I used to work as a juvenile rehab counselor at a maximum security facility in Washington state. There were third-generation gang members locked up there, caught in the crossfire where the rules and mores they’d grown up with clashed with those of the larger society.

Last summer, I decided to play identity politics with a new t-shirt purchase. I got myself a Run-DMC shirt. Now, I thought I was paying tribute to one of the original iconic groups of true-school Hip-hop. As it turns out, most people think of Run-DMC as a relic of the 80s. My roommate thought my wearing the shirt was “hilarious.”

Last summer, I decided to play identity politics with a new t-shirt purchase. I got myself a Run-DMC shirt. Now, I thought I was paying tribute to one of the original iconic groups of true-school Hip-hop. As it turns out, most people think of Run-DMC as a relic of the 80s. My roommate thought my wearing the shirt was “hilarious.”

Both of these examples got me thinking about contextual modes of culture. If one grows up in a milieu where mom, dad, granddad and so on are gangsters who do gangster things, then gangster things will be one’s norm. Society’s rules will be secondary. The small picture trumps the larger one in the individual’s mind, no matter what the laws and the police say.

The same goes for my Run-DMC shirt. If I were to wear such a t-shirt to a Hip-hop outing, say a Sean Price show, the people in attendance would get it. They’d know I was paying homage to one of the pioneers of modern Hip-hop culture. If one of the dedicated heads there had brought along a non-fan or a new one (or perhaps a young one), the reference might be misplaced or lost on them.

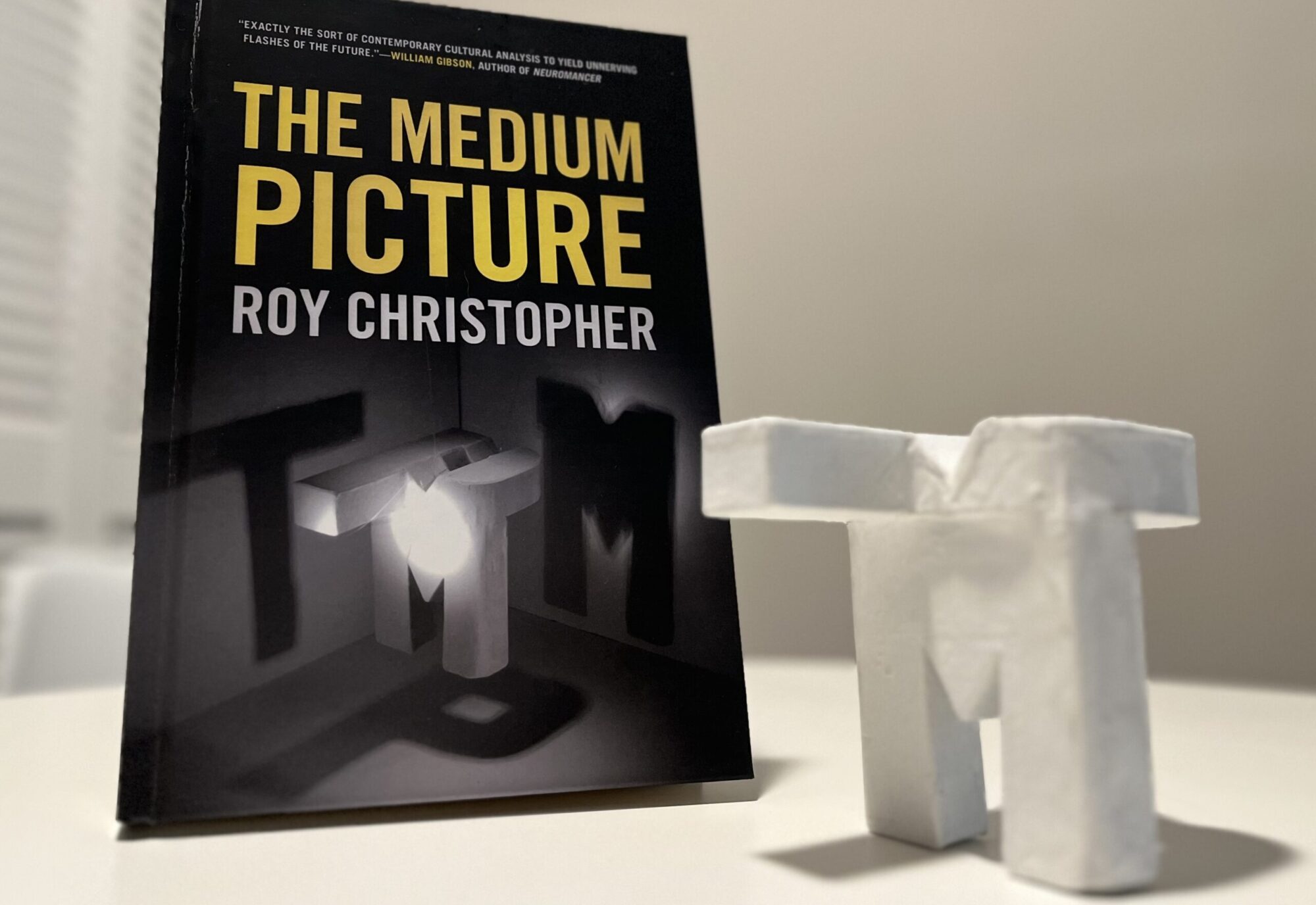

The outlines of the circles in this diagram are the rules, mores, or customs of the cultures and its inclusive subcultures, and the Artifact in my story above is the Run-DMC t-shirt.

A few weeks after my roommate first laughed at me for wearing the shirt, he texted me from an 80s-themed party, saying that the DJ — playing both contexts — was wearing the same t-shirt.

Consider the following rather long-winded example:

In the fall of 1986, I went to my first big BMX event. It was a nationally sanctioned contest and all of the big pros of the time were there. I met and had my picture taken with Dennis McCoy, Ron Wilkerson, Rick Moliterno, Dave Nourie, and many others. As a fifteen-year-old BMX kid, I was geeked… But most of you reading this are saying, “Who?!”

In the summer of 1996, I took over the Editor position at a music magazine in Tacoma, Washington called Pandemonium!. For the cover of my first issue as editor, I managed to arrange an interview with Tori Amos. More pleased about this I could not be… But when I excitedly told a group of my BMX friends about it, they all said, “Who?!”

[By the way, does the culture at large consider BMX an 80s phenomena as well?]

I got three-oh-fours in three-one-oh on section eight, with multiple one-eighty-sevens

Sport a Marilyn Manson t-shirt when I die and go to heaven — Ras Kass (from Xzibit’s “3 Card Molly”)

What about the more deliberate placing of an artifact in a context? For example, Hip-hop acts wearing rock t-shirts. Juicy J of the Three 6 Mafia proudly displays his Iron Maiden t-shirt in the photo below.

Intended irony notwithstanding, this is “different” attire for an emcee. It bucks what is expected from the look of your average rapper (a cursory flip through any Hip-hop magazine will give one a clear impression of the look to which I’m referring), and it’s a juxtaposition of genre signifiers that is totally dependent on context. Outside of Hip-hop, Juicy J is just a guy in a rock t-shirt, but within his “home” context of Hip-hop, he’s making a statement (albeit a statement the Beatnuts made over a decade prior). The context through which it is interpreted determines the meaning of his statement.

KRS-One once said that when it ceases to be rebellious, it ceases to be Hip-hop, but where is the rebellion directed? The context often determines the target.

Culture is contextually modal, and there is often a tension between the rules of a subculture and its attendant culture. Sometimes the tension snaps under the conflict of the two. Sometimes its just fun to play with. The contextual mode of any artifact or rule can be interpreted from within or without its intended mode. The rules of your neighborhood might conflict with the rules of your city. The people you look up to as celebrities might not even be known to your friends. Your default MySpace photo is seen in one way by people who actually know you, and in a completely different way by people who don’t. The same can be said for your Iron maiden t-shirt or my Run-DMC t-shirt. Sometimes they’re just identity politics, but we all play them everyday.