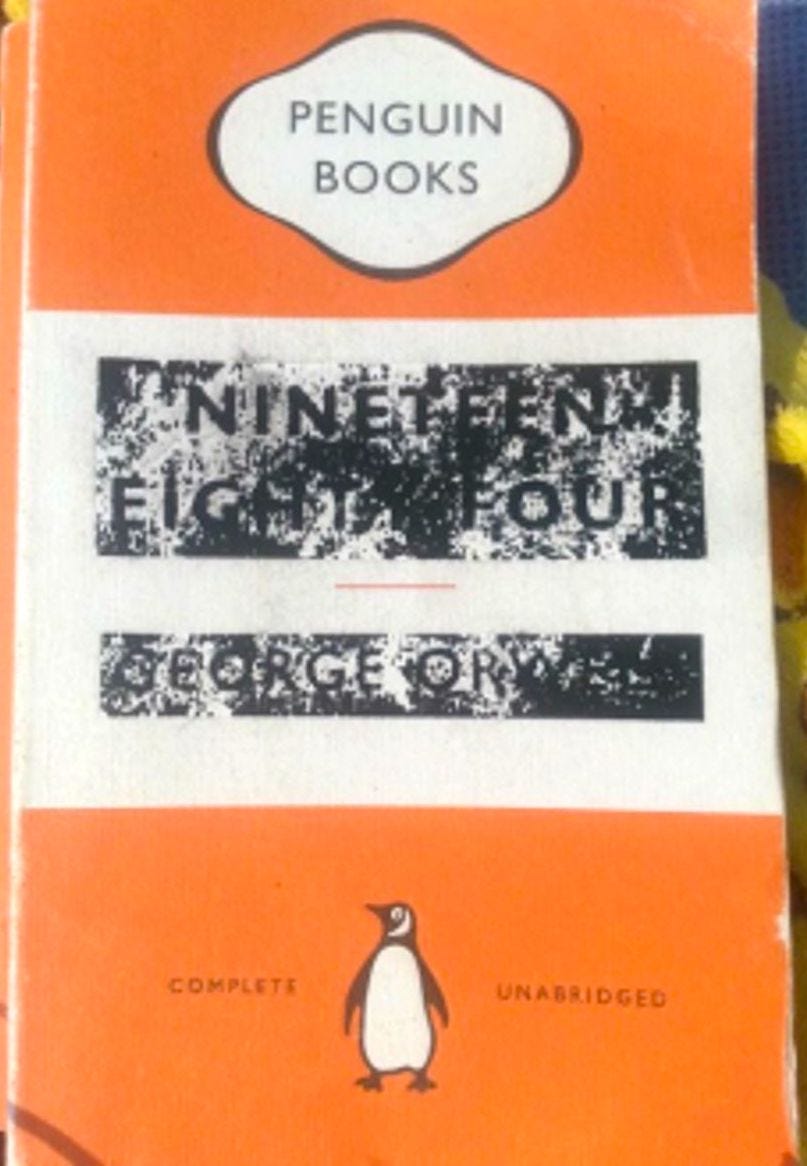

“If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face—forever.”

— George Orwell, 1984

“It’s clearly an allegory. Most commercials aren’t allegorical,” OG Macintosh engineer Andy Hertzfeld says of Apple’s “1984” commercial. “I’ve always looked at each commercial as a film, as a little filmlet,” says the director Ridley Scott. Fresh off of directing Blade Runner, which is based on a book he infamously claims never to have read, he adds, “From a filmic point of view, it was terrific, and I knew exactly how to do a kind of pastiche on what 1984 maybe was like in dramatic terms rather than factual terms.”

David Hoffman once summarized Orwell’s 1984, writing that “during times of universal deceit, telling the truth becomes a revolutionary act.” As the surveillance has expanded from mounted cameras to wireless taps (what Scott calls, “good dramatic bullshit”; cf. Orwell’s “Big Brother”), hackers have evolved from phone phreaking to secret leaking. It’s a ratcheting up of tactics and attacks on both sides. Andy Greenberg quotes Hunter S. Thompson, saying that the weird are turning pro. It’s a thought that evokes the last line of Bruce Sterling’s The Hacker Crackdown which, after deftly chronicling the early history of computer hacker activity, investigation, and incarceration, states ominously, “It is the End of the Amateurs.”

These quips could be applied to either side.

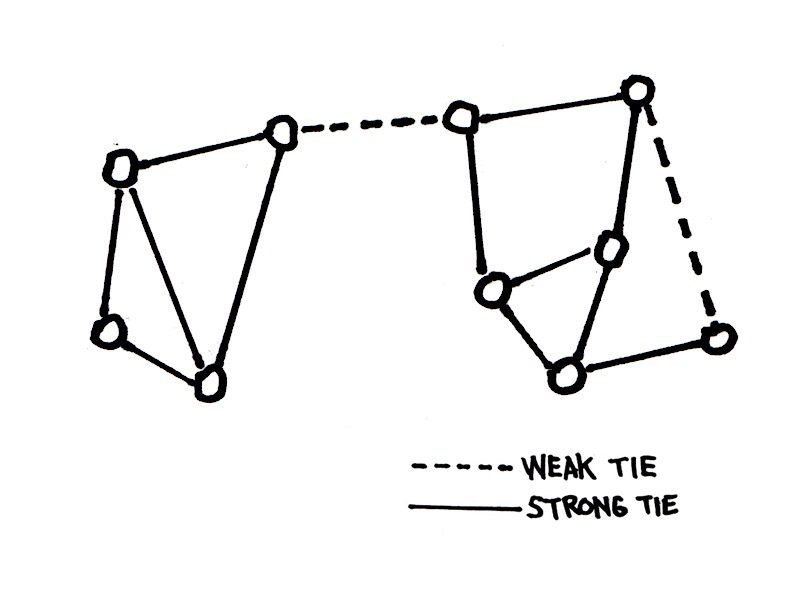

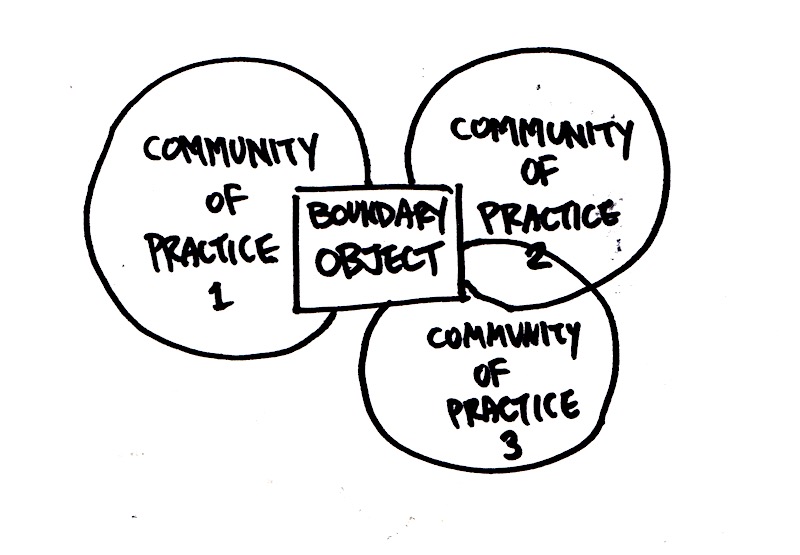

The Hacker Ethic—as popularized by Steven Levy’s Hackers (Anchor, 1984)—states that access to computers “and anything which might teach you something about the way the world works should be unlimited and total” (p. 40). Hackers seek to understand, not to undermine. And they tolerate no constraints. Tactical media, so-called to avoid the semiotic baggage of related labels, exploits the asymmetry of knowledge gained via hacking. In a passage that reads like recent events, purveyor of the term, Geert Lovink writes, “Tactical networks are all about an imaginary exchange of concepts outbidding and overlaying each other. Necessary illusions. What circulates are models and rumors, arguments and experiences of how to organize cultural and political activities, get projects financed, infrastructure up and running and create informal networks of trust which make living in Babylon bearable.”

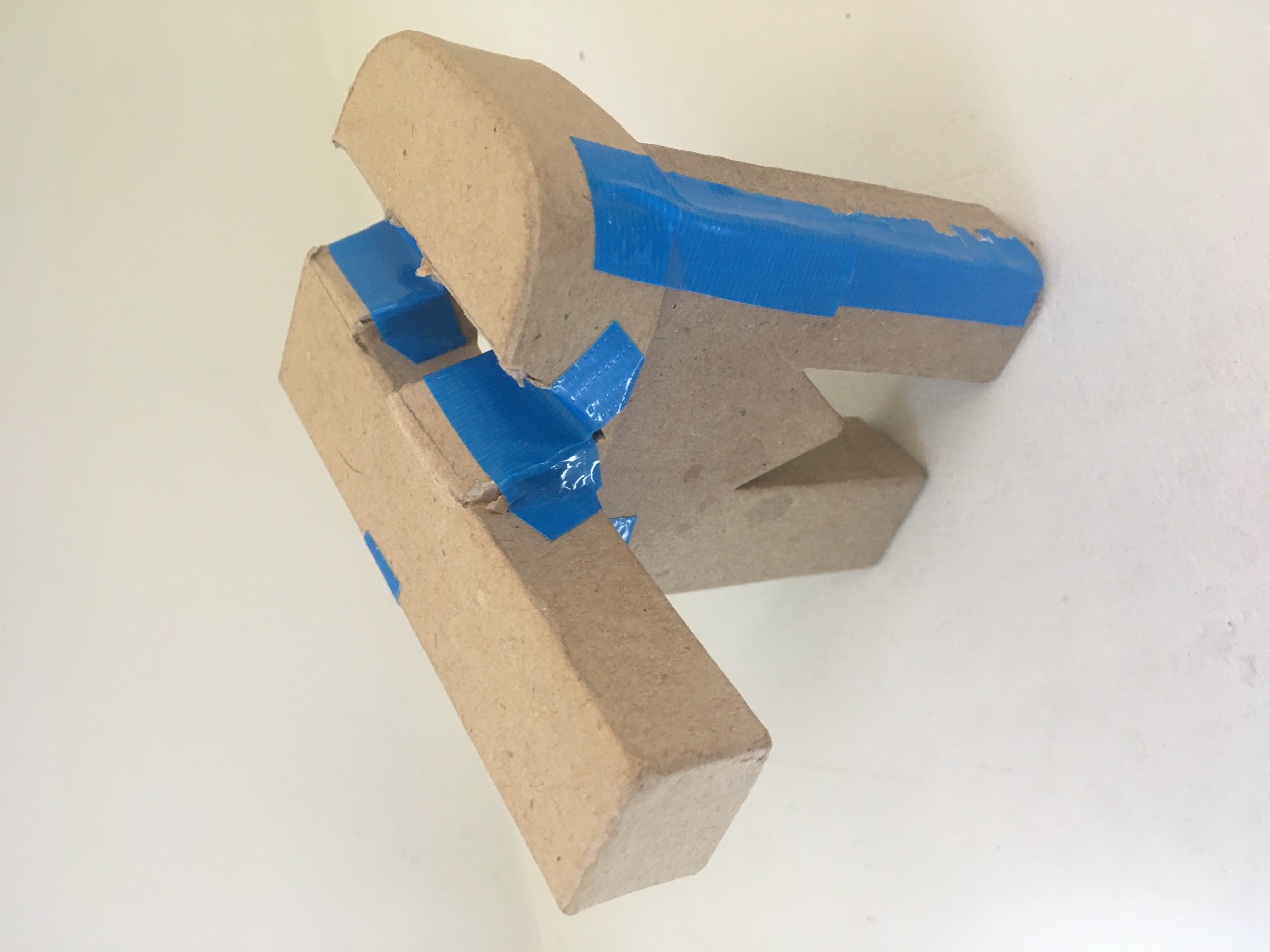

If you want a picture of the future now, imagine a sledgehammer shattering a screen—forever.

Following Matt Blaze, Neal Stephenson states “it’s best in the long run, for all concerned, if vulnerabilities are exposed in public.” Informal groups of information insurgents like the crews behind Wikileaks and Anonymous keep open tabs on the powers that would be. Again, hackers are easy to defend when they’re on your side. Wires may be wormholes, as Stephenson says, but that can be dangerous when they flow both ways. Once you get locked out of all your accounts and the contents of your hard drive end up on the wrong screen, hackers aren’t your friends anymore, academic or otherwise.

Hackers of every kind behave as if they understand that “[p]ostmodernity is no longer a strategy or style, it is the natural condition of today’s network society,” as Lovink puts it. In a hyper-connected world, disconnection is power. The ability to become untraceable is the ability to become invisible. We need to unite and become hackers ourselves now more than ever against what Kevin DeLuca calls the acronyms of the apocalypse (e.g., WTO, NAFTA, GATT, etc.). The original Hacker Ethic isn’t enough. We need more of those nameless nerds, nodes in undulating networks of cyber disobedience. “Information moves, or we move to it,” writes Stephenson, like a hacker motto of “digital micro-politics.” Hackers need to appear, swarm, attack, and then disappear again into the dark fiber of the Deep Web.

Who was it that said Orwell was 40 years off? Lovink continues: “The world is crazy enough. There is not much reason to opt for the illusion.” It only takes a generation for the underdog to become the overlord. Sledgehammers and screens notwithstanding, we still need to watch the ones watching us.