I was raised by record stores. That’s where I went when my mom was grocery shopping or whatever. I was in Peaches or Coconuts or Camelot or whatever suburban chain had the racks. It was a childhood of digging in the crates, gawking at album covers, and occasionally buying a 12×12 cellophane square to take home, open, and spin.

I was raised by record stores. That’s where I went when my mom was grocery shopping or whatever. I was in Peaches or Coconuts or Camelot or whatever suburban chain had the racks. It was a childhood of digging in the crates, gawking at album covers, and occasionally buying a 12×12 cellophane square to take home, open, and spin.

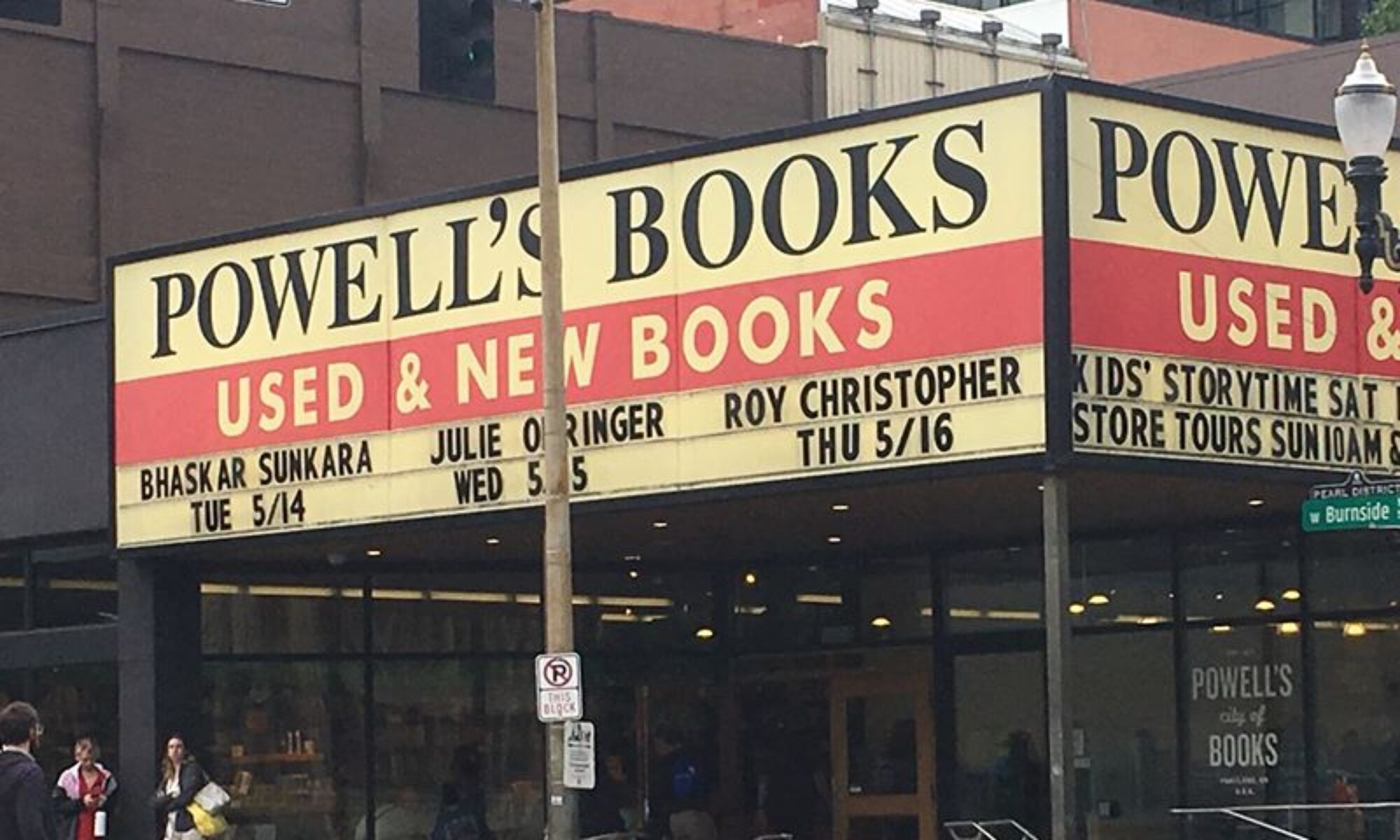

I still frequent record stores. And bookstores. I feel crazy if I go a week without perusing the shelves of one or the other. It’s not nostalgia — I buy CDs only to take them home and rip them to MP3s, but there’s a fundamental difference between browsing actual books on physical shelves and browsing their titles in an online database. Not only are the two experiences dissimilar, they’re not related in any way.

I wrote before about the disconnection between certain activities in our mediated lives. Well, the digital revolution is sparking an altogether different strain of separation. In no way do I consider myself a Luddite, and if you’ve been reading long, you know that I’m not, but we’re losing something in our latest move from atoms to bits. Something big. Something we’ll miss later.

Choosing the difference is one thing (i.e., preferring to shop online, downloading MP3s, buying a Kindle, etc.). Having it forced upon us is another. With the latest involuntary seismic shifts in media — the disintegration of the CD market and subsequent closing of retail outlets, the shrinking of magazines and nodding off of newspapers — the changes are now coming without choices.

Yes, I realize that we’ve made these choices in an Adam Smith, “invisible hand” kind of way, but one wonders where these changes will leave us. The disappearance of media choices is one place where small-town America is on the cutting edge (i.e., you either get it at Wal*Mart, travel to the nearest metropolitan area to get it , get it online, or you just don’t get it.).

The prediction of the death of print media has been on the books since TCP/IP, but now that it finally has a body count, panic is around every corner.

In his book On Writing (Pocket, 2001), Stephen King urges aspiring writers to turn off their televisions, writing, “Once weaned from the ephemeral craving for TV, most people will find that they enjoy the time they spend reading. I’d like to suggest that turning off that endlessly quacking box is apt to improve the quality of your life and the quality fo your writing” (p. 148). Not being a snob, but not owning a TV, I can honestly say I get more done without it around (it’s on at my parents’ house whenever anyone is awake). But as Steve Jobs once observed, the two experiences are fundamentally disconnected: We do some things to turn on, and we do others to turn off.

Part of the distinction between types of media is a simple difference between the ways to display certain types of information. Think of an analog gauge versus a digital one. Neither is inherently better than the other. Their value depends on what information you want from them. An analog display is better at showing progress or a difference between values, whereas a digital display is more accurate at a glance. Now think about this difference in the context of storytelling, between a book and a movie. It’s not the whole story, but it’s part of it.

I’m not worried about the newspapers. I haven’t read a newspaper in years. I’m more worried about choice. When Jeff Bezos left Wall Street for Seattle to start Amazon.com, he picked books because when making a decision to purchase a book online and in a store, you can get roughly the same information. That is, you don’t have to try on a book before you buy it. This insight was Bezos’ one bit of genius, but it was also one of the initial ruptures in the latest stage of the evolution of our relationship with our externalized knowledge.

We’ve been externalizing our knowledge since we started speaking and writing on cave walls, but much more recently, as James Carey (1988) pointed out, the telegraph established a major watershed. It separated communication (and thereby information) from transportation. It made information a commodity, a resource not tethered to the physical world. The internet only extended and solidified the transition.

There are several trajectories here, but the main thing I want to point out here is just that: the multifaceted influence of technological mediation. Every change has unintended consequences, and we lose something with every gain. These changes are neither good nor bad, but we should be mindful that they’re happening.

Dig in the racks, browse the shelves, and read magazines — as long as they’re around.

References:

Carey, J. (1988). Communication as culture. New York: Routledge.

Cringely, R. X. (1996). “Triumph of the Nerds: The Rise of Accidental Empires.” New York: Public Broadcasting System.

King, S. (2001). On writing: A memoir of the craft. New York: Pocket Books.

————

Here’s how long a transition like this takes: Check out Steve Newman’s “telepaper” story as broadcast on KRON in San Francisco in 1981 (runtime: 2:17):