Brian Eno calls him, “The New Gutenberg.” His work tip-toes through the same conceptual gardens as Marshall McLuhan, Ted Nelson, Douglas Englebart, and yes, even Johannes Gutenberg himself. Hypertext (he is one of the principle developers of Storyspace — a standalone Hypertext authoring environment), media evolution and the computer’s role in the writing process as well as education are a few of his points of interest. His books include Turing’s Man, Remediation: Understanding New Media (with Richard Grusin) and the absolutely essential Writing Space: Computers, HyperText, and the History of Writing.

Brian Eno calls him, “The New Gutenberg.” His work tip-toes through the same conceptual gardens as Marshall McLuhan, Ted Nelson, Douglas Englebart, and yes, even Johannes Gutenberg himself. Hypertext (he is one of the principle developers of Storyspace — a standalone Hypertext authoring environment), media evolution and the computer’s role in the writing process as well as education are a few of his points of interest. His books include Turing’s Man, Remediation: Understanding New Media (with Richard Grusin) and the absolutely essential Writing Space: Computers, HyperText, and the History of Writing.

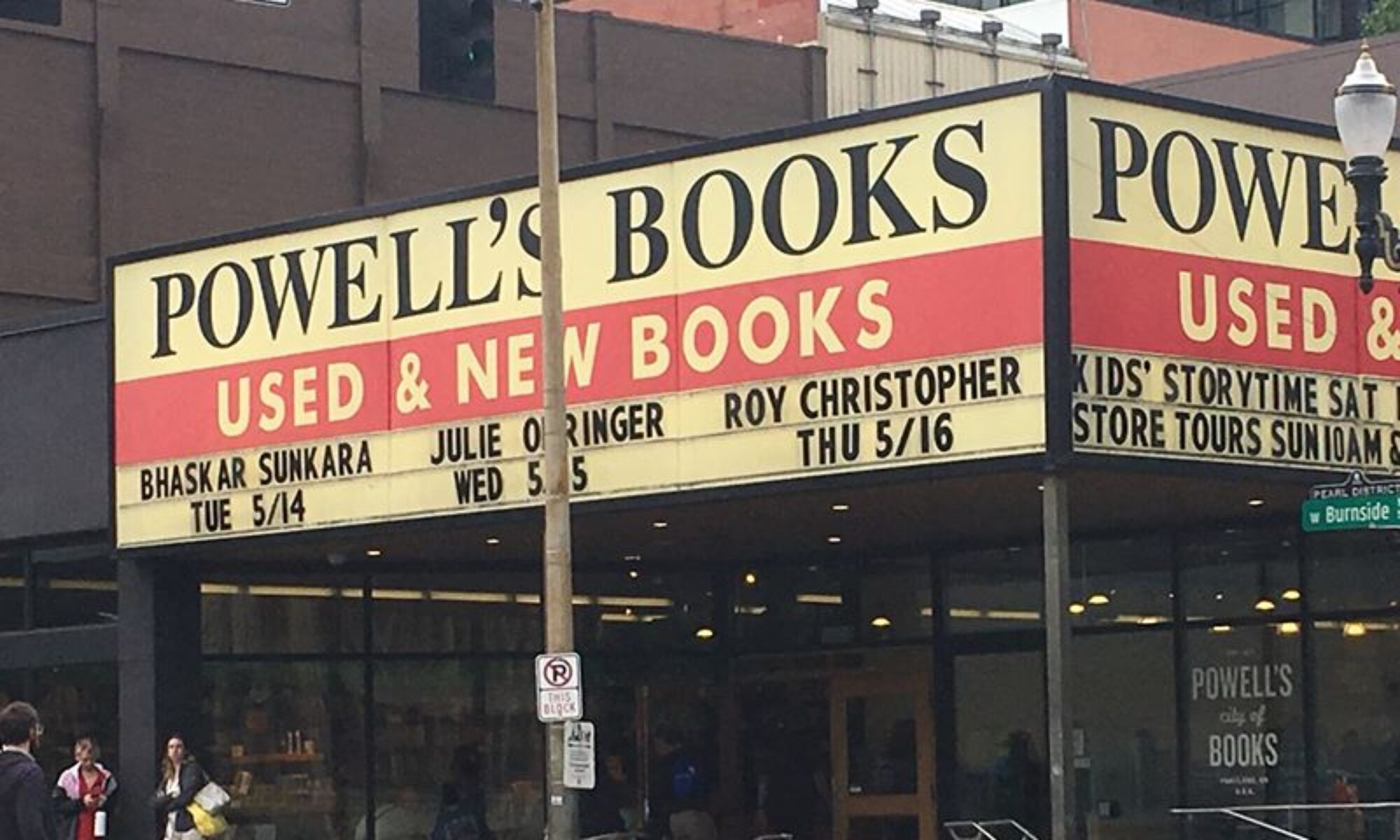

Roy Christopher: The web has provided an environment for the high-speed spread and exchange of information. Do you think it has evolved in the best possible manner? What could we be doing better on and with the internet’s power?

Jay David Bolter: The World Wide Web is an extraordinary achievement. It isn’t just about the exchange of information, narrowly conceived as bytes of data. It has already spawned a whole set of new media genres and forms: news and information sites, personal home pages, corporate sites for marketing and sales, entertainment sites, gambling and pornography sites, and the sometimes tedious, sometimes amazing webcams. The Web is now suffused with the influence of global capitalism, and for that reason alone it has become an object of critique for many in media studies. The Web has also disappointed the relatively small, but dedicated community of writers who were creating standalone or small networked hypertexts in the 1980s and early 1990s. Many of their systems were more sophisticated than the Web in the sense that they offered better linking protocols and more possibilities for author/reader interaction. Nevertheless, the Web succeeded in capturing the imagination of our culture where these earlier systems did not. We could certainly propose a more powerful global hypertext system, but the genius of the Web lay in its (originally) simple link structure and its distributed architecture. Everyone could understand how the Web worked – how you traveled from page to page – and anyone with access to a server could create her own Web pages. As soon as inline graphics were added in 1993, the Web had everything it needed to become a cultural and economic phenomenon.

The Web is changing, developing richer forms of interaction. But as everyone who uses the Web is aware, the most important trend is toward increasing use of multimedia forms. Tim Berners-Lee originally conceived of the Web principally as a textual medium. The development of the Mosaic browser in 1993 gave us the Web as a new space for graphic design—the combination of text and static graphics. Now we see animation, digitized video, and sound playing a greater role. This trend will surely continue, even if we don’t see the ultimate ‘convergence’ of television and the computer that some have predicted.

RC: How does Storyspace’s hypertextual environment compare to the concepts in Ted Nelson’s Xanadu project — if at all?

JDB: Storyspace is a standalone hypertext writing system. It was developed by Michael Joyce, John Smith, and myself, and is now being further developed by Mark Bernstein of Eastgate Systems. It never aspired to Nelson’s vision of a global networked hypertext system. (The World Wide Web is the fulfillment of that vision, although in a way that Nelson did not anticipate and of which, I believe, he has disapproved.) Storyspace is a system for creating, editing, and displaying small- to medium-sized hypertexts. It has never had more than a few thousand users. However, I’m proud to say that some of the truly original and important hypertext fictions (including Michael Joyce’s own afternoon, Stuart Moulthrop’s Victory Garden, Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl, and many others) were conceived and executed in Storyspace. The system was designed to support hypertext fiction in particular, although it can also be used for organizing and writing fiction and non-fiction intended for print. (I have used Storyspace to write or revise three of my own books.) Storyspace provides more facilities for writing and editing (it includes a dynamic map of the structure of the links) than for the high-quality display and reading of the eventual hypertext. Many users of Storyspace now choose to export their hypertexts to html format in order to make them available. Although Storyspace is capable of incorporating graphics and digitized video, it has principally been used for verbal hypertexts, and frankly, this emphasis on the word puts Storyspace at a disadvantage as we move into an era of multimedia both on and off the Web.

RC: Hypertext will greatly influence/wholly form the next paradigm of education. Do you agree?

JDB: The influence of hypertext on education will come about because of and through the World Wide Web. It is amazing to me how quickly and easily the computer, the Internet, and the Web are being accepted into American education. Compare the reception of the other ‘new media’ of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries: photography, film, radio, and television. American education has given only a marginal place to these media, and, at least in the case of television, it has been openly hostile. None of these media forms has seriously challenged the textbook as our main educational resource. On the other hand, there is a near consensus that computers belong in schools, that schools should be hooked to the Internet, and that students should be given (censored) access to the Web and in many cases should learn to create their own Web pages. This ‘networking’ of American education may result in a hypertextual style of writing. I think the principal effect, however, will be more emphasis on visual communication: using images in addition to or in place of words. This could be significant, when we remember that American education has been principally verbal for centuries. Learning to read and write (words) has been the center of the educational process. I’m not predicting that verbal literacy will cease to be important, but I do think that visual literacy may began to claim a place in our educational programs.

RC: What have you found when comparing levels of metacognition in linear texts versus hypertext situations?

JDB: On the question of linearity vs. hypertextuality as modes of thinking and learning, I’m an agnostic. I don’t know how we could decide whether associative (hypertextual) or linear thinking is more “natural.” Both hypertexts and linear texts are highly artificial forms of writing. Both have to be learned. The idea that hypertext is natural can be refuted simply by browsing through a random sample of Web sites. We see that people do not find it easy or natural to create good sites — either of the hierarchical or associative kind.

RC: Who do you admire writing about media and/or hypertext these days?

JDB: I always admire the work of my collaborator, Michael Joyce, and in particular the second volume of his collected essays, Othermindedness. I admire George Landow’s Hypertext 2.0, which remains the standard work on the subject. Meanwhile, there is a great deal of exciting work being done in new media studies. I’ll just mention two: Janet Murray’s Hamlet on the Holodeck and a new book by Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media.

Among electronic works, I admire M. D. Coverly’s Califia. I’m also impressed by work that does not follow the now traditional hypertextual paradigm. I mean, for example, the kinetic poetry of John Calley and the digital installations and creations of Mark Amerika. My colleague Diane Gromala, a digital artist and theorist, is doing fascinating work in with biosensing equipment to create a kind of animated writing that she calls ‘biomorphic typography.’

RC: Do you have any upcoming projects you’d like to tell us about?

JDB: My colleague Diane Gromala was the director of the SIGGRAPH 2000 Art Gallery. Together we are working on a book on the importance of digital art, which is providing us with new answers to the question: what are computers good for? The artists at SIGGRAPH 2000 were mapping the range of possible digital experiences. Their work provides important clues to the new era of digital design that we are entering.