Skateboard and BMX zines defined my formative years. Those handmade, photocopied publications were our network of news, stories, interviews, events, art, and pictures. It’s very difficult to describe how an outmoded phenomena like that worked once such epochal technological change, one that uproots and supplants its cultural practices (i.e., the internet), has occurred. FREESTYLIN’ Magazine’s reunion book, Generation F (Endo Publishing, 2008; flip through it at the link), has a chapter called “The Xerox was Our X-Box,” and that title gets at the import of these things. As I said in that very chapter, “Making a zine was always having something to send someone that showed them what you could do, what you were up to, and what you were into. Ours was the pre-web BMX network.”

At best, zines represent a hidden circuit of media, a grassroots exchange of information and ideas that slips through the cracks of popular culture. Zines are power in the hands of the fans. As Mark Lewman, editor of FREESTYLIN’ Magazine and head of Club Homeboy, as well as “Chariot of the Ninja” zine, points out, “The first zine I did once I moved to California was called ‘Homeboy’. I did one issue and some stickers, and it ballooned into a mail-order lifestyle company with 15,000 members, and became one of the first youth culture magazines, a pastiche of art and sport and randomness. So, the power of zines is pretty unlimited as far as I can tell.”

In spite of the proliferation of the internet, zines are not entirely a thing of the past. Every time we do something on our own instead of just taking what’s given to us, we strike a blow to the massive media machine that constantly shoves products and personality down our throats. Making your own zine is not only immeasurably rewarding (ask anyone who’s ever done one), but it gets your point of view out there and incites dialog between readers, riders and other zine-makers that wouldn’t necessarily take place.

Independent journalists wield the power to expose local underground talent as well. There were always obscure riders in sporadic locales ripping like top pros. There are always great bands no one has heard. The way to get them noticed was not to bug out about major magazines’ lack of attention, but to give the magazines a reason to pay attention. As ex-editor of Faction BMX Magazine John Paul Rogers puts it, “Quit bitching and get off your ass and do something about it.”

So, though they’re as much a part of the process anymore, I cannot overstate the importance of the experience of trading and making zines. There’s something to the physicality of the pages in your hand and the focus on those pages that pixels on screens don’t afford. As I said in FREESTYLIN’ Generation F, “Those first issues were the first steps on a path I still follow.”

Still true.

Portable Document Formats:

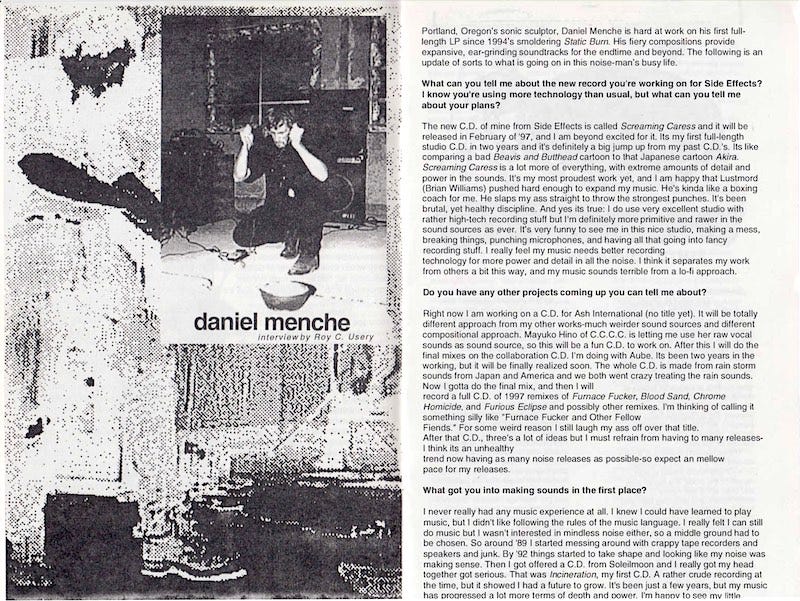

If you’re interested, I scanned and uploaded a couple of my later zines as .pdfs. wow&flutter (1997) was an attempt to bring together experimental noise of all kinds and featured interviews with Daniel Menche, John Duncan, and a cover story about turntablism. It was intended as part of a series, but the second issue, attack&decay, featuring interviews with Jack Dangers of Meat Beat Manifesto and Warren Defever of His Name is Alive, among others, never made it to press. I still love the idea of noise and hip-hop coming together, and there are others who’ve merged them in the meantime better than I could have imagined (e.g., dälek, clipping., Ho99o9, Death Grips, Cloaks, Justin Broadrick and Kevin Martin, et al.)

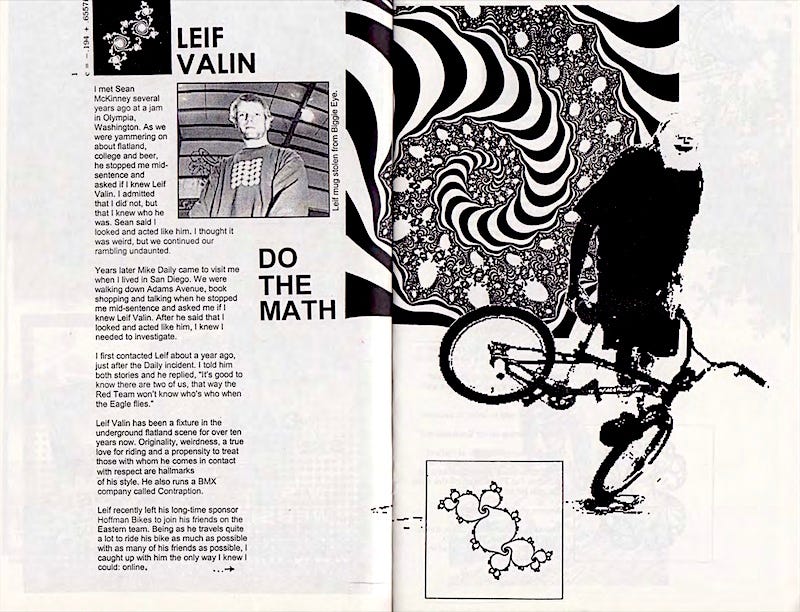

HEADTUBE (2001) was my attempt to return to BMX zine-making while maintaining my other, newfound interests in the early 00s. Though I maintained the website for years after, the zine ended up as another one-off print publication. It features interviews with Seattle ripper Steve Machuga, flatland guru Leif Valin, and the band Milemarker, as well as reviews of books, records, and other media. I still have a few copies of the print version. Let me know if you’re interested.