As usual, the Summer Reading List is the time of year when I ask a bunch of my bookish friends what they’re reading. It’s always a good time, and this year we have newcomers and old friends Howard Rheingold, Michelle Rae Anderson, and Zizi Papacharissi, as well as Summer Reading List vets like Alex Burns, Cynthia Connolly, Steven Shaviro, Ashley Crawford, Peter Lunenfeld, Erik Davis, Michael Schandorf, Patrick Barber, and Brian Tunney.

As usual, the Summer Reading List is the time of year when I ask a bunch of my bookish friends what they’re reading. It’s always a good time, and this year we have newcomers and old friends Howard Rheingold, Michelle Rae Anderson, and Zizi Papacharissi, as well as Summer Reading List vets like Alex Burns, Cynthia Connolly, Steven Shaviro, Ashley Crawford, Peter Lunenfeld, Erik Davis, Michael Schandorf, Patrick Barber, and Brian Tunney.

As always, the book links on this page will lead you to Powell’s Books, the best bookstore on the planet, except where noted otherwise. Read on.

Howard Rheingold

I’m re-reading J. Stephen Lansing’s Perfect Order: Recognizing Complexity in Bali (Princeton University Press, 2006) as part of my continuing research into cooperation studies. The water temple system in Bali is a complex, beautiful, and remarkably effective social and ecological management system that is coordinated through rituals that neatly solve water-sharing social dilemmas that vex much of the planet.

Also, Robert K. Logan’s The Extended Mind: The Emergence of Language, the Human Mind, and Culture (University of Toronto Press, 2007) as part of my research into the possibility that [using] the Web [mindfully] might actually [help] make people smarter.

Alex Burns

Jeanne De Salzmann The Reality of Being: The Fourth Way of Gurdjieff (Shambhala, 2010): De Salzmann (1889-1990) preserved the writings and movements of the Graeco-Armenian teacherGeorge Gurdjieff, and founded groups in New York, London, Paris, and Caracas. The Reality of Being articulates her unique, ’embodied’ perspective on the Fourth Way, drawing on forty years of reflective notebooks. De Salzmann wrote: “Man remains a mystery to himself. He has a nostalgia for Being, a longing for duration, for permanence, for absoluteness–a longing to be.”

Ronald A. Havens The Wisdom of Milton H. Erickson: The Complete Volume (Crown House Publishing, 2009): Erickson (1901-1980) developed clinical hypnotherapy, and influenced neuro-linguistic programming (the Milton model). Through topical study of his writings, Wisdom covers Erickson’s insights about the unconscious mind, therapeutic change, utilisation, and trance induction techniques. A useful overview to the philosophy and methodology of Ericksonian hypnosis.

Charles Hill Grand Strategies: Literature, Statecraft, and World Order (Yale University Press, 2010): Hill is a diplomat who contends that engagement with literature is a way to understand statecraft. Ranging from Homer, Thucydides, and Machiavelli to Milton, Thoreau, Mann, and Rushdie, Hill explores how literature illuminates themes of order, war, the Enlightenment, and the contemporary nation-state. Literature provides a wisdom tradition to reflect on and engage with the international order.

Richard Ned Lebow Forbidden Fruit: Counterfactuals and International Relations (Princeton University Press, 2010): Counterfactuals are ‘what if?’ thought experiments that can probe causation and contingency. Lebow considers World War I, the Cold War, Mozart, and fictional alternative histories. He develops sophisticated protocols for evidence, theory-building, and theory-testing that will enrich social science, from archives and variables, to minimal rewrites and statistical inference.

Donella H. Meadows Thinking in Systems: A Primer (Chelsea Green, 2008): Meadows (1941-2001) was an influential environmental scientist and lead author on the Club of Rome’s Limits to Growth report (1972). Thinking in Systems is Meadows’ introduction to systems thinking, non-linearities, feedback, and leverage points. A way to build individual and societal resilience to complexity and global challenges.

Michael Scheuer Osama Bin Laden (Oxford University Press, 2011): Scheuer was head of the Central Intelligence Agency’s unit on Osama Bin Laden (1957-2011) and provides a corrective to earlier books. Scheuer depicts Bin Laden as a dynamic strategist with a deep knowledge of Muslim religious traditions, military logistics, and a long-term, dynamic vision for victory. Although Scheuer’s estimative assessments and specific conclusions will be debated, he also provides extensive end-notes, and a helpful guide to primary and secondary sources for further research.

Douglas Walton, Chris Reed, and Fabrizio Macagno Argumentation Schemes (Cambridge University Press, 2008): Argumentation schemes are processes of argument and inference which underlie human communication. Walton, Reed and Macagno provide an overview of how argumentation schemes inform fields from artificial intelligence to legal expert opinion. They classify and explain 96 different argumentation schemes and show how software tools like Rationale can be used to map out different inference structures.

Cynthia Connolly

Anything by MFK Fisher.

That’s my reading list!

Michelle Rae Anderson

I’m writing a semi-autobiography called The Miracle in July, and this finds me preoccupied with the elements of truth in fiction. I enjoy the intersection of truth and fantasy in following books:

Lidia Yuknavitch The Chronology of Water (2011): Lidia is a swimmer and a storyteller with a wild, self-serving past fueled by anger at helplessness. Beyond the usual “unbelievably shitty childhood” narrative found in most modern memoirs, in the Chronology of Water you’ll find a refreshing lack of apologies for the betrayal of secrets and an unusual writing style that mimics (to me) the little waves of breath in speech, as if the author is sitting there in the room reading the words to you.

Lidia Yuknavitch The Chronology of Water (2011): Lidia is a swimmer and a storyteller with a wild, self-serving past fueled by anger at helplessness. Beyond the usual “unbelievably shitty childhood” narrative found in most modern memoirs, in the Chronology of Water you’ll find a refreshing lack of apologies for the betrayal of secrets and an unusual writing style that mimics (to me) the little waves of breath in speech, as if the author is sitting there in the room reading the words to you.

Water-y loves, a dead baby, and a search for what “home” means are all critical parts to this story. Oh, and I’m pretty sure that is Lidia’s boob you see on the cover of the Chronology of Water. Pretty impressive for a middle-aged tit, I’d say.

Eric Kraft Herb N’ Lorna (AmazonEncore, 2010): I’ve been in love with this book since I discovered the first edition in my deeply religious grandmother’s car on the way to her memorial service back in the late 1980s. The story begins with a young man who, just as he is about to say a few loving words about his grandmother at her funeral, discovers that she and her husband spear-headed the discrete erotic, kinetic keepsake sculpture movement in the early 20th century.

Maybe it’s the coincidence in which I found the book and how the book begins, maybe it’s Kraft’s mesmerizing command of the well-played sentence, or maybe it’s that I’m just a sucker for a truly wonderful, touching love story…but this is the book that made me really believe in the power of writing a story that resonates, and inspired me to try my hand at it.

Robert Hough The Final Confession of Mabel Stark (Grove Press, 2004): This is the fictionalized, bittersweet memoir of the ferociously determined and beautiful Mabel Stark, a real lion tamer from the early days of Americana traveling circus performers. Working with huge, wild cats with the strength to maul tiny Mabel was nothing compared to the discrimination she faced from the Big Tent owners, and her five husbands could never take the place of her one true love: a white Bengal tiger named Rajah, a 500 lb. cat who considered her his mate.

Graphic bestiality scenes, shocking turns of plot and opportunity, and the ultimate price paid for love makes the Final Confession of Mabel Stark a riveting page turner. I mean, if you’re into that.

Steven Shaviro

Minister Faust The Alchemists of Kush (Kindle Edition; Narmer’s Palette, 2011) and Nnedi Okorafor Who Fears Death (DAW Trade, 2011): These two books are quite different from one another. But they are both brilliant works of Afrofuturist speculative fiction, linking past, present, and future, and moving between myth, magic, and grim social reality. Both novels confront visions of self-empowerment and self-healing with the horrors of genocide in South Sudan. The Alchemists of Kush is like a prose equivalent of some fusion between the cosmic jazz of Sun Ra and the gritty urban hiphop of the Wu-Tang Clan. Who Fears Death is a magic realist parable of future Africa, like a prose equivalent of Jill Scott channeling M’bilia Bell.

Ivor Southwood Non-Stop Inertia (Zer0 Books, 2011): This is a book about what it feels like to be a “precarious” worker, or a permanent temp worker, in the New Economy. Mixing cool analysis with telling anecodotal detail, Southwood dissects the ways that unemployment and even everyday life have been transformed into new forms of soul-shattering, mind-numbing labor, and how sheer economic constraint polices and disciplines us more effectively than oppressive social institutions were ever able to manage.

Evan Calder Williams Combined and Uneven Apocalypse: Salvagepunk, or Living Among the Ruins (Zer0 Books, 2011): Zombie attacks, or the stirrings of new collective urges. The Sex Pistols told us that we had No Future. Public Enemy told us that the apocalypse already happened. Several decades down the road, Williams describes how this catastrophic no-future is unevenly distributed. This book has striking insights, on nearly every page, about how the future has been systematically stolen from us. The sheer ferocity of Combined and Uneven Apocalypse matches that of the undead social and economic order we live in today.

China Mieville Embassytown (Del Rey, 2011): Last year, on my Summer Reading List, I recommended China Mieville’s then-new book Kraken. This year, Mieville makes the list again. He’s one of the finest writers of speculative fiction (or “weird fiction,” as he prefers to call it) alive today. But in Embassytown, Mieville surpasses himself — it’s one of the best things he’s ever done. In terms of genre, the book is a space opera. But it’s really about language, desire, and the nature of self-deception. Human beings share a planet with an alien race that only speaks the truth; but salvation for both species depends upon “our” ability to teach “them” how to lie.

China Mieville Embassytown (Del Rey, 2011): Last year, on my Summer Reading List, I recommended China Mieville’s then-new book Kraken. This year, Mieville makes the list again. He’s one of the finest writers of speculative fiction (or “weird fiction,” as he prefers to call it) alive today. But in Embassytown, Mieville surpasses himself — it’s one of the best things he’s ever done. In terms of genre, the book is a space opera. But it’s really about language, desire, and the nature of self-deception. Human beings share a planet with an alien race that only speaks the truth; but salvation for both species depends upon “our” ability to teach “them” how to lie.

K.W. Jeter The Kingdom of Shadows (Kindle Edition; Editions Herodiade, 2011): Jeter is one of our finest, and most underrated, writers of science fiction, fantasy, and horror. This is his first new book since his post-cyberpunk masterpiece Noir, published over a decade ago. I’ve just started reading The Kingdom of Shadows, so I’m not entirely sure yet what it is about. But it seems to involve Nazis, classical Hollywood, the uncanny reality of cinematic projections and other images, and strange metamorphoses of the skin.

Jeremy Dunham, Iain Hamilton Grant, and Sean Watson, Idealism: The History of a Philosophy (McGill Queens University Press, 2011): An introduction for a broad readership (but without sacrificing rigor and dense thought) to one of the most important, but also most reviled, trends in the history of Western philosophy. V. I. Lenin said it best: “Intelligent idealism is closer to intelligent materialism than is stupid materialism.”

Zizi Papacharissi

Richard Schechner Performance Theory (Routledge, 2003): Self-explanatorily, it is about performance theory — contains a favorite quote: “Performing is a public dreaming.” This is about drama and performativity in, and the drama and performativity of everyday life. Not specific to the internet, but I like to read this and imagine how it applies to play and performance online, and artificial agents and intelligence, including of course, robots.

Adrienne Russell Networked: A Contemporary History of News in Transition (Polity, 2011): I am a fan of slapping the word network in front of theories and concepts in order to remediate them (network society, networked publics, networked sociality, erm, networked self). It actually works 🙂 Networked is a great way to summarize a lot of things that have been going on in the field of journalism, including what Hermida (2010) refers to as ambient journalism. Really look forward to reading this.

David Gauntlett Making is Connecting (Polity, 2011): Pushing beyond ideas of convergence culture and cognitive surplus, and offering an informed and fresh explanation of how these processes come to be, and what they mean to people.

Joss Hands @ is for Activism: Dissent, Resistance and Rebellion in a Digital Culture (Pluto Press, 2011): Been thinking lately that, depending on context, sometimes online activism is more meaningful that offline mobilization. And sometimes not. Hoping that this book will help me think through this a bit more.

John Urry Cimate Change and Society (Polity, 2011): Intriguing, and a new way of thinking about things.

Also looking forward to Daniel Miller’s Tales from Facebook and Charlie Beckett’s book on Wikileaks and the threat of new news, both out from Polity later this Fall.

Erik Davis

For the last year, I have been part of the editorial team preparing a rather mammoth edited selection of Philip K. Dick’s largely unpublished Exegesis that should come out in late Fall from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. So most of my summer reading is a marathon swim through Dick’s dense, wonderful,  insightful, disturbing, boring, and deeply bizarre explorations of metaphysics, cybernetics, madness, mysticism, and God. It is an exhilarating and exhausting project to work on, but the material, for all its eccentricities, seems strangely timely, and I expect it may have the resonance of the Red Book when it appears (it even has lots of great diagrams and metaphysical doodles.) That said, the tome will only represent something like a tenth of the whole document, so this grail for the PKD nuts out there will remain half empty—which is probably just as well, since the desire for revelation is as revelatory as revelation itself, maybe more so.

insightful, disturbing, boring, and deeply bizarre explorations of metaphysics, cybernetics, madness, mysticism, and God. It is an exhilarating and exhausting project to work on, but the material, for all its eccentricities, seems strangely timely, and I expect it may have the resonance of the Red Book when it appears (it even has lots of great diagrams and metaphysical doodles.) That said, the tome will only represent something like a tenth of the whole document, so this grail for the PKD nuts out there will remain half empty—which is probably just as well, since the desire for revelation is as revelatory as revelation itself, maybe more so.

David Kaiser’s How the Hippies Saved Physics (W. W. Norton & Co., 2011) is a fabulous social and science history about the relationship between consciousness culture, philosophy and physics in the 1970s. He shows how the “big picture” questions initially stirred up by the confounding weirdness of quantum physics were lost in the pragmatic postwar world until a countercultural crew of freak physicists, quantum philosophers, meditators, paranormal aficionados, and speculative no-longer-materialists delved into the weirdest of the weird. Without a hint of snark, Kaiser tells the counter-cultural tales of figures like Jack Sarfatti, Fred Alan Wolf, and Nick Herbert, and books like Capra’s Tao of Physics (Shambhala, 1975). Science-wise, the heart of his story is Bell’s Theorem, whose deeply mindfucking argument for quantum nonlocality—that particles separated at birth can somehow “know” the state of their superposition twins through what is essentially some “faster than light” process or medium linking discrete spacetime reference points—became, for the hippies, a ground for a scientific understanding of all sorts of psi phenomena and hardcore mystical states. Along the way, though, they revived the philosophical issues surrounding quantum reality, which paradoxically are starting to bear practical fruit today, when Bell’s Theorem is a mainstay of quantum information science and esoteric cryptography.

Kaiser is a great science writer, not so much because he is good at describing quantum weirdness (he is, but so are other popular writers, including some of the folks—like Fred Alan Wolf—that he is writing about here). Kaiser is a great science writer because without sounding like the academic he is, his approach is deeply and successfully informed by historical and sociological methods of understanding how science happens: how ideas grow, propagate, and twist their way through changing historical scenes, especially scenes related to institutions, publications, networks of colleagues, and funding sources. And in the 1970s Bay Area, this productive social matrix got seriously strange, with alternative institutions, tech millionaires, and a visionary culture of interdisciplinary research infused with psychedelics, mysticism, and paranormal explorations. The quantum (meta)physical engagement with the nature of “consciousness” leads to some silly New Age science for sure (some of which we can blame on these folks) but it also asks us to really follow through the implications of quantum physics and to recognize how little we understand consciousness—and particularly the possibilities of “expanded consciousness.”

Along the lines of the technology of expanded consciousness, I have often gotten a lot out of Ivo Quartiroli’s posts on his indranet blog – intelligent, critical, but calmly expressed concerns about online culture and consciousness from the perspective of a programmer nerd who is also a hardcore meditator and intelligent spiritual seeker. His new book The Digitally Divided Self (Silens, 2011) is a kind of tech-nerd mystic’s version of Nicholas Carr’s The Shallows (W. W. Norton & Co., 2010), where some of the familiar (and not so familiar) concerns about the effect of the Internet on our brains, minds, bodies, and selves (including lots of research) are shot through with a bracing spiritual critique grounded in what one might call “post-rational” states of consciousness and experience. The philosophical language (around “reality” let’s say) is sometimes too simple, and he slips into some rote neo-Luddism at times, but this is very solid technology critique that takes the possibilities of spiritual practice very seriously—including the possibility that the training of attention through meditation may provide exactly what we need to dodge the dubious fate of becoming servo-mechanisms of the hive mind and manipulative networks of influence and distraction. Though it could have gone through another few rounds of editing, Ivo’s voice—concerned, compassionate, incisive, non-judgmental—is a unique and powerful one. Not a jeremiad, but a dharma combat.

Speaking of post-rational states of consciousness, I am incredibly happy to finally be reading Phil Baker’s Austin Osman Spare: The Life and Legend of London’s Lost Artist (Strange Attractor, 2010), the first book-length biography about the legendary occultist and fine artist, who was born in 1886 and died in the 50s. Spare is a fascinating fellow. As an artist, he transformed the aesthetic vibe of Beardsley-esque decadence into a unique and under-appreciated body of work (paintings, drawings, and amazing portraiture) that manages to be at once elegant, haunting, and deranged—the latter element at times reminiscent of Bacon. Moreover, Spare is arguably the most important—and almost certainly the most storied—British occultist after Crowley. His ideas and practices, highly idiosyncratic and deeply interfused with his remarkable artistic productions (especially his sigil magic), built a modernist bridge between the Edwardian culture of pseudo-traditionalist occult lore and a more Freudian, avant-garde, and psychologically radical embrace of the abject, the erotic, the unconscious—a bridge that makes him the godfather of chaos magic. Baker is a wonderful writer, careful, intelligent and tart. He also knows his London, and the Spare that emerges in his portrayal is very much an avatar of that unique and ancient town: humble Cockney beginnings, the bright years as a smoldering wunderkind, and then a long plunge into poverty, obscurity, and a deep weirdness that brought him in touch with Kenneth Grant, to whom we owe some of Spare’s legend. Spare emerges as an almost Blakean character, a visionary Londoner whose poverty could not keep the visions at bay.

Ashley Crawford

Joshua Cohen Witz (Dalkey Archive Press, 2010): Damn you Joshua Cohen. You’ve cost me dearly. Not only in time I couldn’t really afford (work suffered horrendously), but in the way you’ve twisted the world around me. Expending the energy to tackle an 827 page book takes a leap of faith to be sure. It also takes a few strong nudges. When those nudges come in a trinity one has to take a deep breath and dive in. The triumvirate, all discovered in a morning, started with an excerpt on Ben Marcus’ website, rapidly followed by noticing a rapturous blurb by Steve Erickson and then an intriguing interview by Blake Butler on 21cmagazine.com. Marcus, Erickson, and Butler are all heroes. They all wallow in language like words are the salt in the Dead Sea. But then a further google uncovered numerous comparisons with David Foster Wallace, Thomas Pynchon, Franz Kafka, and James Joyce. Ahem. And indeed, after several exhausting weeks, I can say that Joshua Cohen joins their ranks with enviable chutzpah. I am not one of the Affiliated, but trust me, you don’t need to be. Cohen essentially paints with words, creating vast canvases that embrace everything from surrealism to science fiction, from heart-wrenching heartbreak to heart-warming hilarity. Despite the sheer weirdness of structure, there is a clear-cut narrative here, albeit with a moment of cunnilingus that would make David Cronenberg blanch. Cohen has created an alternate universe richer than any in contemporary literature. Steve Erickson, in his blurb for the book, states that “the only question is whether Joshua Cohen’s novel is the Ark or the Flood.” My question back is, is it feasible that it is both?

Blake Butler There Is No Year: A Novel (Harper Perennial, 2011): It was perhaps inevitable that Blake Butler would do this. The seeds were already planted in his haunting novella Ever (Calamari Press, 2009) and his blistering, apocalyptic Scorch Atlas (Featherproof, 2009). There was already no doubt that he could write like an angel on bad hallucinogens. But there was no way one could have predicted the horrific tsunami that is There Is No Year – an experimental tour de force essentially unlike anything I have encountered in waking hours. Indeed I read it in a grueling two-day marathon that was not unlike those nightmares one has where one’s limbs are frozen and something unseen is pursuing you. Sleep paralysis is not unusual, but it is in broad daylight. In a blurb for Steve Erickson’s Days Between Stations (Simon & Schuster, 2005), Thomas Pynchon stated that Erickson “has that rare and luminous gift for reporting back from the nocturnal side of reality…” – it is an accolade that would have worked perfectly for Butler and There Is No Year. Indeed, reading this book is like being trapped in another person’s (deranged) psyche. It is, in essence, the story of a family; a father, a mother and a son who live in a melting world that has been assailed by a mysterious ‘light’. They remain unnamed, generic, which only adds to the sense of inevitability the book seems to exude. Upon finding a new home they also find a ‘copy family’. But that, it turns out, is the least of their problems. Indeed the copy family is the least original notion in a book of utter originality (Philip K. Dick utilised the same notion of simulacra or doppelganger in his 1954 story “The Father Thing” and it has appeared elsewhere), but Butler uses this trope to chilling affect. The ever trustworthy Ben Marcus claims that Butler has “sneaked up and drugged the American novel. What stumbles awake in the aftermath is feral and awesome in its power.” Feral is a good description here; Butler has gone off the leash, ignoring the rules of both grammar and sanity. Indeed, there is no year here, no month, no day, no hour. There is no distance, at least in the normal sense. But there is a narrative, in a feverish, nightmarish way. A number of comparisons have already been made to David Lynch (Butler admits to Lynch’s dense and macabre Inland Empire being something of an influence) and, inevitably, with both its “haunted house” theme and typographical mayhem, Mark Z. Danielewski’s brilliant House of Leaves (Pantheon, 2000). Both Lynch and Danielewski certainly hover somewhere in this Stygian night-scape, but There Is No Year stands on its own. Terrifying, ferocious, claustrophobic, a maelstrom of beautifully mangled words, a prose poem of paranoia. Butler has often complained of insomnia, but if these are his nightmares he may well be better off awake. I received my copy of There Is No Year a day after finishing Joshua Cohen’s equally brilliant epic Witz. My love-life, my social life, and my day job are in tatters, but Cohen and Butler (alongside such other Millennialists as Ben Marcus, Grace Krilanovich, Brian Evenson, Steve Erickson, Brian Conn, and others) more than prove that the Great American Novel is well and truly alive, albeit in wonderfully mutating forms.

David Foster Wallace The Pale King (Little, Brown, 2011): The publication of The Pale King has reignited the fascination that David Foster Wallace seems to inevitably ignite. His books, especially Infinite Jest, have inspired books in themselves and his suicide in 2008, at the age of 46, garnered not dissimilar coverage to that of Kurt Cobain. Indeed, DFW became the literary equivalent of a rock star. There was good reason for this. As anyone who has delved into Wallace’s disparate world(s) will attest, he had a voice like no other, regardless of whether he was working in obsessive reportage style or moments that border on pure surrealism. At times Wallace’s conceits border on the science-fictional – his first novel, Broom of the System (Penguin, 1986), is set in and alternate Ohio, where the primary landmark is a 100-square mile artificial desert of black sand, complete with imported scorpions and known as the Great Ohio Desert, or G.O.D., constructed to give its denizens a reminder of their pioneering roots. Similarly a Cleveland suburb has been re-built to emulate the outline of Jayne Mansfield’s body. In Infinite Jest (Little, Broan, 1990) he transforms the entire northeastern United States into an uninhabitable feral zone – an almost Ballardian virtual tropical jungle generated by dumping toxic waste in the area. In this instance, the U.S. has graciously given this land to Canada after ruining it for future civilizations. It is dubbed the Great Concavity to Americans and the Great Convexity to Canadians In this world North America envelops the United States, Canada and Mexico and is known as the Organization of North American Nations (O.N.A.N.). Corporate entities secure naming rights to each calendar year, eliminating traditional numerical designations, thus Jest is undertaken during The Year of the Depend Adult Undergarment (Y.D.A.U). And then there is one of the central tenets of Jest – the mysterious video-entertainment that is literally deadly. The Pale King eschews much of this other-worldly wizardry, but, Wallace being Wallace it’s not quite the real world either; IRS agents are issued new Social Security numbers, all beginning with the number 9, [a fiction] the IRS building facade is a gigantic 1040 form, picked out in terra-cotta tiling, and one of the agents has the ability to levitate when truly engrossed in his work. It’s not the masterpiece that was IJ, but to fans it is a sad and tantalizing read.

Grace Krilanovich The Orange Eats Creeps (Two Dollar Radio, 2010) Appearing almost simultaneously with Justin Cronin’s best-selling The Passage (Ballantine, 2010) comes yet another vampire book. Both feature blood-sucking ghouls and both feature young girls, and both have more  than a hint of the end of the world. And yet, they have absolutely nothing in common. One will entertain, the other will come close to performing a lobotomy on the reader. Grace Krilanovich’s The Orange Eats Creeps is a hyper-adrenalized journey through nocturnal spaces that reek with the stench of decay and mold. The journey screams with a post-punk adrenaline, like Nightwood on really bad acid. The hinted and occasionally overt sense of transgression blisters the page. The book features a perhaps overly orgasmic introduction by Steve Erickson who claims that The Orange Eats Creeps may well represent a “new literature”, a statement that cannot help but make one squirm. Rather than “new” per se, Krilanovitch has inherited streams of surrealist and grotesque elements that coil through the likes of Djuna Barnes, Comte de Lautréamont, George Bataille, Pierre Klossowski, Kathy Acker, and William Burroughs. To Erickson’s credit however, direct comparisons to such authors, beyond their clearly visceral use of language, would be meaningless. But Erickson does get it right when he describes Orange as “a vampire novel then as Celine would have written, with dashes of Burroughs and Tom Verlaine playing guitar in the background: hallucinatory, passionate, hardcore… a fiction of open wounds, like this savage rorshach of a book etched in scars of braille.” Krilanovich must have been forced to hold her ego in check given further comments from the likes of Shelly Jackson: “Like something you read on the underside of a freeway overpass in a fever dream,” she writes. “The Orange Eats Creeps is visionary, pervy, unhinged. It will mess you up.” And then the renowned Brian Evenson wades in with: “Reads like the foster child of Charles Burns’ Black Hole and William Burroughs’ Soft Machine (Grove Press, 1992). A deeply strange and deeply successful debut.” Burns’ Black Hole (Pantheon, 2008) is indeed an apt contemporary comparison. Set in a similarly bleak American outpost of ravaged suburbia, Black Hole is a searing portrait of adolescent alienation. Krilanovich goes one step further by inserting us firmly and uncomfortably inside her narrators often deranged skull, riding her seismic fluctuations of body temperature which seem to swirl dangerously from sexual overdrive to permafrost. Whether Krilanovich’s characters are literally vampires remains beside the point. Describing the ancestors of our protagonist, Krilanovich evokes figures that could be supernatural, but could as easily be simple environmental vandals: “Their contribution to the world lies in pockets of poisonous gas underground, that white swath beating at the door with the swollen fists of the unhappy dead; it wisps under the cabin window sash, animating that season’s psychos in a spark of electrified crackling fat that’s so irresistible they must drag their bones out the door…”

than a hint of the end of the world. And yet, they have absolutely nothing in common. One will entertain, the other will come close to performing a lobotomy on the reader. Grace Krilanovich’s The Orange Eats Creeps is a hyper-adrenalized journey through nocturnal spaces that reek with the stench of decay and mold. The journey screams with a post-punk adrenaline, like Nightwood on really bad acid. The hinted and occasionally overt sense of transgression blisters the page. The book features a perhaps overly orgasmic introduction by Steve Erickson who claims that The Orange Eats Creeps may well represent a “new literature”, a statement that cannot help but make one squirm. Rather than “new” per se, Krilanovitch has inherited streams of surrealist and grotesque elements that coil through the likes of Djuna Barnes, Comte de Lautréamont, George Bataille, Pierre Klossowski, Kathy Acker, and William Burroughs. To Erickson’s credit however, direct comparisons to such authors, beyond their clearly visceral use of language, would be meaningless. But Erickson does get it right when he describes Orange as “a vampire novel then as Celine would have written, with dashes of Burroughs and Tom Verlaine playing guitar in the background: hallucinatory, passionate, hardcore… a fiction of open wounds, like this savage rorshach of a book etched in scars of braille.” Krilanovich must have been forced to hold her ego in check given further comments from the likes of Shelly Jackson: “Like something you read on the underside of a freeway overpass in a fever dream,” she writes. “The Orange Eats Creeps is visionary, pervy, unhinged. It will mess you up.” And then the renowned Brian Evenson wades in with: “Reads like the foster child of Charles Burns’ Black Hole and William Burroughs’ Soft Machine (Grove Press, 1992). A deeply strange and deeply successful debut.” Burns’ Black Hole (Pantheon, 2008) is indeed an apt contemporary comparison. Set in a similarly bleak American outpost of ravaged suburbia, Black Hole is a searing portrait of adolescent alienation. Krilanovich goes one step further by inserting us firmly and uncomfortably inside her narrators often deranged skull, riding her seismic fluctuations of body temperature which seem to swirl dangerously from sexual overdrive to permafrost. Whether Krilanovich’s characters are literally vampires remains beside the point. Describing the ancestors of our protagonist, Krilanovich evokes figures that could be supernatural, but could as easily be simple environmental vandals: “Their contribution to the world lies in pockets of poisonous gas underground, that white swath beating at the door with the swollen fists of the unhappy dead; it wisps under the cabin window sash, animating that season’s psychos in a spark of electrified crackling fat that’s so irresistible they must drag their bones out the door…”

Patrick Barber

James McCommons Waiting on a Train: The Embattled Future of Passenger Rail Service—A Year Spent Riding across America (Chelsea Green, 2009): Necessary if you’re planning a train trip this summer. A good capsule history of trains in the US either way.

Jennifer Egan A Visit from the Goon Squad (Anchor, 2011): A thorny collection of interwoven stories that is well worth the trip.

Carlos Ruiz Zafón The Shadow of the Wind (Penguin, 2005).

Tom Rachman The Imperfectionists (Dial Press, 2011).

China Miéville The City and the City (Del Rey, 2010): Perfect for transit commutes, this book made my train ride to a faraway teaching job a really good time this spring.

Brian Tunney

For the past few years, I have been on an extensive Paul Theroux kick. And that continues, this summer, with The Happy Isles of Oceania: Paddling The Pacific (Hamish Hamilton, 1992), a travelogue written by Theroux throughout an 18-month journey that covered Meganesia, Melanesia, Polynesia and ends ultimately, in Hawaii.

For the past few years, I have been on an extensive Paul Theroux kick. And that continues, this summer, with The Happy Isles of Oceania: Paddling The Pacific (Hamish Hamilton, 1992), a travelogue written by Theroux throughout an 18-month journey that covered Meganesia, Melanesia, Polynesia and ends ultimately, in Hawaii.

The account was published in 1992, when I had just graduated high school and considered a trip to New York City from my suburban home in New Jersey a trek. But I’m not here to discuss relativism. I just thought New York was a faraway place (30 miles) and that my awesome bedroom in my parent’s suburban home was safer and all that I had ever known.

I guess my distant interest with the author started early in college, when I was forced to read his first travelogue, The Great Railway Bazaar. At the time, book reading wasn’t really what I wanted to do, nor was travel by train through Europe, into Asia, and back again over a four-month journey, as Theroux does in the book. But I forced myself through the book, correctly identified the points my professor wanted me to and didn’t look back.

A decade later, I re-discovered the same book in a box stowed away since college, and decided to reread it. Instantly, after gaining a somewhat nominal level of experience with travel through distant and unknown (to me) parts of the world, namely Connecticut and Thailand, Theroux’s writing grew on me. He had a knack for entering into a new part of the world and not passing a subjective judgment after two hours in the new location. Instead, Theroux entered, observed, questioned and conjectured until he simply decided to move onto the next place. His approach was anthropological without adhering to structure, engaging, and altogether the next best thing to actually running around the world by train for a year at a time.

In 2008, Theroux returned to The Great Railway Bazaar with Ghost Train to the Eastern Star, a re-tracing of his journey some twenty years later. And although he had gained some years, he goes out of his way to traverse the same path, exploring the changes in government, culture and the land’s greater history along the way. (Not surprisingly, much had changed, including the fall of Communism in Eastern Europe, the post 9/11 treatment of Arab countries and a worldwide energy and economic crisis.) He also goes out of his way to integrate regional literature and past interpretations of the lands he visits (Rimbaud is a frequent reference, but so is Arthur C. Clarke and a host of other influential writers along the way) into the lands he visits.

After Ghost Train, I craved more, and I turned to Theroux to teach me about the world’s greater workings, including Africa (Dark Star Safari) and China (Riding the Iron Rooster). And now I find myself 90-pages into his paddle boat explorations of New Zealand, Australia, and lands I haven’t yet reached in the book. So far, he’s attempted to tackle racism, alcoholism on a societal scale, the killing of animals, and wind in a small paddle boat along the Australian coast. He also just bought a gun in case he’s overrun by wild pigs in the outback.

I read, most days, on a train to and from work, knowing the exact outcome of my day sometimes before it begins. Paul Theroux’s writing is my daily escape from the norm, a window into an once unknown world, and an attempt to reconcile all of the problems of the world by talking to each person he meets one on one and having a beer with them at the end of the day.

I only hope that one day, Paul Theroux stands next to me on the train underneath the Hudson River and wants to talk.

Michael Schandorf

This summer I’m reading about how we enact and comprehend space and time, how our spaces affect our thinking and interaction, and how time relates to cognition. And I’m starting with Carrie Noland’s Agency and Embodiment (Harvard University Press, 2009). Noland is a professor of French and comparative literature at the University of California, Irvine, with a background in dance. The combination has led her to the study of body movement and the enactment of culture in a broad sense. In Agency and Embodiment, she explores a range of theoretical positions, including Marcel Mauss’s early sociological and anthropological theories, the phenomenology of digital art, and post-modern/post-colonial performative agency. The breadth of this contextualization of embodiment promises a rich perspective.

Next up, Erin Manning’s Relationscapes (MIT Press, 2009) covers loosely similar territory. Manning is the Director of Concordia University’s Sense Lab in Montreal, the scope of which is reflected in her book’s subtitle: Movement, Art, Philosophy. Manning offers a theory of movement that connects incipient emotion to the production of language in a theory of “prearticulation” that suggests David McNeill’s studies of gesture in linguistics and cognitive psychology, but with a wider scope that encompasses aesthetic production.

From “prearticulation” to Premediation (Palgrave, 2010)… A decade ago, Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin’s Remediation (MIT Press, 2000) brought a crucially  important rigor to the theorization of media studies. Grusin’s latest, Premediation, is an update and expansion of the theory of remediation that examines the changes in media communication and cultural tenor following the September 11th attacks. In essence, Grusin argues that the blinding pace of information transmission, combined with a general cultural mood of trauma and fear, has shifted our relationship to time from the present focus of mass media communications in the late 20th century to anticipation of the immediate future that dominate much of today’s mass media, especially on cable news. The processes of premediation, Grusin argues, are an attempt to protect the social and cultural psyche from the terror of unforeseen shocks like those of 9/11.

important rigor to the theorization of media studies. Grusin’s latest, Premediation, is an update and expansion of the theory of remediation that examines the changes in media communication and cultural tenor following the September 11th attacks. In essence, Grusin argues that the blinding pace of information transmission, combined with a general cultural mood of trauma and fear, has shifted our relationship to time from the present focus of mass media communications in the late 20th century to anticipation of the immediate future that dominate much of today’s mass media, especially on cable news. The processes of premediation, Grusin argues, are an attempt to protect the social and cultural psyche from the terror of unforeseen shocks like those of 9/11.

Moving on from largely visual and mediated interactions, Brandon LaBelle’s Acoustic Territories (Continuum, 2010) explores the nature of space, particularly contemporary urban spaces, in terms of sound cultures and the audial embodiment of our lived spaces. LaBelle is an artist and writer teaching at the National Academy of Arts in Bergen, Norway, and Acoustic Territories appears to be an expansion of the themes in his previous book, Background Noise (Continuum, 2006), which focused more exclusively on consciously aesthetic production. Sound is a crucial sense for most of us for purposes of social identification, but the role hearing places in our conceptualization and enactment of space and time is largely taken for granted. I’m looking forward to digging into LaBelle’s treatment.

Finally, a book whose connection to these themes is a bit more tenuous – but one I’m really excited about – is R. Douglas Fields’ The Other Brain (Simon & Schuster, 2010). Neurons and their physiology have been the focus of brain research and the basis of cognitive theories since their discovery and early description. But neurons only make up about 15% of the brain. Most of the rest of that mass is glial cells, which have historically been brushed aside as ‘helper cells’. Fields reviews important recent research on glial cells showing that they do far more than “help”: glial cells organize and structure neurons and modulate both neuronal transmission and synaptic activity. They communicate both with neurotransmitters and globally with broader chemical and bioelectrical signals, making them far more important to the processes of cognition than has been previously acknowledged. Thinking is more than synapses as mind is more than thinking.

Peter Lunenfeld

Summer is when I catch up with fiction and read a few things that might touch on work when it kicks back into gear in the fall. There’s an old joke that professors will never admit to reading something, they are always “rereading.” But I’m fully willing to admit that this is the summer I’ve decided to read David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest for the first time. I’ve never carved the time and attention out for his 1K+ page masterpiece. Now I am.

I’ve been writing for The Believer and decided to work my way through the novels of its three co-editors. A few years back I read Heidi Julavits’ third book, Uses of Enchantment (Anchor, 2008), a fantastic novel about young women and the myth and mystery of memory, and I now plan to read in reverse, tackling her second book, The Effect of Living Backwards (Berkley Trade, 2004). I recently went to the Hammer Museum in LA where Heidi and Vendela Vida both read. Vendela’s was from The Lovers (Ecco, 2010), and the excerpt she chose was so poignant and evocative of place and time (Florence, a quarter of a century ago) that her novel, along with its predecessor, Let the Northern Lights Erase Your Name (Harper Perennial, 2008), are on my list. To round off my Believer kick, I’m also planning to read third co-editor Ed Park’s Personal Days (Random House, 2008), a novel of contemporary office life.

I consumed the uneven Steig Larsson trilogy, and continue to explore Scandinavian crime fiction. So this summer, I’ll probably read some or all of Jo Nesbø’s Oslo-based noir mysteries, including the neo-Nazi themed The Redbreast (Harper, 2008), the heist story Nemesis (Harper, 2009), and the serial killer-driven The Devil’s Star (Harper, 2011 ; though sexual-serial killings was the lamest part of the Girl With that Tattoo who Lit Stuff on Fire and Kicked Nests). On the other hand, I’ve never read mysteries by anybody with an ø in their name, so perhaps that will make up for it.

In the fall, I’ll continue working on a series of essays about Los Angeles and its history, and one of the books I’m looking forward to reading for this project is Spencer Kansa‘s Wormwood Star: The Magickal Life of Marjorie Cameron (Mandrake, 2011). Cameron was a fascinating figure, the lead actress in Kenneth Anger’s film, Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome, and the consort of the endlessly fascinating Jack Parsons, rocket pioneer, co-founder of the Jet Propulsion Lab, nemesis of L. Ron Hubbard, and Satanist. Parsons and Cameron tried to give birth to a Moon Child, but that’s a long story…

Finally, through the summer I’ll be playing around with an app that Chandler McWilliams developed for my new book, The Secret War Between Downloading & Uploading (MIT Press, 2011). The app is called GenText, takes the last chapter of the book – a stand-alone history of the computer as culture machines titled “Generations” – and renders it accessible at three levels — abstract, page, and full section — with a dynamic interaction between the levels that literalizes the metaphor of “zooming” into a text. The book’s companion website, points you to it as well as other e-pub goodies.

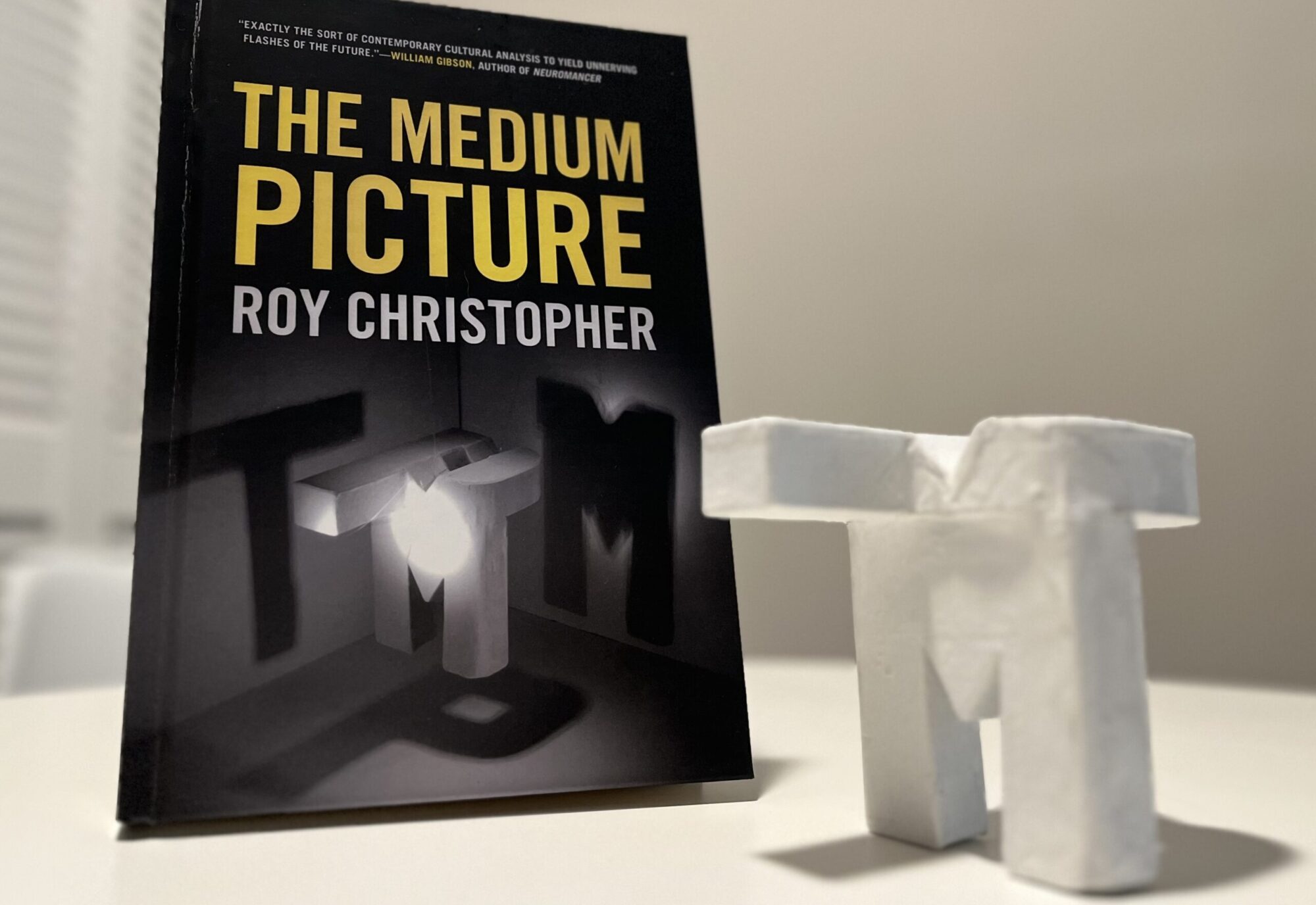

Roy Christopher

I’m currently working on my book, The Medium Picture (for Zer0 Books), so most of my reading lately has been related to the writing. That means essential texts from Marshall McLuhan, Walter Ong, Neil Postman, Howard Rheingold, Doug Rushkoff, Paul Levinson, Steven Johnson, Ted Nelson, Lev Manovich, Kate Hayles, Peter Lunenfeld, David Weinberger, Stewart Brand, Jay David Bolter, Janet Murray, McKenzie Wark, and others — all of which lead me to newer stuff like…

James Gleick The Information (Pantheon, 2011): James Gleick always brings the goods, and The Information is no exception. This is a definitive history of the info-saturated now. From Babbage, Shannon, and Turing to Gödel, Dawkins, and Hofstadter, Gleick traces the evolution of information theory from the antediluvian alphabet and the incalculable incomplete to the memes and machines of the post-flood. I’m admittedly biased (Gleick’s Chaos quite literally changed my life’s path), but this is Pulitzer-level research and writing. The Information is easily the book of the year.

James Gleick The Information (Pantheon, 2011): James Gleick always brings the goods, and The Information is no exception. This is a definitive history of the info-saturated now. From Babbage, Shannon, and Turing to Gödel, Dawkins, and Hofstadter, Gleick traces the evolution of information theory from the antediluvian alphabet and the incalculable incomplete to the memes and machines of the post-flood. I’m admittedly biased (Gleick’s Chaos quite literally changed my life’s path), but this is Pulitzer-level research and writing. The Information is easily the book of the year.

Peter Lunenfeld The Secret War Between Downloading & Uploading (MIT Press, 2011): The subtitle of Peter Lunenfeld’s newest book is “Tales of the Computer as Culture Machine.” Lunenfeld employs downloading and uploading for cultural consumption and production respectively. His metaphors are apt, and astutely frame the computer’s role in our current culture. This is an important little book that should not be ignored.

Adam Bly Science is Culture (Harper Perennial, 2010): I love magazines, and one of my favorites was Seed. Adam Bly is/was their editor (they’re online-only now), and one of my favorite parts of Seed was the Seed Salon, in which two scientific or literary luminaries — whose interests are often unexpectedly juxtaposed — discuss a pressing science issue. Well, Bly’s new book compiles all of the Seed Salon sessions in one place. It includes such pairings as David Byrne and Daniel Levitin, Albert-László Barabási and James Fowler, Jonathon Lethem and Janna Levin, Benoit Mandlebrot and Paola Antonelli, Will Self and Spencer Wells, Jill Tarter and Will Wright, Tom Wolfe and Michael Gazzaniga, and Robert Stickgold and Michel Gondry, among many others. Unexpected things emerge when pairs of minds like these come together.

Elizabeth Parthenia Shea How the Gene Got Its Groove (SUNY Press, 2008): In How the gene Got Its Groove, Shea argues that the gene is no more than a figure of speech, a trope, a metonymy for a unit of life-stuff that may or may not exist. It’s an intriguing romp through lingustic strategy, the tenuousness of language, and indeed the rhetorical nature of science itself.

McKenzie Wark The Beach Beneath the Street: The Everyday Life and Glorious Times of the Situationist International (Verso, 2011): Ken Wark‘s been writing around and adjacent to the Situationists for years. It’s awesome to see him finally dive into their strange land in earnest. There are many texts on Guy Debord and the Situationists, but few dig as deep or get their work the way Ken Wark does. As a rare bonus, the hardback comes with a fold-out dust cover with a graphic essay composed and drawn by Kevin C. Pyle based on selections from Wark’s text.

Steven Shaviro Post-Cinematic Affect (Zer0 Books, 2010): I’ve been meaning to write about Steven Shaviro‘s new book since I got it last year. It’s a fascinating exploration of four cinematic artifacts: Grace Jones’ “Corporate Cannibal” video, and the films Boarding Gate (2007), Gamer (2009), and Southland Tales (2006), the latter of which is one of my recent favorites. The book’s title comes from Shaviro’s central claim: that so-called “new media” hasn’t killed but transformed filmmaking, and since media artifacts as such are “machines for generating affect,” these four works represent perfect occasions to discuss our current state of post-cinematic affect.

————

Well, that’s what we’re reading this summer. Time to get to it.

[Pictured above: Lily checking out The Hitch. photo by royc.]

John Cage: Music, Philosophy, and Intention, 1933-1950 edited by David W. Patterson (Routlege, 2002) is the only book out that concentrates on Cage’s early career, and it includes contributions from an international collection of art and musicology scholars. Insights into his early years are rare, and this book is full of them, insisting correctly that revisiting his early years proffers up a deeper understanding of his later work and philosophy. For instance, his time in my adopted home of Seattle marked an oft overlooked turning point. Cage lamented the move to an increasingly urban society until he learned to listen to it — as music. This transition was paramount to his abandoning traditional composition, his shift to a percussive composition style, and his move squarely into the avant-garde.

John Cage: Music, Philosophy, and Intention, 1933-1950 edited by David W. Patterson (Routlege, 2002) is the only book out that concentrates on Cage’s early career, and it includes contributions from an international collection of art and musicology scholars. Insights into his early years are rare, and this book is full of them, insisting correctly that revisiting his early years proffers up a deeper understanding of his later work and philosophy. For instance, his time in my adopted home of Seattle marked an oft overlooked turning point. Cage lamented the move to an increasingly urban society until he learned to listen to it — as music. This transition was paramount to his abandoning traditional composition, his shift to a percussive composition style, and his move squarely into the avant-garde. Though his work was arguably as groundbreaking and influential as Cage’s, Iannis Xenakis is a lesser-known and written-about composer. Like Cage, he used strange maths in his compositions. His own book, Formalized Music: Thought and Mathematics in Composition (Pendragon, 1971), set out to, well, formalize his mathematical approach, and it illuminates much of his work in the process. In Xenakis: His Life in Music (Routledge, 2011), James Harley sets out to do the same. A composer himself, Harley studied with Xenakis and completed two compositions on the UPIC (Unité Polygogique Informatique de CEMAMu), Xenakis’ computer system “based on a graphic-design approach to synthesis” (p. x). This background obviously informs his writing, but his aim is to give the reader an entry point into Xenakis’ complex techniques and compositions, as well as his intellectual history and his contributions outside of music. I can’t claim to know if he succeeded — math and music both look like alien linguistics to me — but in its updated paperback from, Xenakis should help spread the word about Xenakis’ work and help secure his place in the history of experimental music.

Though his work was arguably as groundbreaking and influential as Cage’s, Iannis Xenakis is a lesser-known and written-about composer. Like Cage, he used strange maths in his compositions. His own book, Formalized Music: Thought and Mathematics in Composition (Pendragon, 1971), set out to, well, formalize his mathematical approach, and it illuminates much of his work in the process. In Xenakis: His Life in Music (Routledge, 2011), James Harley sets out to do the same. A composer himself, Harley studied with Xenakis and completed two compositions on the UPIC (Unité Polygogique Informatique de CEMAMu), Xenakis’ computer system “based on a graphic-design approach to synthesis” (p. x). This background obviously informs his writing, but his aim is to give the reader an entry point into Xenakis’ complex techniques and compositions, as well as his intellectual history and his contributions outside of music. I can’t claim to know if he succeeded — math and music both look like alien linguistics to me — but in its updated paperback from, Xenakis should help spread the word about Xenakis’ work and help secure his place in the history of experimental music.

As usual, the Summer Reading List is the time of year when I ask a bunch of my bookish friends what they’re reading. It’s always a good time, and this year we have newcomers and old friends

As usual, the Summer Reading List is the time of year when I ask a bunch of my bookish friends what they’re reading. It’s always a good time, and this year we have newcomers and old friends

than a hint of the end of the world. And yet, they have absolutely nothing in common. One will entertain, the other will come close to performing a lobotomy on the reader. Grace Krilanovich’s The Orange Eats Creeps is a hyper-adrenalized journey through nocturnal spaces that reek with the stench of decay and mold. The journey screams with a post-punk adrenaline, like Nightwood on really bad acid. The hinted and occasionally overt sense of transgression blisters the page. The book features a perhaps overly orgasmic introduction by Steve Erickson who claims that The Orange Eats Creeps may well represent a “new literature”, a statement that cannot help but make one squirm. Rather than “new” per se, Krilanovitch has inherited streams of surrealist and grotesque elements that coil through the likes of Djuna Barnes, Comte de Lautréamont, George Bataille, Pierre Klossowski, Kathy Acker, and William Burroughs. To Erickson’s credit however, direct comparisons to such authors, beyond their clearly visceral use of language, would be meaningless. But Erickson does get it right when he describes Orange as “a vampire novel then as Celine would have written, with dashes of Burroughs and Tom Verlaine playing guitar in the background: hallucinatory, passionate, hardcore… a fiction of open wounds, like this savage rorshach of a book etched in scars of braille.” Krilanovich must have been forced to hold her ego in check given further comments from the likes of Shelly Jackson: “Like something you read on the underside of a freeway overpass in a fever dream,” she writes. “The Orange Eats Creeps is visionary, pervy, unhinged. It will mess you up.” And then the renowned Brian Evenson wades in with: “Reads like the foster child of Charles Burns’ Black Hole and William Burroughs’

than a hint of the end of the world. And yet, they have absolutely nothing in common. One will entertain, the other will come close to performing a lobotomy on the reader. Grace Krilanovich’s The Orange Eats Creeps is a hyper-adrenalized journey through nocturnal spaces that reek with the stench of decay and mold. The journey screams with a post-punk adrenaline, like Nightwood on really bad acid. The hinted and occasionally overt sense of transgression blisters the page. The book features a perhaps overly orgasmic introduction by Steve Erickson who claims that The Orange Eats Creeps may well represent a “new literature”, a statement that cannot help but make one squirm. Rather than “new” per se, Krilanovitch has inherited streams of surrealist and grotesque elements that coil through the likes of Djuna Barnes, Comte de Lautréamont, George Bataille, Pierre Klossowski, Kathy Acker, and William Burroughs. To Erickson’s credit however, direct comparisons to such authors, beyond their clearly visceral use of language, would be meaningless. But Erickson does get it right when he describes Orange as “a vampire novel then as Celine would have written, with dashes of Burroughs and Tom Verlaine playing guitar in the background: hallucinatory, passionate, hardcore… a fiction of open wounds, like this savage rorshach of a book etched in scars of braille.” Krilanovich must have been forced to hold her ego in check given further comments from the likes of Shelly Jackson: “Like something you read on the underside of a freeway overpass in a fever dream,” she writes. “The Orange Eats Creeps is visionary, pervy, unhinged. It will mess you up.” And then the renowned Brian Evenson wades in with: “Reads like the foster child of Charles Burns’ Black Hole and William Burroughs’

Even though

Even though

Few actors have had careers anywhere near as diverse and dynamic as Nicolas Cage. A member of the Royal Coppola Family, Cage has been in everything from goofy teen comedies like Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982) to mind-blowing, block-busting adventures like National Treasure (2004). His acting agility is abetted by his willingness and ability to take on challenging roles that other thespians of his caliber wouldn’t think of accepting — and pulling them off without dumbing them down. As

Few actors have had careers anywhere near as diverse and dynamic as Nicolas Cage. A member of the Royal Coppola Family, Cage has been in everything from goofy teen comedies like Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982) to mind-blowing, block-busting adventures like National Treasure (2004). His acting agility is abetted by his willingness and ability to take on challenging roles that other thespians of his caliber wouldn’t think of accepting — and pulling them off without dumbing them down. As

In the similarly quirky Wild at Heart (the plot of which I always confuse with True Romance, perhaps because of their similarly Westbound plots and blonde love interests), Cage would almost reprise this role. He was to all but abandon this kind of character later in his career, save maybe Adaptation (2002) and, our last stop, Matchstick Men (2003).

In the similarly quirky Wild at Heart (the plot of which I always confuse with True Romance, perhaps because of their similarly Westbound plots and blonde love interests), Cage would almost reprise this role. He was to all but abandon this kind of character later in his career, save maybe Adaptation (2002) and, our last stop, Matchstick Men (2003). What happened to the casting director on this star-studded screen scorcher? Fired for awesomeness? How about the screenwriter or the director?

What happened to the casting director on this star-studded screen scorcher? Fired for awesomeness? How about the screenwriter or the director?

![Eclectic Method at Austin Music Hall [photo by Justin Bolognino]](http://roychristopher.com/wp-content/uploads/eclectic-method-sxsw.jpg)

The Action Books come with durable rubbery covers and muted but colorful to-do lists. The back of every page is ruled with dots, which are subtly guiding without being as intrusive as lines or as restrictive as grids. They’re perfect for notes, sketches, diagrams, flowcharts, mindmaps, or any combination thereof. My

The Action Books come with durable rubbery covers and muted but colorful to-do lists. The back of every page is ruled with dots, which are subtly guiding without being as intrusive as lines or as restrictive as grids. They’re perfect for notes, sketches, diagrams, flowcharts, mindmaps, or any combination thereof. My